COA 2022 PBM Dirty Tricks Exposé Report

Executive Summary

There is growing awareness of the problems and pitfalls with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) in the United States health care system. Contracted by plan sponsors (including government programs, self-insured employers, and insurance companies) to negotiate on their behalf with pharmaceutical companies, these “middlemen” corporations have quietly become an unavoidable part of our nation’s health care system.

Today, fewer than five PBMs control more than 80 percent of drug benefits for over 260 million Americans, which includes the power to negotiate drug costs, what drugs will be included on plan formularies, and how those drugs are dispensed. Oftentimes, patients are required to receive drugs through PBM-owned or affiliated specialty and mail-order pharmacies and suffer serious, sometimes dangerous, and even deadly, impacts of their abuses as a result of medication delays and denials.

However, while the role PBMs play in the U.S. health care system is complex and under scrutiny by both federal and state policymakers and the public, it is increasingly becoming clear that PBMs make up an oligopoly of rich, vertically integrated conglomerates that routinely prey on health care practices, providers, and their patients. PBMs have done this by overwhelmingly abusing their responsibility to protect Americans from this country’s drug pricing crisis, instead of exploiting the opacity throughout the nation’s drug supply chain to enrich themselves.

Unfortunately, their impact is only becoming more pronounced, especially in the world of cancer care. More and more cancer medications are coming out in oral formulations, resulting in a shift away from the medical benefit and into the pharmacy benefit. And because cancer medications are among the most expensive out there, they are very attractive to PBMs because they yield higher rebates, higher “DIR fees,” and other pricing gimmicks that yield substantial profits.

Through vertical integration and sheer market power, PBMs have also been able to creep into other areas of our health care system, such as injectable biosimilars and intravenous chemotherapies. Not only can PBMs leverage these products for steep originator drug rebates (thereby stifling the biosimilar industry for their own gain), but PBMs have also begun to institute policies such as mandatory “white bagging” to take the in-office administration out of the hands of patients’ oncologists.

The purpose of this exposé is to reveal and explain PBMs’ advantage and leverage by providing transparency where now there is total darkness, and by delving into the many ways that PBMs have abused their power. This report comprehensively explores and documents the myriad of PBM abuses, and their impact on patient care – focusing especially on cancer care. It explores how the recent levels of consolidation among PBMs and health insurers are adversely impacting cancer care, fueling drug costs, all while allowing for massive profits for PBMs and health insurance companies. Examining the most pervasive and abusive PBM tactics, each section highlights the adverse impact of PBMs on patients, healthcare payers (including Medicare, Medicaid, employers, and taxpayers), and providers, while also detailing potential solutions.

Each day that goes by, physicians, practices, and most importantly, patients become increasingly powerless because of horizonal PBM consolidation and vertical integration with insurers. The result is a system designed for patients to receive inferior treatment, while paying more out-of-pocket for their medications.

The time for sitting back and hoping for PBMs to become good faith actors is over. It is time for action to stop PBM abuses once and for all, and this exposé provides a road map for tackling them one dirty PBM trick at a time.

Introduction

In the eyes of many Americans, the problem with drug pricing is caused by unscrupulous pharmaceutical manufacturers who have increased drug prices over the last two decades with reckless abandon. This has been exemplified by a handful of highly visible bad actors, such as “pharma-bro” Martin Shkreli or Nostrum Pharmaceuticals founder, Nirmal Muyle, who rightfully captured the public’s attention, but wrongfully over-simplified the causes of our nation’s drug pricing issues.

Far more dangerous and insidious actors have quietly grown to dominate the nation’s pharmaceutical industry and drive high drug prices through the secretive pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) industry. Ironically, in the country’s attempt to rein in ruthless operators like Shkreli and Muyle, we ended up inadvertently creating the PBM problem that now plagues us. Expanding the role of PBMs, first from simple processors of pharmacy claims to middlemen more actively managing the prescription benefit initially made some sense. Clients – employers, unions, state governments, and other payers of medical care – did not have the expertise to manage complex drug benefits. Thus, they could hire a PBM to administer their prescription benefit, which would include simplifying and streamlining a complicated drug supply chain, designing formularies to exclude wasteful drugs, using their size and leverage to negotiate better discounts from pharmaceutical manufacturers, and managing pharmacy networks to create better outcomes for patients.

However, as this exposé on PBM business tactics, dirty tricks, and their negative impacts will detail, what seemed like a good idea “on paper” has not come to fruition. Instead, the nation’s largest PBMs have capitalized on the complexity of the drug supply chain and used the secrecy in which they operate to hide the true cost of drugs. And rather than eliminate the costly arbitrage within the supply chain, PBMs co-opted and embraced it, exacerbating the very problems of high drug prices that they were originally hired to control. They saw the financial windfall that would come through vertical integration and bought or set up their own mail-order and specialty pharmacies, steering patients away from independent community pharmacies and medical practices to their wholly-owned or affiliated pharmacy facilities where they could retain the inflated prices (and profits) they themselves were responsible for creating.

The perverse result is that PBMs have abandoned their most sacrosanct function of protecting their clients from high cost or low benefit drugs, instead letting higher priced drugs “buy” their way onto their clients’ formularies via rebates that the PBMs mostly retain. They then set up affiliated rebate aggregator entities to further obfuscate the flow of pharmaceutical manufacturer dollars, retaining a larger portion of their clients’ rebates, and leaving patients on high deductible plans exposed to drugs with exploitative list prices. The result is that patients pay more for their drugs off of artificially inflated list prices and the PBM clients have higher prescription drug costs.

The PBM’s purpose in the drug supply chain was to “police” the system. Had the largest PBMs not been lured in by the immense profit potential borne out of the complete opacity of drug costs, a PBM’s greatest asset would have been trust – trust from payers and providers that they were tirelessly working to protect the American public from high drug prices. However, this unfortunately did not come to pass. Instead, the PBM’s greatest advantage has become the almost total opacity of the U.S. drug supply chain and a lack of understanding among employers, unions, state governments, and American taxpayers of how most PBMs have chosen to abuse it.

The purpose of this exposé is to reveal and explain the PBM advantage by providing transparency where now there is total darkness and delving into the many ways that PBMs have abused their power to become “crooked cops.” Throughout this exposé, we comprehensively explore and document the myriad of PBM abuses, and their impact on patient care – focusing especially on cancer care. Finally, we explore how the recent levels of consolidation among PBMs and health insurers is adversely impacting cancer care, fueling drug costs, while allowing for massive profits for PBM and health insurance companies. We have thoroughly examined and detailed the most pervasive and abusive PBM tactics, in each section highlighting their adverse impact on patients, health care payers (including Medicare, Medicaid, employers and taxpayers), and providers.

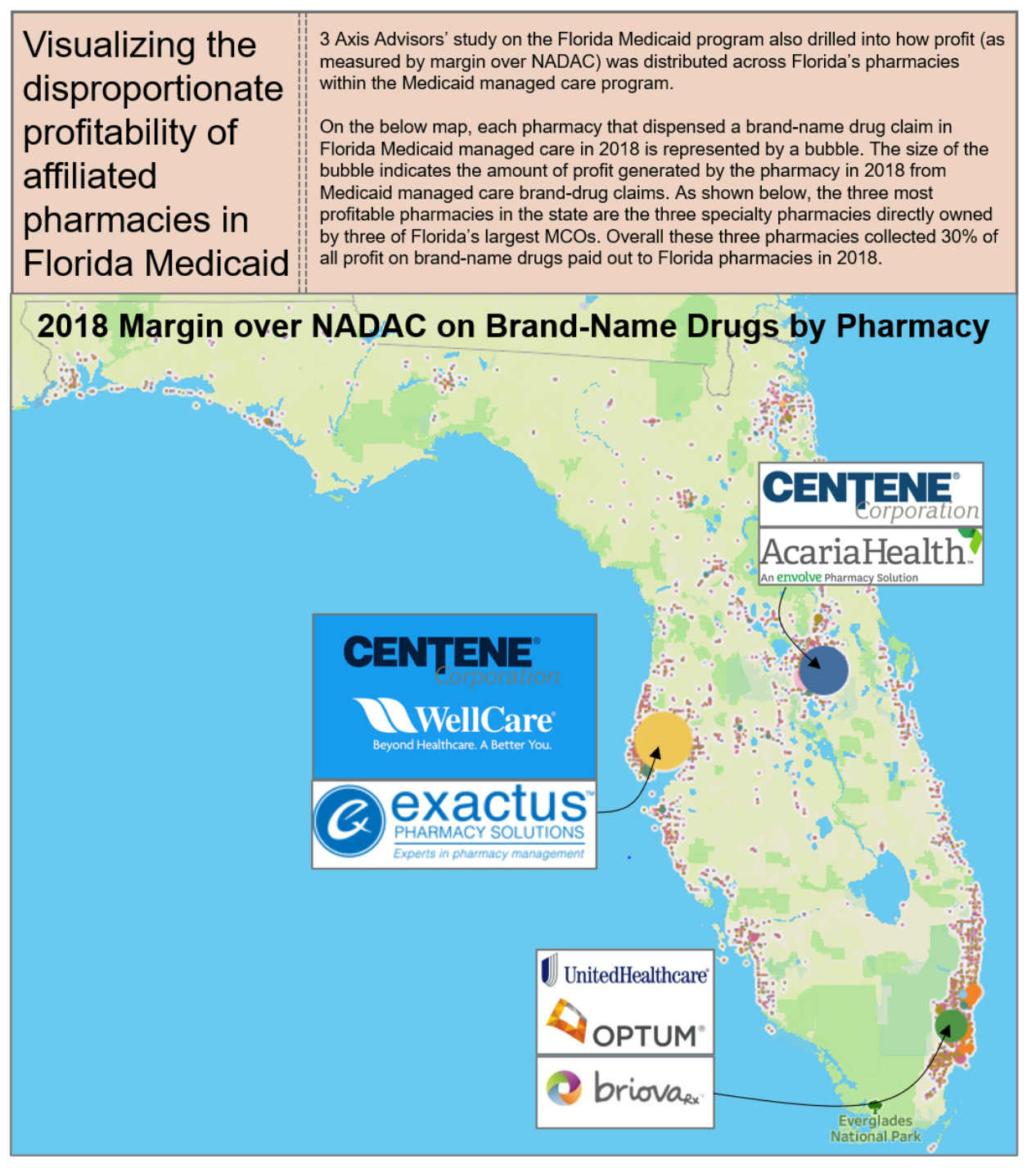

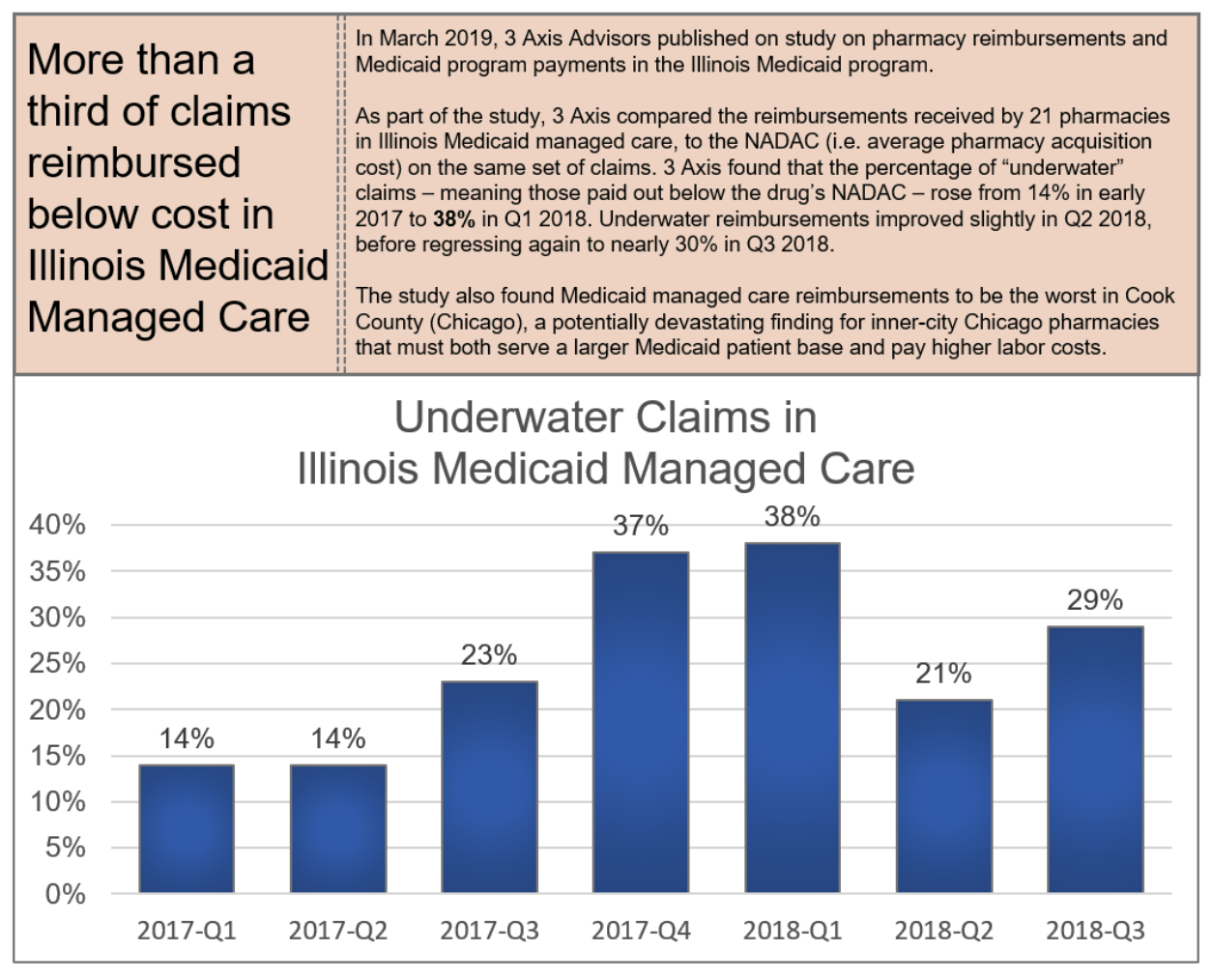

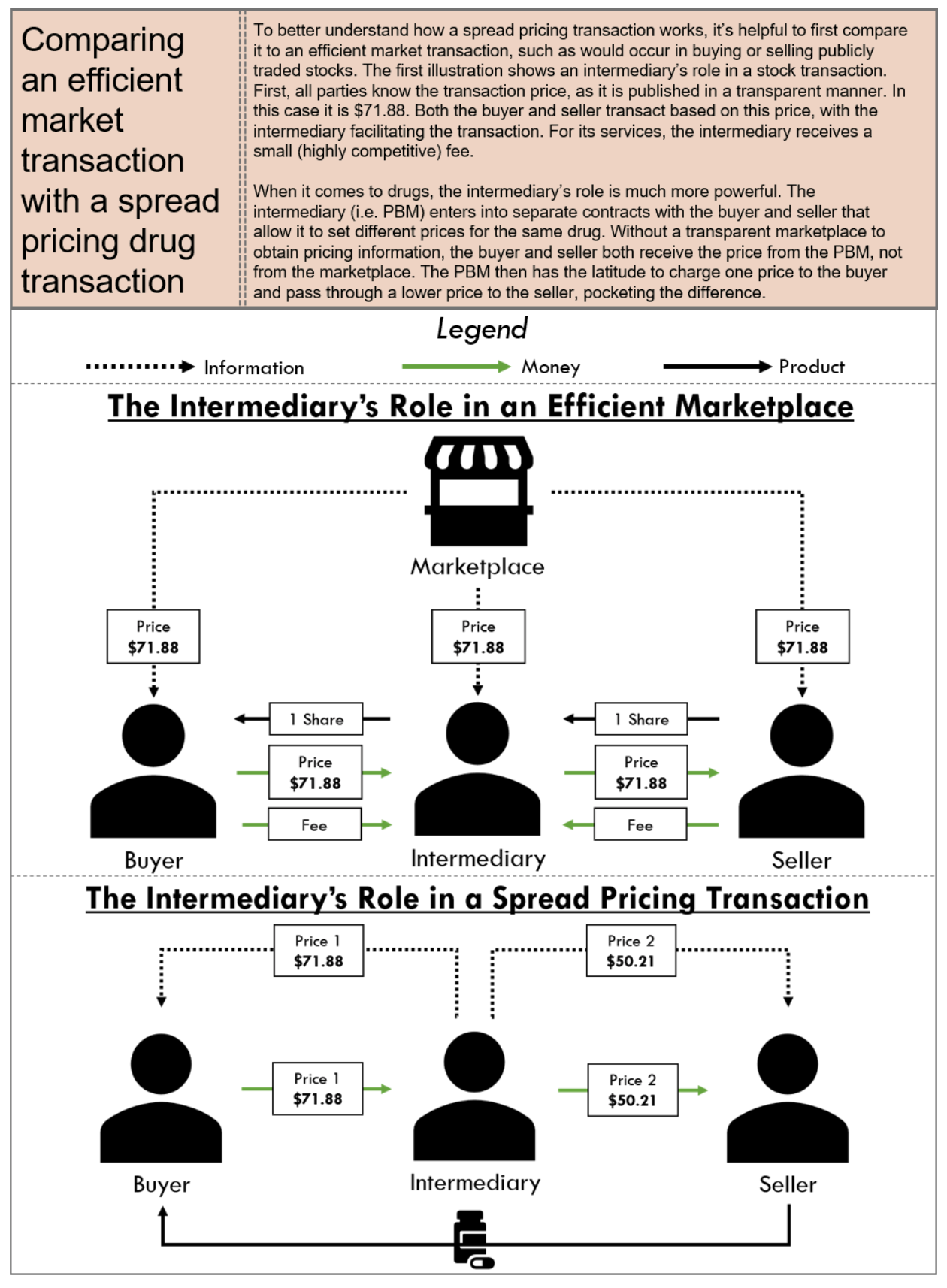

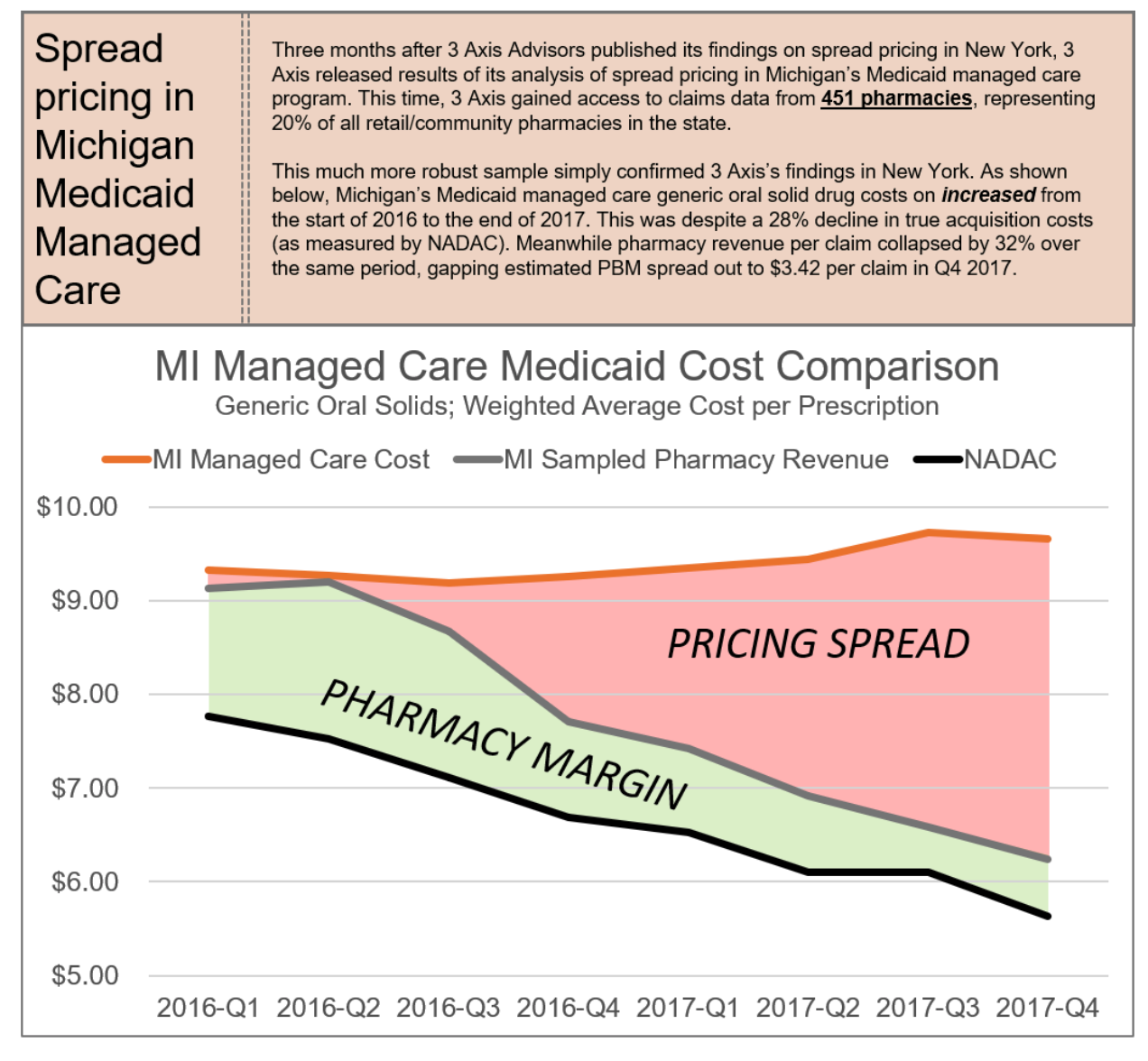

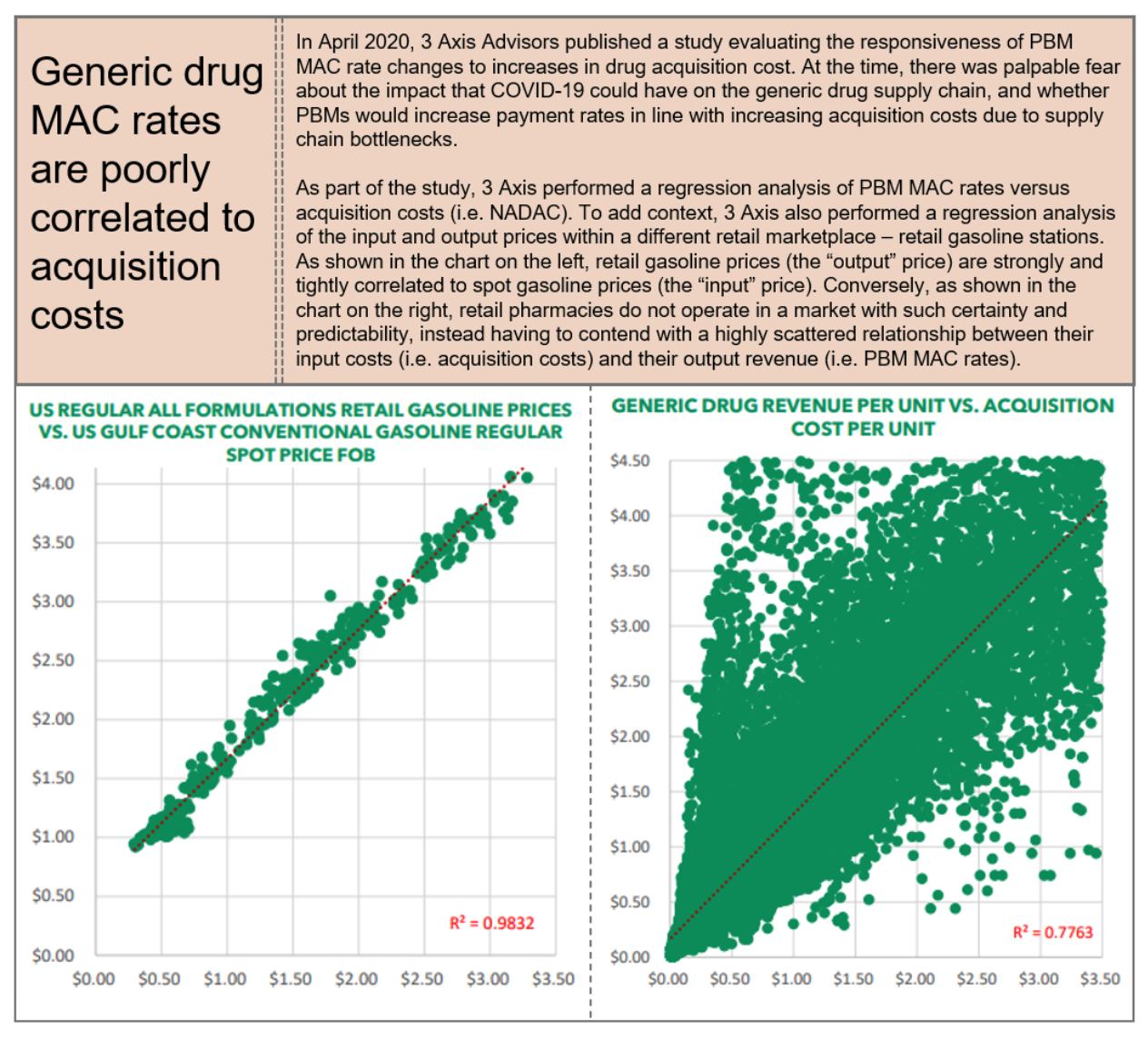

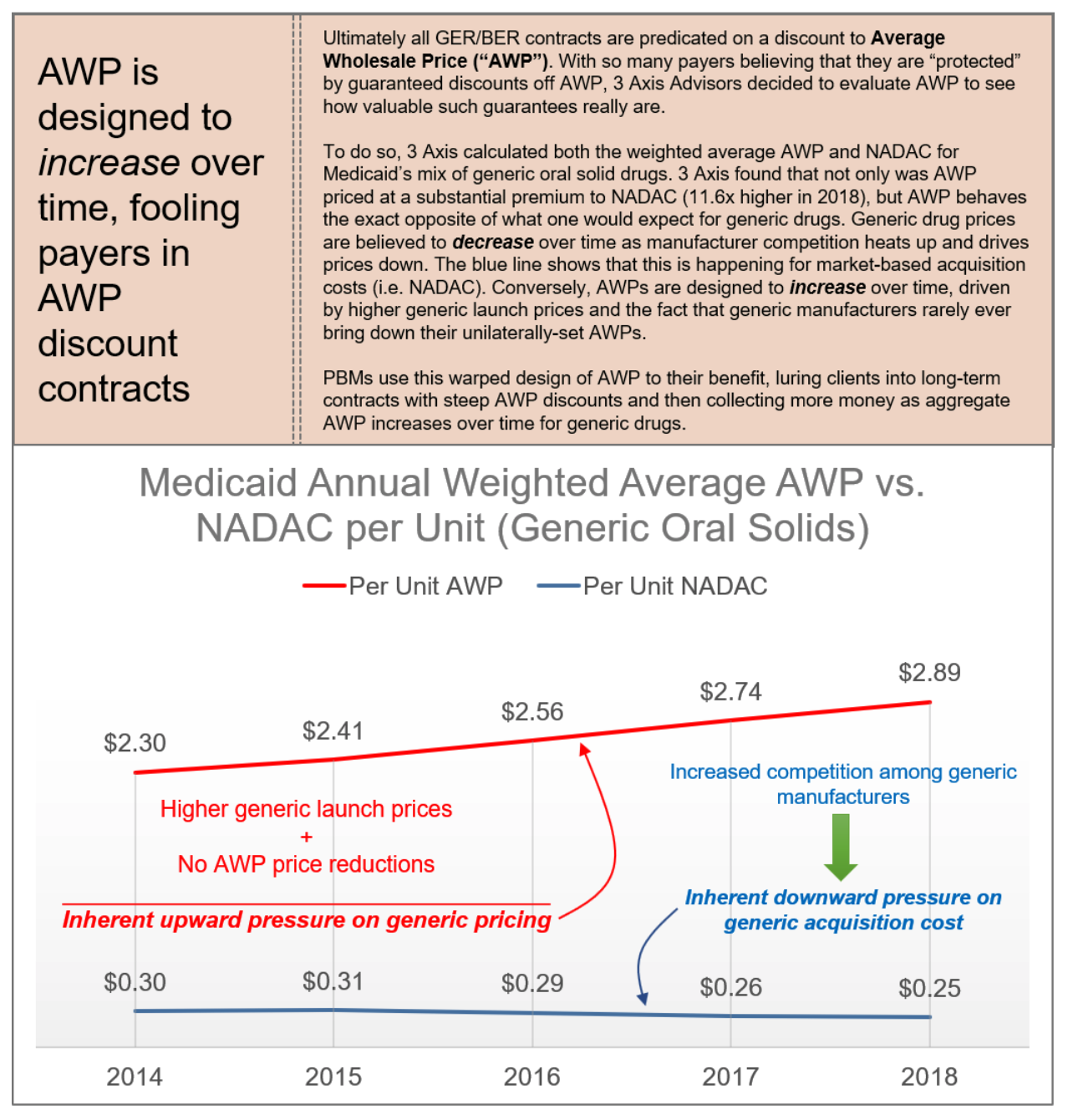

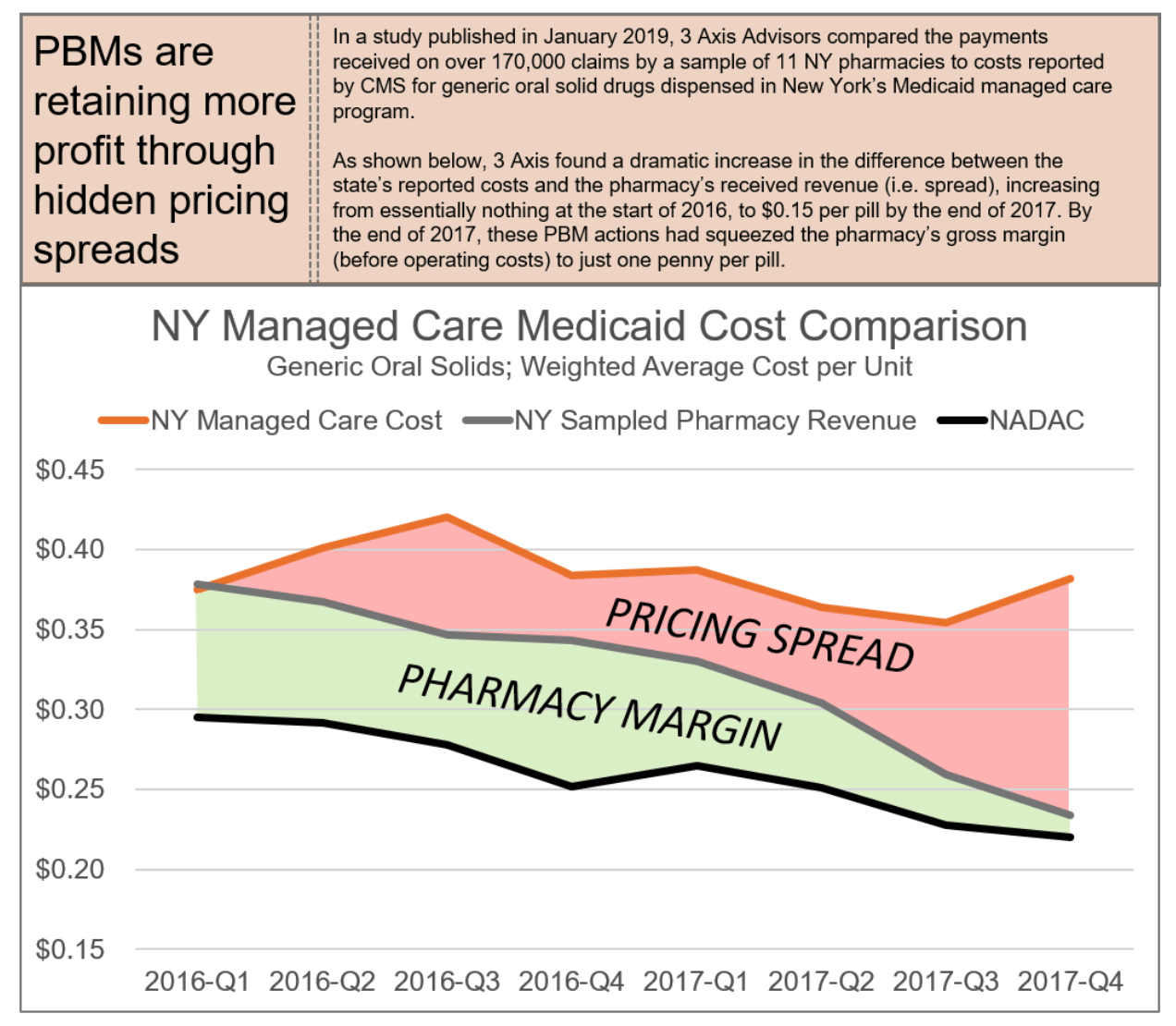

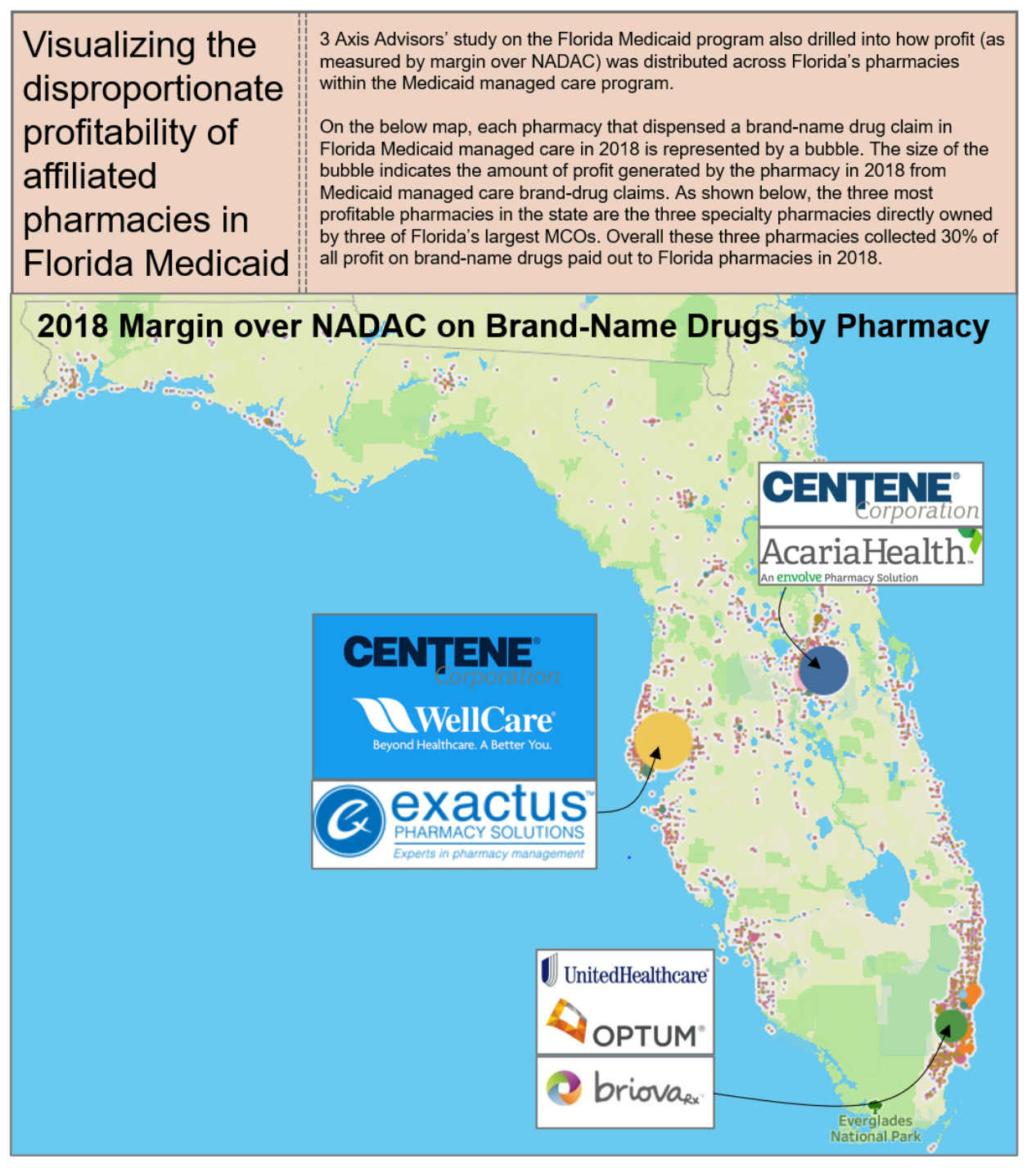

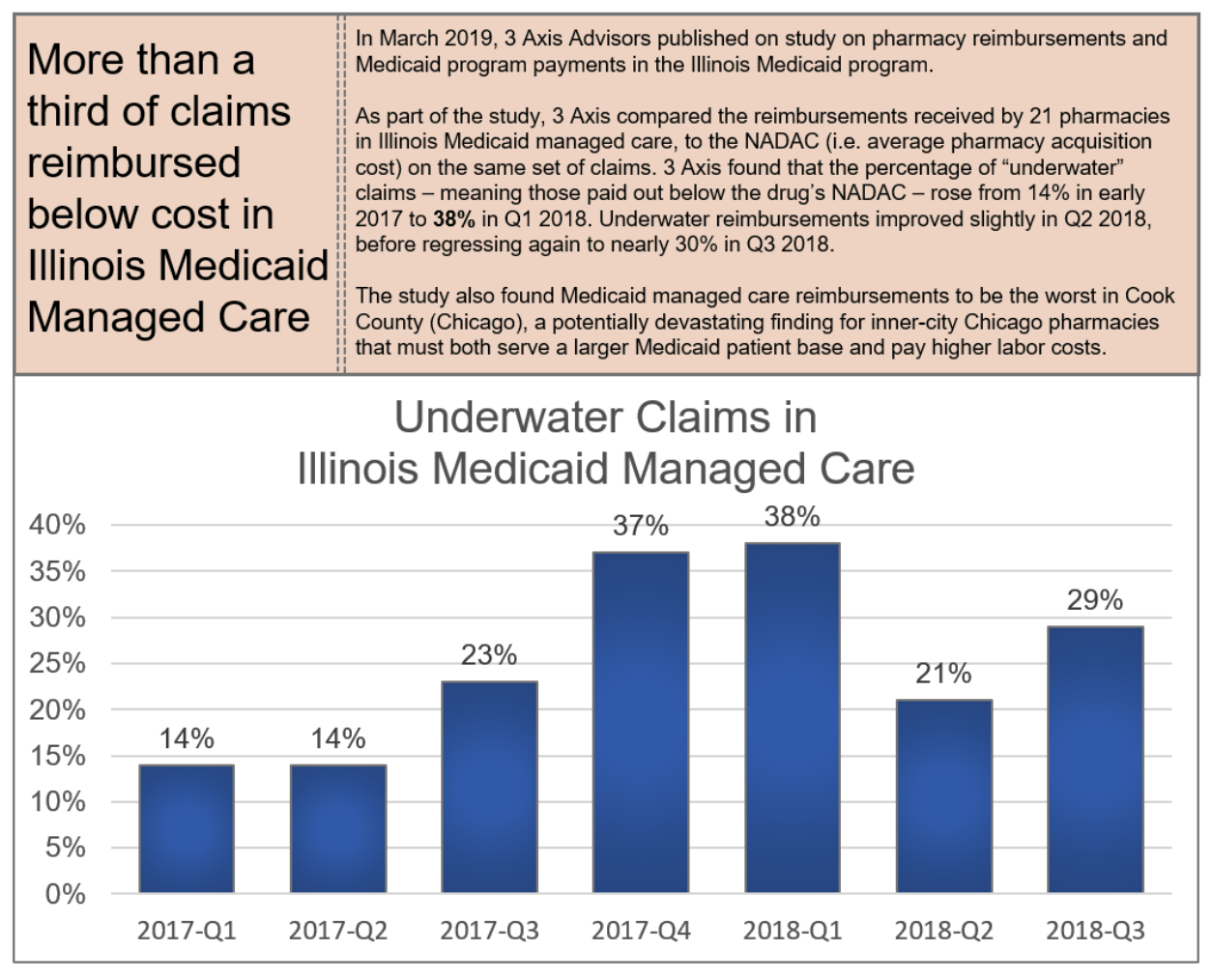

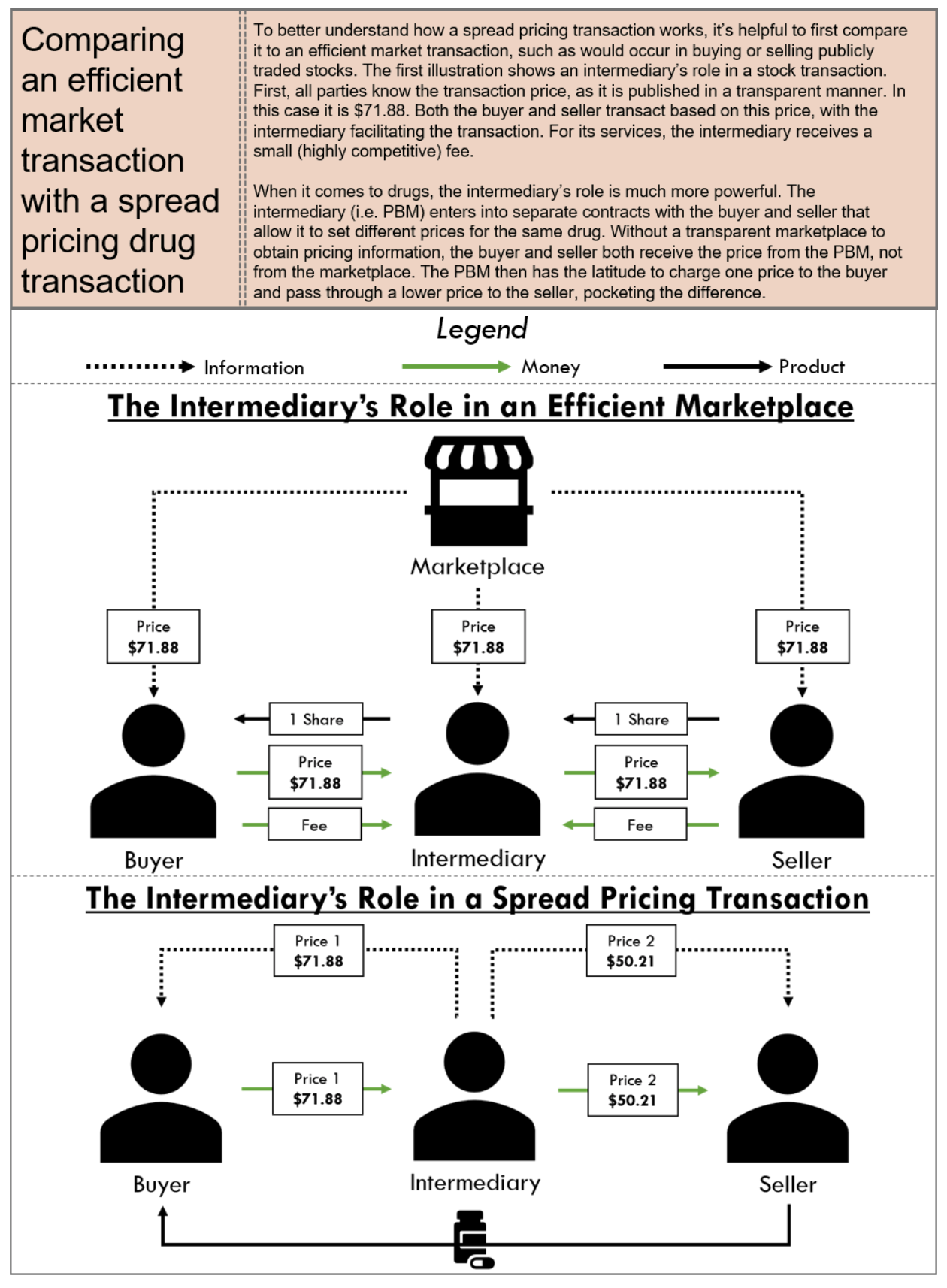

With the ultimate goal of this exposé being transparency, Frier Levitt went beyond the law, partnering with 3 Axis Advisors LLC to create infographics derived from their analysis of millions of prescription claims across multiples states. The goal of these infographics is to help crystallize and simplify the very complex topics we will discuss throughout this exposé. Lastly, because PBMs have been known to hold themselves out as being “above the law,” we have provided the applicable law and legal principles governing each topic, and detailed the PBMs’ thin legal footing as it comes to these abusive practices. Finally, we have laid out potential, workable solutions to these issues, which may be legislative, regulatory, or legal in nature.

We intend for this report to serve as an authoritative source and reference guide for federal and state policymakers, regulators, and employers seeking greater understanding of PBM behavior, as well as frameworks for reshaping the industry for the better. While not all PBMs engage in these types of practices, or the degree with which they engage in these practices may vary from plan to plan, program to program, state to state, and so on, we believe that a thorough exposure of the blind spots, latitude for abuse, and backwards incentives is essential for any coherent understanding of the inherent flaws within the drug supply chain.

This exposé was commissioned by the Community Oncology Alliance (COA). The findings reflect the independent research of the authors, Frier Levitt, LLC, and does not endorse any product or organization. If this exposé is reproduced, we ask that it be reproduced in its entirety, as pieces taken out of context can be misleading.

Background

3.1 The Stakeholders

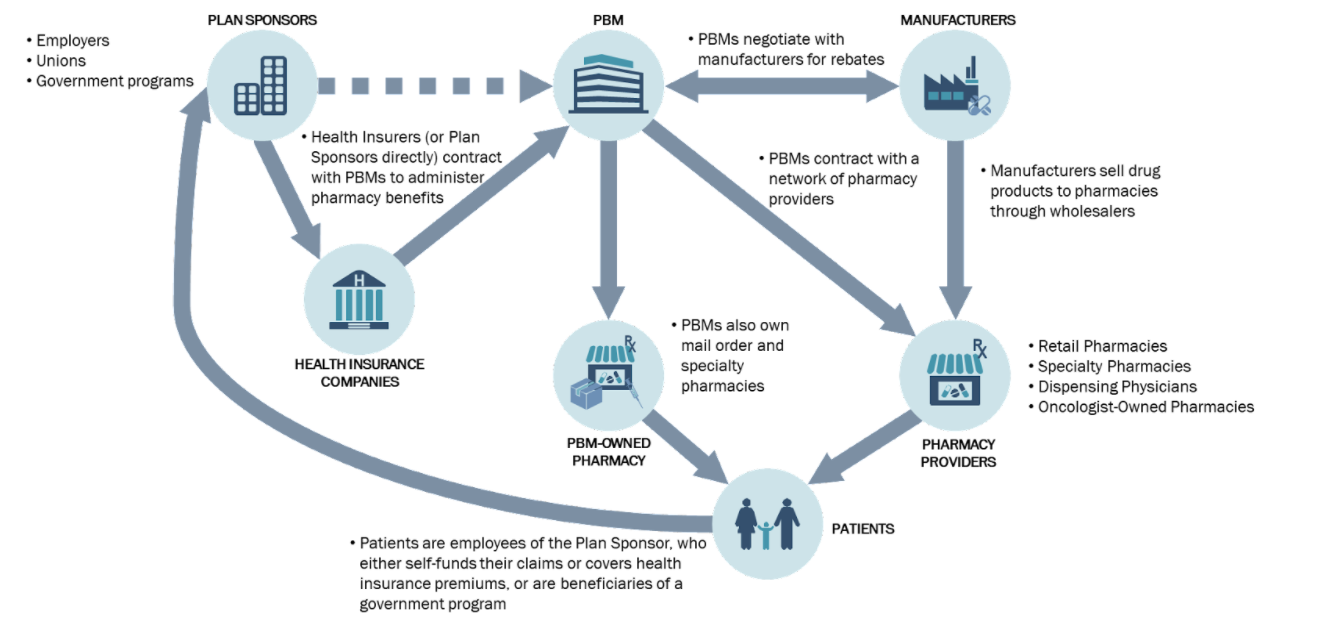

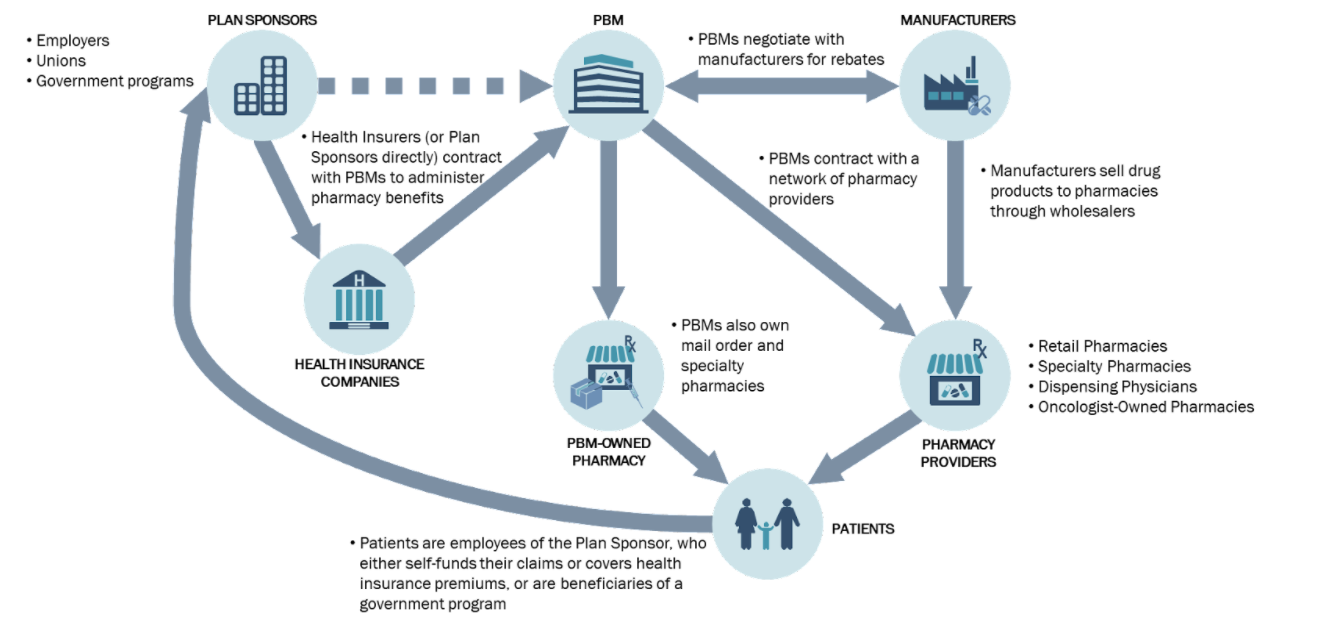

Any examination of the PBM industry must necessarily begin with an overview of the relevant stakeholders. These include five major categories of industry participants: (1) plan sponsors, (2) health insurers, (3) patients, (4) manufacturers, (5) providers, and (6) PBMs. Understanding who the major stakeholders are, and their relationship with one another, is paramount.

At the top of the hierarchy are plan sponsors. These include governmental health benefits programs (such as Medicare, Medicaid and TRICARE), employer-sponsored health plans, Taft-Hartley and union welfare plans, and private health insurance companies. These entities sponsor a health benefits plan for their members, beneficiaries or employees, and provide coverage for pharmacy expenses and drug costs (in addition to traditional medical expenses). In the Medicare Part D context, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) contracts with private insurance companies that submit bids to become Part D plan sponsors, and CMS in turn subsidizes certain costs associated with the operation of the plans. Likewise, in the Medicaid space, the majority of states operate a managed care model with respect to pharmacy benefits, contracting with Medicaid Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), who in turn, contract with PBMs to administer the pharmacy benefit. Finally, in the private sector, employers either directly or through an insurance company contract with PBMs to administer pharmacy benefits. These employer-sponsored plans may either be fully-insured (meaning the employer hires an insurance company and pays all or part of the premiums on behalf of its employees) or self-insured (meaning the employer bears all of the financial risk with the costs of care). In any case, these plan sponsors bear the ultimate costs of care, and suffer when PBM abuses cause prices to rise or waste to occur. Plan sponsors may or may not hire a health insurance company to help offset the risks associated with the cost of care, and pay premiums on behalf of their beneficiaries. These health insurance companies may in turn be the entity that directly contracts with the PBM for pharmacy care. However, as noted below, the lines have become increasingly blurred between health insurers and PBMs; thus, the key distinction between plan sponsors and health insurers is that the plan sponsors are typically the ultimate financial guarantors of the costs of the health care for their beneficiaries, including not only drug costs but also major medical expenses.

At the other end of the continuum are the patients. Patients include beneficiaries of government sponsored health care programs, as well as the employees (and dependents) of employers sponsoring health plans. They are also uninsured or underinsured individuals who are left to find a way to cover drug costs themselves. In oncology, they are cancer patients needing care from a complex and disjointed health care system. As a group, they not only bear a disproportionate share of the out-of-pocket costs associated with PBM abuses, but also suffer from the inferior care caused by certain PBMs’ tactics of putting profits over patients. These include delays and denials as a result of PBMs’ unnecessary obstacles to care.

On the front line of care are the providers. These include retail, specialty and mail-order pharmacies, and in oncology, community oncology practices. In addition to providing direct medical care, community oncology practices provide in-office and outpatient pharmacy services, which can take two basic forms (depending on applicable state law): dispensing physician practices (i.e., in-office dispensing under a plenary medical license), or oncologist-owned pharmacies (i.e., the oncology practice owns and operates a licensed retail pharmacy within the clinic). These providers contract with PBMs to dispense medication to plan members, and participate in PBM networks. In so doing, they are tasked with providing appropriate care to their patients, while remaining bound to the PBMs who set reimbursement rates and other terms for participation.

While not directly involved in the provision of care, manufacturers are equally part of the continuum and impacted by PBM actions. These include drug and biologic manufacturers, including both brand and generic companies. Manufacturers have had a particular important role in the biosimilar market, becoming captive to PBMs’ rebate traps, and stifling the biosimilar market before it even has a chance to take hold.

The final piece of the puzzle is the PBM. PBMs are third-party administrators of prescription drug programs covered by a plan sponsor. The PBM is primarily responsible for processing and paying prescription drug claims submitted by participating providers on behalf of covered beneficiaries. However, a PBM’s role is not limited to processing and paying prescription drug claims. Rather, PBMs also provide bundled services related to the administration of pharmaceutical benefits, including formulary design, formulary management, negotiation of branded drug rebates, and controlling network access of participating pharmacies. Perhaps most importantly, PBMs often also own and operate their affiliated retail, mail-order and/or specialty pharmacies, and in so doing, directly compete with independent providers participating in PBM networks. They are not just the gatekeepers, but also competitors operating in the same marketplace. This blatant conflict of interest has serious consequences. Finally, as the result of consolidation and vertical integration within the marketplace, virtually all of the major PBMs have merged with, acquired or become acquired by health insurers, greatly blurring the lines between insurer and PBM. As a result, health insurers and PBMs are often referred to jointly as “payers.”

Figure 1. The Pharmacy Benefits Landscape

The Figure 1, above, visually demonstrates the different stakeholders, and their relationship with one another.

3.2 Consolidation of PBMs and Health Insurers, and the Resulting Influence on Recent PBM Actions

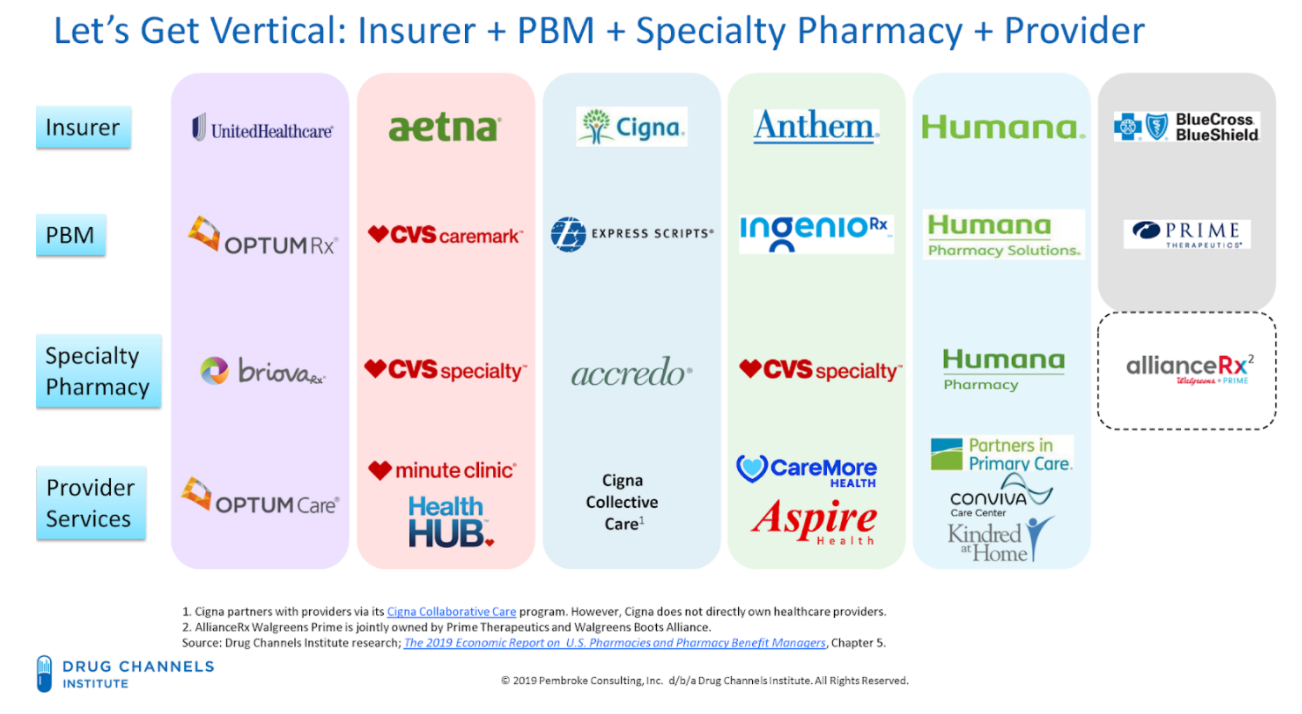

PBMs traditionally have played a critical role in the administration of prescription drug programs. However, over the past ten years, the PBM marketplace has transformed considerably. Changes include both horizontal and vertical integration among health insurance companies, PBMs, chain pharmacies, specialty pharmacies, and long-term care pharmacies. As a result, a smaller number of large companies now wield nearly limitless power and influence over the prescription drug market.

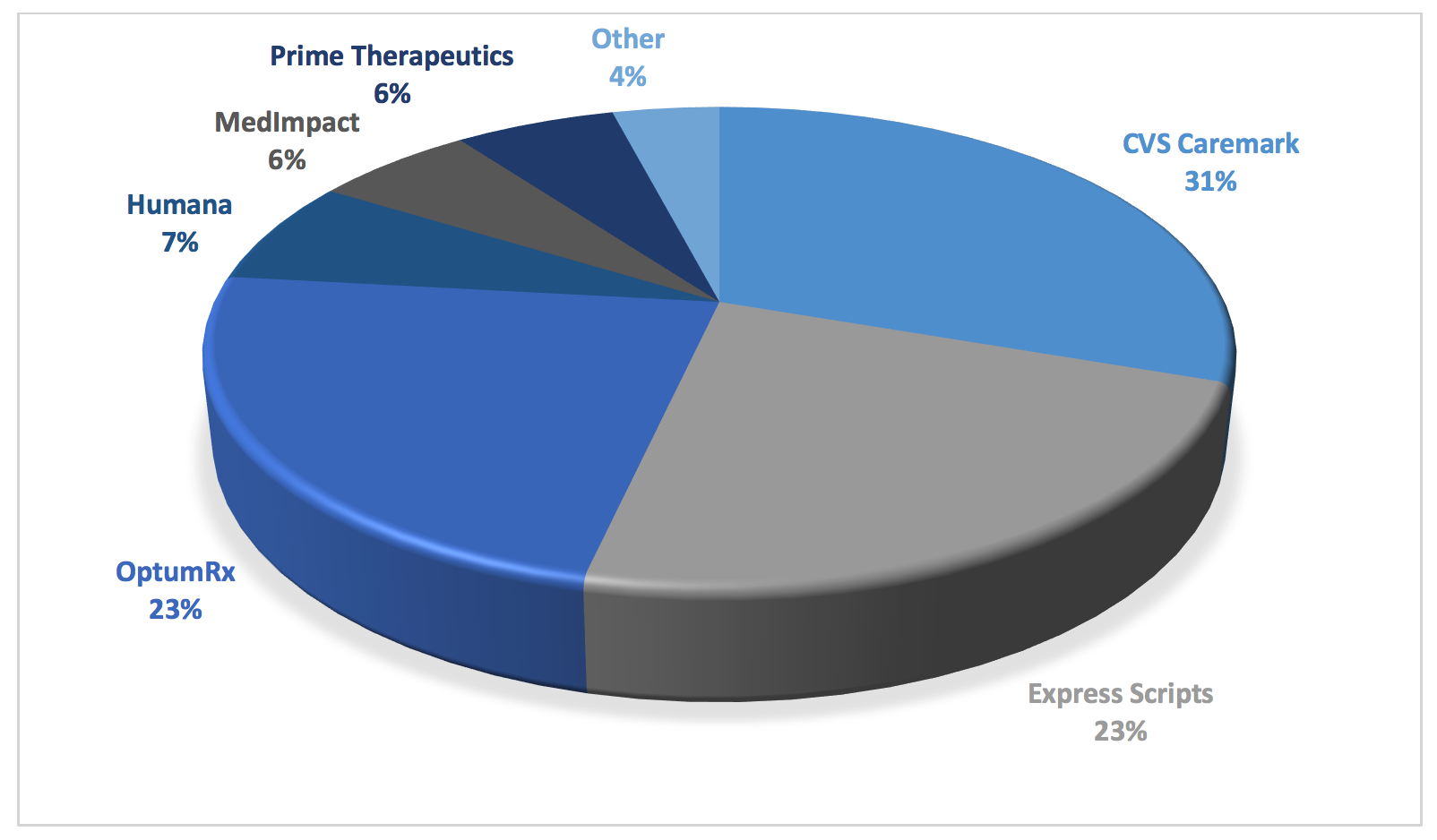

Within the PBM marketplace, over 80% of the covered lives in the United States are controlled by only five PBMs. As a result of this concentration, a pharmacy’s access to these five PBM networks is critical. Being out of network with just one PBM (which in some regions, could make up more than 85% of the market), and being unable to obtain reimbursement for claims dispensed to those patients, could make it financially unviable for any community oncology practice to provide dispensing services at all. The lack of competition in the marketplace stems, in large part, from a series of mergers, integrations, and consolidations. These consolidations and integrations are undoubtedly a factor in many abusive PBM practices, ranging from seeking to exclude independent providers, to reimbursement rates that force providers to lose money by filling prescriptions, to outright diversion of patients to the PBMs’ wholly-owned or affiliated pharmacies. The consolidation increases the market power of the top PBMs, which makes this possible.

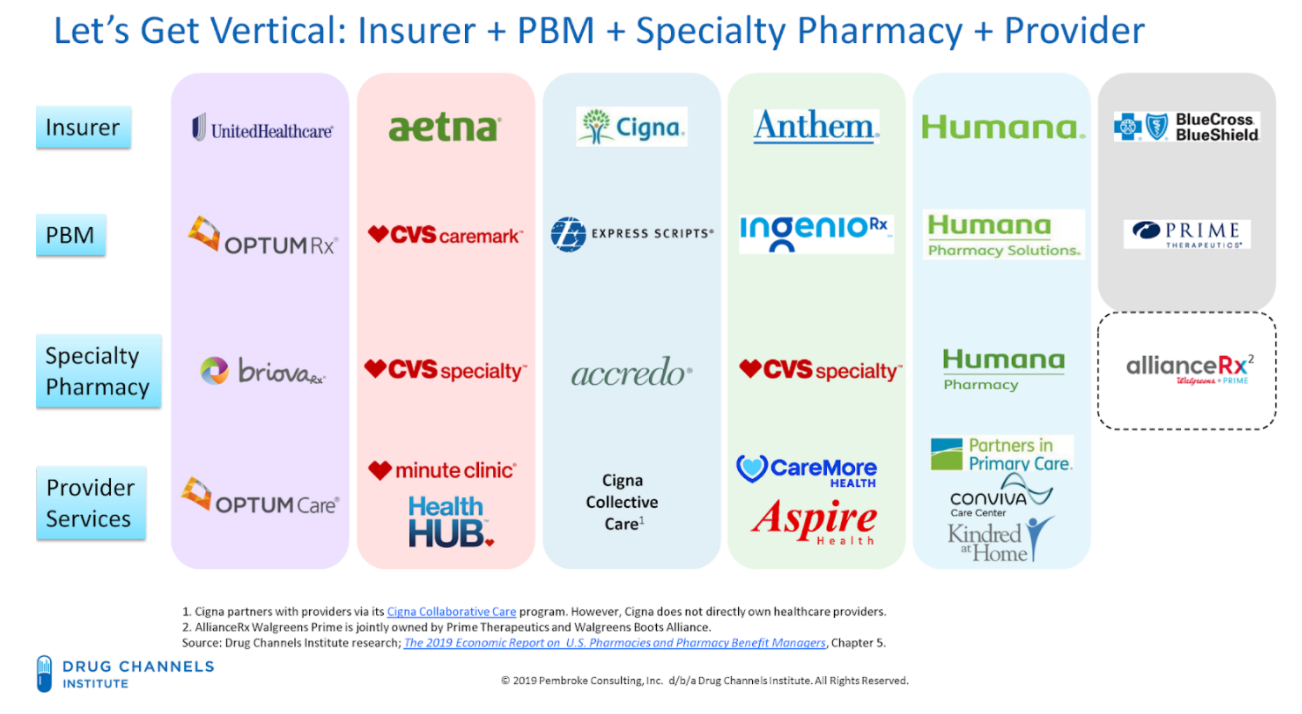

The breadth of PBM power did not arise overnight. It began with a series of vertical consolidations in which some PBMs acquired pharmacies and other PBMs acquired insurance companies. In 2007, the shareholders of Caremark Rx, one of the nation’s largest PBMs at the time, approved a $26.5 billion takeover of CVS Pharmacy, which effectively created the first vertically integrated retail pharmacy and PBM. Vertical integration of the industry continued in 2011, as Blue Cross Blue Shield of North Carolina, one of Medco’s largest customers, began shifting its PBM business away from Medco to Prime Therapeutics, a PBM that is wholly owned by a group of thirteen Blue Cross plans across the country. In 2012, UnitedHealthcare (United), the nation’s largest insurance company, began migrating the administration of its plans from Medco Health Solutions to OptumRx, United’s wholly-owned PBM.

Consolidation of the PBM and payer space has not been limited to vertical integration. In 2011, two of the nation’s then-largest PBMs – Medco Health Solutions, Inc. and Express Scripts, Inc. – announced a $29 billion merger. After a contentious regulatory approval process, the Federal Trade Commission ultimately approved the merger in 2012.

Thereafter, the industry continued consolidation both horizontally and vertically. In 2013, a regional PBM – SXC Corporation – agreed to buy another regional PBM – Catalyst, Inc. – for $4.4 billion to form a national PBM, known as Catamaran Corp. In July 2015, Catamaran was acquired by United, OptumRx’s parent company, for $12.8 billion. The two PBMs are now integrating operations and operate under one name, OptumRx. In 2015, Rite Aid acquired the PBM EnvisionRx for approximately $2 billion. Later that year, Walgreens announced its intention to acquire Rite Aid and EnvisionRx for $9.4 billion. Also in 2015, Aetna, the nation’s third-largest insurer, announced its intention to acquire Humana, the nation’s fourth-largest insurer, as well as Humana’s wholly-owned PBM, Humana Pharmacy Solutions, for $37 billion. Finally, in 2015, Anthem announced its agreement to buy Cigna (including its PBM arm) for $48 billion, which would result in, yet again, fewer players in the space. However, on July 21, 2016, the Justice Department filed lawsuits to block both the Aetna-Humana and Anthem-Cigna mergers, asserting that the mergers would quash competition, leading to higher prices and reduced benefits.

Figure 2. PBM Mergers and Consolidations in Last Ten Years

Unfortunately, the last five years has only seen this trend of consolidation and integration expand at an exponential rate. In November 2018, CVS Health completed a controversial $69 billion acquisition of Aetna, a managed health care company that specializes in selling traditional and consumer-directed health insurance along with related services including dental, vision, and disability plans. Not to be outdone, in December 2018, health insurer Cigna acquired Express Scripts for $54 billion. Since that time, Cigna and Express Scripts have continued to expand in creative ways. In December 2019. Express Scripts and Prime Therapeutics announced a three-year collaboration agreement, whereby Express Scripts would take over the contracting and administration of the pharmacy benefits for Prime Therapeutics’ members. As a result of the arrangement, Express Scripts will now manage the prescription benefits for more than 100 million Americans.

Figure 3. Vertical Integration of PBMs and Health care Conglomerates

This rapid evolution of the PBM and health insurance industry shows how a limited number of corporations wield an outsized level of control and influence in the prescription drug coverage marketplace. Fewer payers spells harm to patients, especially cancer patients. These integrated companies have greater abilities to control the nature and direction of patients’ care, including what type of care/drugs they receive, from whom they receive it, and in what setting they are treated. The level of PBM intrusion into the care received by patients borders on the practice of medicine by these PBMs and health insurance conglomerates.

Fewer payers also results in harm to plan sponsors, especially employers sponsoring health plans, who have fewer choices based on decreased competition. This hits small employers the hardest, who lack the overall leverage and resources to either demand competitive rebates or restructure entrenched PBM practices.

Fewer payers also exponentially increases the importance of network access for providers. Exclusion from one PBM with a market share of 35% means that the provider loses out on a major portion of the patient population.

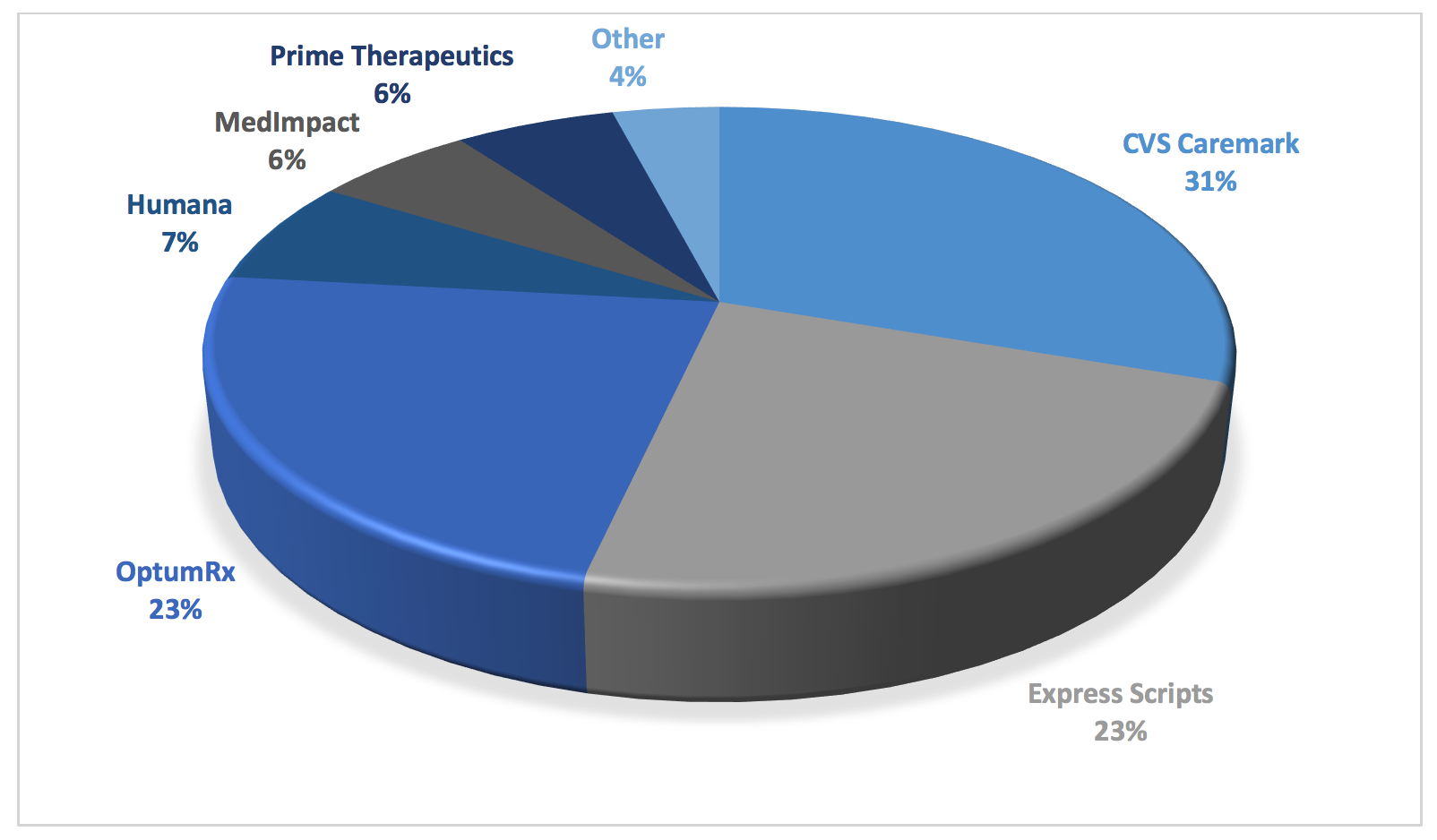

Figure 4. Market Share by PBM in U.S. Prescription Benefits Market in 2018

As can be seen in the figure above, consolidation has created merged entities that have oppressive power. This creates a virtual chokehold note only on community oncology practices and pharmacy providers, but on plan sponsors and patients alike. It is through this market dominance that PBMs are able to get away with their abuses. Whether it is outsized rebates and DIR fees fueling drug prices. Whether it is unreasonable barriers to entry, network exclusions, or mandatory white bagging forcing patients to receive inferior service at higher costs. Whether it is employing insidious copay accumulator programs or deceptive pricing and reimbursement techniques. Or worse yet, whether it is essentially practicing medicine, through “fail first” step therapy, prior authorization requirements, or formulary exclusions, many of which favor not the least expensive medication, but the most profitable one for the PBM. Each of these tactics are made possible by the PBMs’ sheer levels of dominance at all levels of the health care continuum. This consolidation has hurt medical care while fueling both drug prices and costs to patients and plan sponsors alike.

While the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ) Antitrust Division recently embarked on a process to rewrite vertical merger guidelines, this effort is seen by many as coming “too little, too late.” Providers, patients, and plan sponsors have long realized that the vertical integration between payer-PBM-provider would spell disaster for quality and freedom of choice. Dramatic and urgent action is necessary to curtail this wide-ranging abuse of power.

Manufacturer Rebates, Rebate Aggregators, and the “Gross-to-Net Bubble”

It is axiomatic to say that the PBM market is highly concentrated, with three companies (i.e., CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, and OptumRx) covering nearly 80 percent of the market or 180 million American lives. As a result, pharmaceutical and biosimilar manufacturers face exceedingly high stakes when negotiating for formulary placement. Among the different sources of revenue, the most prolific by far is in the form of rebates from pharmaceutical manufacturers that PBMs extract in exchange for placing the manufacturer’s product drug on a plan sponsor’s formulary or encouraging utilization of the manufacturer’s drugs. Rebates are mostly used for high-cost brand-name prescription drugs where there are interchangeable products and aim to incentivize PBMs to include pharmaceutical manufacturers’ drugs on plan sponsors’ formularies and to obtain preferred tier placement.

While drug prices are too high, ironically, the growing number and scale of rebates is the primary fuel of today’s high drug prices. The truth is that PBMs have a vested interest to have drug prices remain high and to extract rebates off of these higher prices. PBM formularies tend to favor drugs that offer higher rebates over similar drugs with lower net costs and lower rebates.

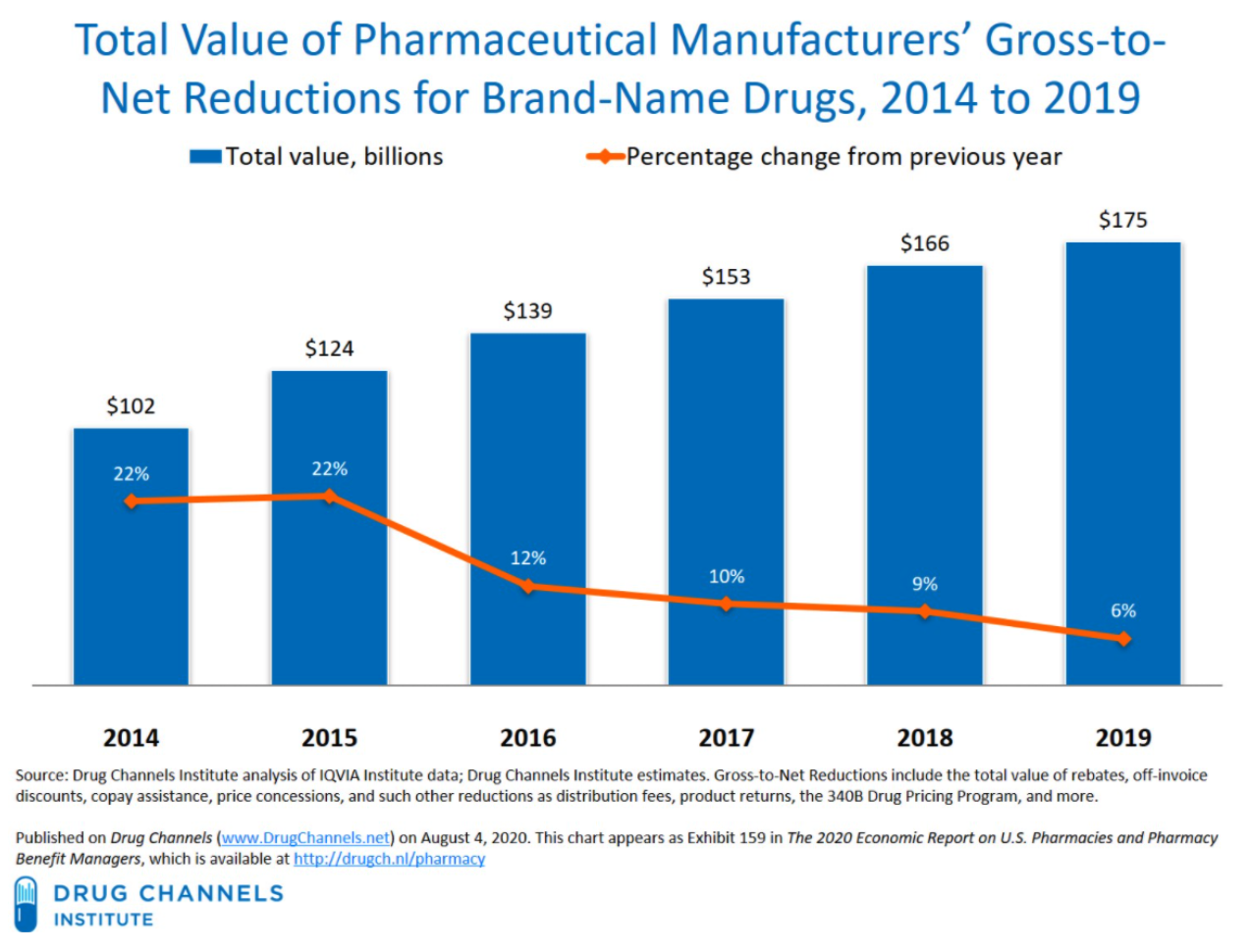

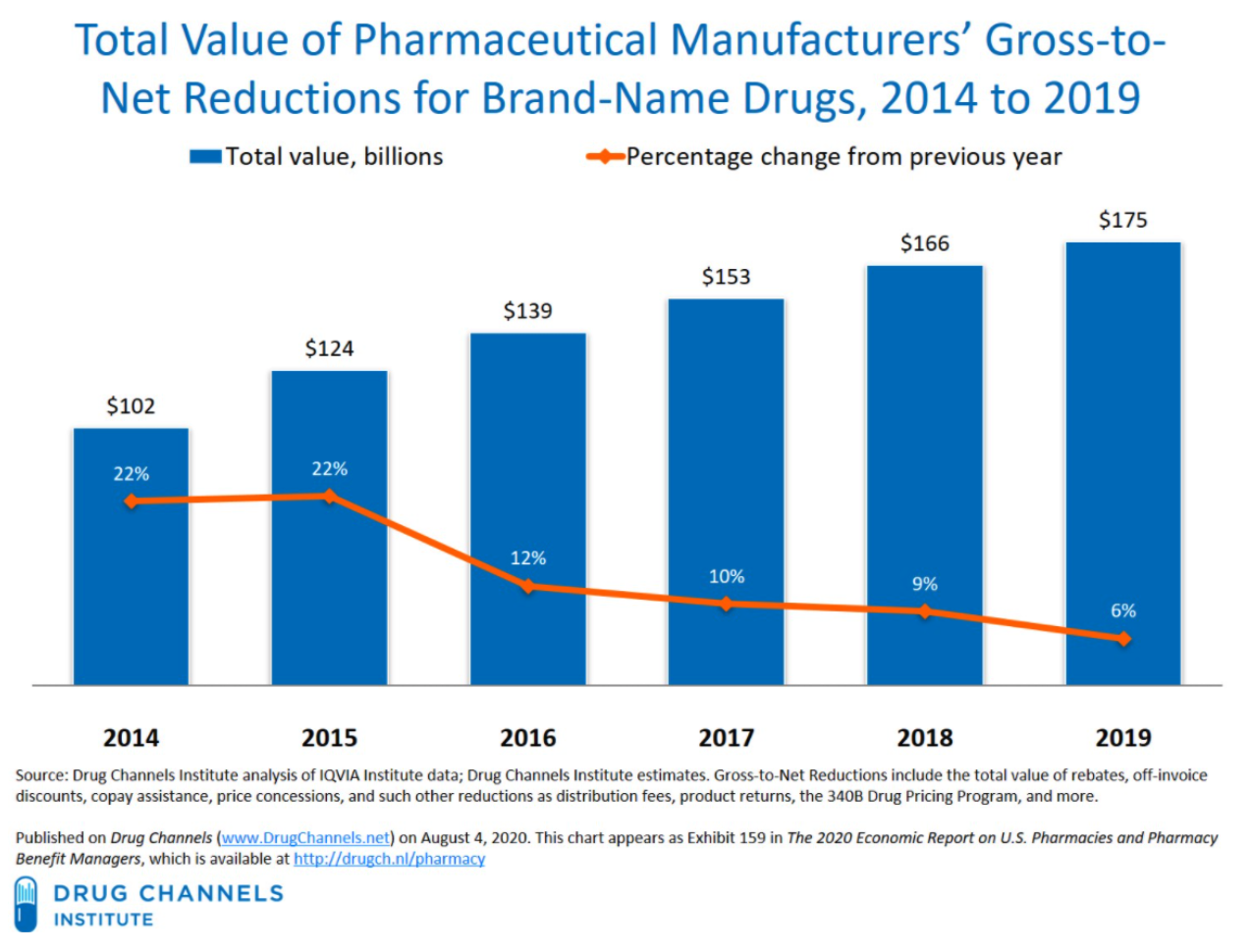

Figure 5. Gross-to-Net Bubble

Apart from increasing costs today, these destructive practices will have a long-lasting impact on the future of health care and drug innovation. Traditionally, generic drugs offer significant price relief for brand medications; however, there are an ever-growing subset of medications that are unlikely to ever have a traditional generic alternative. As a result, federal policy was enacted to create eventual competition for these brand products such as the biosimilar pathway. However, the PBMs’ practice of maximizing rebates may effectively neuter the nation’s biosimilar market before it even gets off the ground. Unlike traditional drug products, biologics are unique and complex molecules and represent many of the new breakthrough treatments that have come to market over the past ten years. But with such breakthrough comes extremely high cost. As a result, biosimilars – that is, products that are “highly similar” to the reference biologic – have emerged to provide alternatives and competition in the biologics space. The first biosimilar product in the United States was approved in March 2015 and marketed in September 2015. The greater use of biosimilars has the potential to reduce the overall drug spending, while providing greater clinical options for providers and patients. However, PBMs and biologics manufacturers have erected “rebate walls” that have severely depressed biosimilar development and widespread adoption. According to former FDA Commissioner, Dr. Scott Gottlieb, Americans could have saved more than $4.5 billion in one year alone, if they had bought FDA-approved biosimilars. While the FDA had approved 11 biosimilars through 2018, only three were then being marketed in the U.S. As of January 2022, nearly 32 biosimilars have been approved, while only 29 are currently being marketed. PBM rebates represent a clear and existential threat to the future of the biosimilar marketplace.

As the American public and plan sponsors have become more aware of the nature and extent of rebates, they have begun demanding that all or nearly all rebates negotiated on their behalf be fully reported and passed-through. As a result, PBMs have begun to market themselves as transparent and assert that many of their customers are able to negotiate “pass-through pricing” allowing pharmaceutical manufacturer rebates and other concessions to flow directly to plan sponsors. However, a dangerous new trend has grown exponentially over the last few years through which PBMs seek to “circumvent” these pass-through requirements. PBMs have increasingly “delegated” the collection of manufacturer rebates to “rebate aggregators,” which are often owned by or affiliated with the PBMs, without seeking authorization from plan sponsors and without telling plan sponsors. Sometimes referred to as rebate GPOs, these mysterious entities include Ascent Health Services, a Switzerland-based GPO that Express Scripts launched in 2019, Zinc, a contracting entity launched by CVS Health in the summer of 2020, and Emisar Pharma Services, an Ireland-based entity recently rolled out by OptumRx. Even some of the major PBMs (i.e., the “Big Three” PBMs) sometimes find themselves contracting with other PBMs’ rebate aggregators for the collection of manufacturer rebates (for example, in the case of OptumRx contracting with Express Scripts for purposes of rebate aggregation for public employee plans).

In both the private sector and with respect to government health care programs, the contracts regarding manufacturer rebates (i.e., contracts between PBMs and rebate aggregators, as well as contracts between PBMs/rebate aggregators and pharmaceutical manufacturers) are not readily available to plan sponsors. Moreover, PBMs do not provide plan sponsors access to claim-level rebate information unless demanded through the contracts entered by and between plan sponsors and PBMs.

Within Medicare Part D, Part D Sponsors are required to submit Direct and Indirect Remuneration (DIR) reports to CMS disclosing the total amount of rebates, inclusive of manufacturer rebates, retained by PBMs regardless of whether such rebates were passed to Medicare Part D plan sponsors. And while PBMs and rebate aggregators are obligated to provide, among other things, the aggregate amount and type of rebates, discounts, or price concessions to the plan sponsors (who in turn provide the same to CMS), PBMs and rebate aggregators do not have to provide claims-level information on the actual amounts received on behalf of plan sponsors.

4.1 Who is Impacted?

The deleterious effects of rebates, and the furtive work of rebate aggregators, are felt across the health care spectrum.

4.1.1 Harm to Patients

Whether a patient has insurance or not, rebates serve to increase the overall costs of drugs and out-of-pocket expenditures for patients. With one in four people in the United States having difficulty paying the cost of their prescription medications, the extent of the negative impact of rebates is felt far and wide.

For uninsured patients, the rebates negotiated by a PBM or health insurance company do nothing to lower their out-of-pocket costs. Rebates promote high drug list prices. “Higher drug prices hurt uninsured patients who pay list prices … based on drugs’ list prices.” And because these rebates are received and kept among secretive health care conglomerates, and not shared with providers or other groups, even discount programs like GoodRx do little to help uninsured patients receive savings on the most expensive drugs.

Even for patients with insurance, rebates ultimately increase costs to the patient for the benefit of PBMs and health insurers. At the point of sale, the inflated list prices caused by rebates “hurt … insured patients who pay coinsurance and deductibles based on drugs’ list prices.” Over the past several years, the number of patients on high-deductible health plans has skyrocketed. This has turned the insurance market upside down, causing the relatively small number of sick patients who pay high copays off of inflated list prices to subsize the cost of care for healthy people. In this form of “reverse insurance,” the sickest patients (e.g., those taking expensive cancer medications) generate a large share of manufacturer rebate payments, which in turn are used to “subsidize the premiums for healthier [patients].” This is the opposite of how insurance is supposed to work.

What’s worse, PBMs’ preference of highly-rebated drugs not only increases patients’ out-of-pocket expenses, but also creates unnecessary burdens in receiving appropriate care, even to the point of fatality. PBMs have an incentive to favor high-priced drugs over drugs that are more cost-effective, because rebates are often calculated as a percentage of the manufacturer’s list price. PBMs receive a larger rebate for expensive drugs than they do for ones that may provide better value at lower cost. This can also occur “when a brand drug goes generic under the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, with the first generic version being granted six months of market exclusivity,” and “[i]n exchange for substantial rebates, manufacturers [are given] an exclusive extension of their brand drug, which circumvents Hatch-Waxman and blocks generic competition.” PBMs’ financial motivations often result in more expensive and less efficacious drugs being placed on the drug formulary, which in turn hurts patient care.

Again, PBMs are able to do this because of the sheer levels of market consolidation and integration, which is adversely impacting cancer care and fueling drug costs all in the interests of PBM profits.

4.1.2 Harm to Plan Sponsors

While rebates are intended to lower the “net price” of drugs, thereby reducing costs to plan sponsors (including employers), there are several important ways that PBM rebates increase the costs of drugs for both plan sponsors and patients.

The first way relates to the ability of plan sponsors, especially self-funded employers, to ensure the full amount of rebates are reported and passed through to them by PBMs. As noted above, it is extremely difficult to gauge the true amount of drug manufacturer rebates collected by PBMs, and this is only made more difficult by the advent of rebate aggregators. Unlike in the Medicare Part D program, PBMs typically do not legally owe self-funded employers any reporting on rebates. PBMs employ exceedingly vague and ambiguous contractual terms to recast monies received from manufacturers outside the traditional definition of rebates, which in most cases must be shared with plan sponsors. Rebate administration fees, bona fide service fees, and specialty pharmacy discounts/fees are all forms of money received by PBMs and rebate aggregators which may not be shared with (or even disclosed to) the plan sponsor. These charges serve to increase the overall costs of drugs, while providing no benefit whatsoever to plan sponsors.

And while there might be greater reporting and disclosure obligations in the Medicare Part D and Medicaid programs, the growth of rebate aggregators has created a way for PBMs (or their corporate affiliates) to retain rebates and not share them with plan sponsors. This causes the Part D plan sponsor to become liable to CMS to “true up” any reductions in cost caused by these rebates, despite the fact that the Part D plan sponsor never actually received any rebates. Moreover, studies have shown that PBM rebates extracted from drug manufacturers drive up the drug spending of plan sponsors including Medicare and Medicaid. This is especially draining on already budget-strapped state governments. Since Medicare Part D is financed through general revenues, beneficiary premiums, and state payments for dual-eligible beneficiaries (who received drug coverage under Medicaid prior to 2006), rebates also drive up the drug spending of the participating states and in turn, taxpayers’ financial obligations to support Medicare Part D and Medicaid continues to rise. The total drug spend of a plan sponsor, regardless of whether it is a federal or state governmental program or a self-funded employer, will inevitably increase because PBMs are incentivized to favor expensive drugs that yield high rebates. In some instances, PBMs purposely misclassify generic drugs as brand drugs to charge higher prices to plan sponsors, which ultimately generate higher rebate revenue. Moreover, the gross-to-net bubble (i.e., the dollar difference between sales at brand-name drugs’ list prices and their sales at net prices after rebates, discounts, and other reductions) has been growing at an exponential pace. The upward trend in the gross-to-net bubble reached $175 billion in 2019. Based on this trend and the fact that plan sponsors are not receiving full value of the rebates from PBMs, it is evident that rebates increase total drug spend of plan sponsors and only benefit PBMs.

The final and perhaps most long-term impact that rebates will have on plan sponsors is in the suppression of the biosimilar market. The greater use of less expensive biosimilars (essentially “generic” versions of biologic medications) has the potential to reduce overall drug spending. However, many health plans do not include biosimilars in their preferred tiers. This is because of the “rebate trap,” where PBMs prefer the higher cost, branded biologics that offer rebates, over cheaper biosimilar alternatives. The result is that when biosimilars do make their way to the market, many patients do not have access to them because their PBM does not cover it. These policies stifle advancements, and will, in the long term, keep plan sponsors beholden to higher cost, branded medications.

4.1.3 Harm to Providers

Finally, rebates also impact providers in several ways. First, PBMs preference of highly rebated drugs limits providers’ choice of optimal drug therapy for patients. Once again, this results in the PBM inserting itself in between the prescribers and their patients and violates the sanctity of the doctor-patient relationship. This is especially true with biosimilars. The greater use of biosimilars has the potential to reduce overall drug spending and provide greater clinical options for providers, including community oncology practices. However, due to rebates, many PBMs do not include biosimilars in their preferred tier, thereby preventing widespread adoption and cost savings.

In instances where biosimilars are included on formularies, this is done so inconsistently and on a patchwork basis, tied solely to the rebates that the PBM can extract from the drug manufacturer, and not the efficacy of the product. The result is that community oncology practices often are required to stock several different versions of very expensive biosimilars based on the rules of the patient’s PBM, rather than being able to prescribe and dispense the product that is best suited for their patients.

Rebates further intrude on the doctor-patient relationship when combined with step therapy, prior authorization, or other utilization management protocols. “Fail first” step therapy requires a patient to first fail once or twice on a medication specified by the PBM or health insurer before being allowed to “step up” to the therapy prescribed by the physician. In many cases, the medication dictated by the PBM or health insurer is not the least expensive medication, but rather, is the most profitable drug to the PBM due to rebates. The impact of step therapy, driven by rebating, is that it “takes the medical decision-making out of the hands of doctors” and puts it into the hands of the actuaries, accountants, and business people at the PBM, who are not choosing the drug that is most efficacious, or cheapest, or even most efficient – they are choosing the drug that is the most profitable.

4.2 What Does the Law Say?

Medicare Part D plan sponsors are required to submit DIR reports to CMS disclosing the total amount of rebates, inclusive of manufacturer rebates and pharmacy rebates, retained by PBMs regardless of whether such rebates were passed to Medicare Part D plan sponsors.

In the commercial market, many states have enacted laws that require transparency from PBMs and “pass through” pricing. For example, Delaware House Bill 194 enacted into law on July 17, 2019, permits the Insurance Commissioner to examine the affairs of PBMs, among other things. Likewise, under New York Senate Bill S1507A enacted into State Budget for the 2019-2020 Fiscal Year on April 12, 2019, PBMs are required to fully disclose to the Department of Health and plan sponsors the sources and amounts of all income, payments, and financial benefits. Similarly, Utah House Bill 272, which was enacted into law on March 30, 2020, requires PBMs to report all rebates and administrative fees to the Insurance Department including the “percentage of aggregate rebates” that PBMs retained under its agreement to provide pharmacy benefits management services to plan sponsors.

However, Maine Bill 1504, enacted into law on June 24, 2019, takes these reporting requirements a step further, and provides that “[a]ll compensation remitted by or on behalf of a pharmaceutical manufacturer, developer or labeler, directly or indirectly, to a carrier, or to a pharmacy benefits manager under contract with a carrier, related to its prescription drug benefits must be: A. Remitted directly to the covered person at the point of sale to reduce the out-of-pocket cost to the covered person associated with a particular prescription drug; or B. Remitted to, and retained by, the carrier. Compensation remitted to the carrier must be applied by the carrier in its plan design and in future plan years to offset the premium for covered persons.”

4.3 What Can Be Done?

If high drug prices meaningfully addressed then outsized negative impact of rebates, rebate aggregators, and the resulting high gross-to-net bubble must be addressed. Luckily there are several varied options available to the affected parties:

- Legislative

- Policymakers should enact laws that mandate PBMs and rebate aggregators to report drug manufacturer rebates procured by utilizing drugs dispensed to plan sponsors’ patients in a given year. Requirements set forth under 42 CFR § 423.514(d) are not sufficient to cast the light of full transparency on PBMs (and rebate aggregators) that contract with Medicare Part D plan sponsors.

- Laws should be enacted that allow plan sponsors to gain access to the drug manufacturer rebates reported by PBMs and rebate aggregators.

- Laws should be enacted that entitle Medicare Part D plan sponsors and state Medicaid agencies to conduct full and complete audits of PBMs and rebate aggregators and these entities should not have any ability to limit the scope and extent of such audits.

- Laws should be enacted that limit Medicare Part D plan sponsors’ financial obligation to CMS in the event that PBMs and rebate aggregators retained drug manufacturer rebates that were not relayed to Medicare Part D plan sponsors.

It should be called out that some in Congress have the mistaken belief that drug manufacturers are the primary beneficiary of rebates in terms of “buying” formulary access for their drugs. Although this may be true in a limited number of cases, the reality is that PBMs use rebates to extract – some would say “extort” – drug manufacturers to pay the rebate “toll” in order for PBMs to include these drugs on formulary or to avoid being part of a “fail first” step therapy scheme. Congress has been held hostage to PBMs and their corporate affiliated health insurers by threatening to increase plan premiums if rebates are eliminated or made illegal.

- Plan Sponsor Action

- As part of the PBM contracts, plan sponsors should:

- Require PBMs to seek approval from plan sponsors prior to delegating the rebate aggregation function to rebate aggregators.

- Require PBMs to disclose a list of rebate aggregators to plan sponsors.

- Require PBMs to disclose an unredacted contract with the rebate aggregator.

- Require PBMs to be pay fees to rebate aggregators for their services but such fees should not come from drug manufacturer rebates.

- Require PBMs to agree to rebate audits conducted by plan sponsors and/or third-party auditors at plan sponsors’ choosing.

- Require PBMs to report claims-level data on rebates collected on claims paid by pan sponsors.

- As part of the PBM contracts, plan sponsors should:

Pharmacy Direct and Indirect Remuneration Fees

As a result of a 2014 CMS rule change that went into effect in Plan Year 2016, PBMs have developed shrewd and calculated methods of financial engineering, maximizing their revenue at the expense of the patient, the Medicare Part D Program, and providers. This was accomplished through pharmacy direct and indirect remuneration fees, or “DIR fees.” DIR fees are typically post point-of-sale fees ranging from 1.5% to 11% of a drug’s list price assessed by PBMs upon network pharmacy providers, typically three to six months after the provider has dispensed the medication.

The concept of DIR fees arose out of Medicare Part D coverage for prescription drugs. Part D plan sponsors and Medicare Advantage plans offering drug coverage are paid by the government based on the actual cost for drug coverage. The actual cost is based on the Part D plan sponsor’s “negotiated price,” which is then used as the basis to determine plan, beneficiary, manufacturer (in the coverage gap), and government costs during the course of the payment year, subject to final reconciliation following the end of the coverage year.

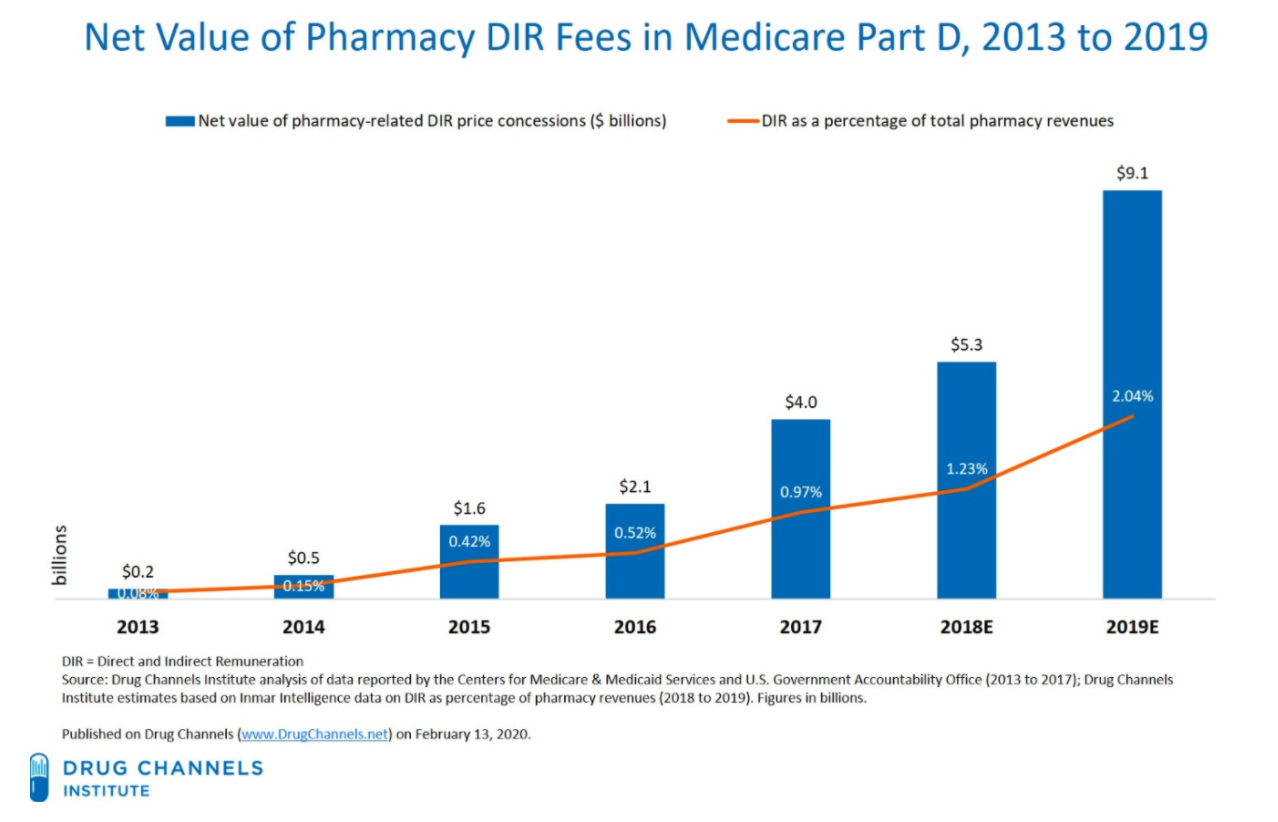

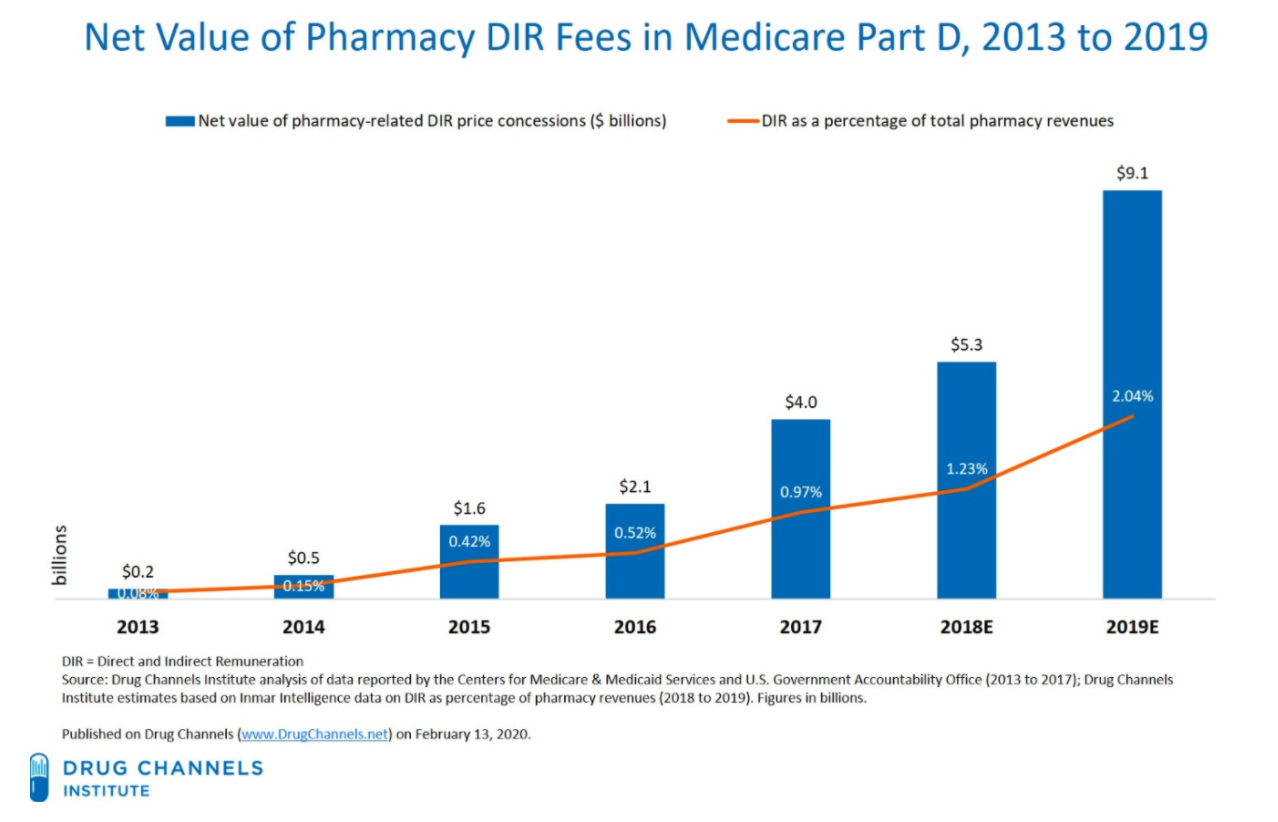

Unfortunately, very few pharmacy price concessions have been included in the negotiated price at the point of sale. All pharmacy and other price concessions that are not included in the negotiated price must be reported to CMS as pharmacy DIR. As employers and plan sponsors are demanding a greater share of the PBM rebates, and as those rebates have been threatened with regulation by state and federal lawmakers, PBMs have gone “downstream” to make up for any rebate revenue shortfalls by assessing DIR fees on pharmacy providers. In fact, DIR fees categorized as pharmacy price concessions have increased 45,000 percent between 2010 and 2017, and have hit a whopping $9.1 billion in 2019.

Figure 6. Explosion of Pharmacy DIR from 2013 to Present

PBMs purport to pass a large portion of DIR fees to their plan sponsor clients, especially Part D plan sponsors – ironically, many of which are under the same corporation as the PBMs (e.g., CVS Caremark, one of the nation’s largest PBM, and SilverScript, the nation’s largest Medicare Part D plan sponsor, are both owned by CVS Health). However, no study has been conducted to match the deductions from pharmacy remittances for “DIR” with the DIR reported to CMS. Unfortunately, CMS cannot even perform such an audit today, as it does not require plans to submit DIR collected from each pharmacy, but rather requires DIR to be reported by drug, on an NDC number basis.

Even if pharmacy DIR fees are reported accurately, Medicare risk corridors allow a Part D plan sponsor that spends less than its bid estimate of costs to keep all savings up to 5% and a portion of those savings thereafter, which, in practice, allows PBMs and Part D plan sponsors to retain the vast majority of DIR fees collected. Thus, PBMs and Part D plan sponsors financially benefit from DIR fees.

Worse yet, DIR fees on expensive specialty drugs are typically calculated as a percentage of a drug’s list price. As such, DIR fees provide another incentive for PBMs to keep drug list prices high – high list prices yield not only larger rebates, but also larger DIR fees. As such, over the past several years DIR fees have become a larger percentage of the overall revenue that PBMs and Part D plan sponsors receive. Simply put, PBMs are making their money one way or another — rebates or DIR fees from pharmacy providers.

More problematic than the growth of DIR fees is the manner in which DIR fees are assessed on providers, especially community oncology practices. These fees are charged against community oncology practices based on their performance in a number of primary-care focused “quality metric” categories, which are totally unrelated and irrelevant to the cancer patients these practices treat. As a result, these community oncology practices have no meaningful ability to influence their performance scores – with no ability for upside – and such fees amount to nothing more than extortion from practices. Given the market clout of the top PBMs in terms of the percentage of prescription drugs they manage, community oncology practices simply have to pay these DIR fees to stay in network, lest they lose the ability to provide dispensing services to their patients.

These DIR fees are assessed after the point-of-sale. While they are sometimes recouped as soon as PBMs reimburse providers (i.e., extracted from initial reimbursements), in most cases DIR fees are assessed months after patients receive their medications. The total amount of DIR fees assessed on providers may not be known by providers until more than a year after a drug has been dispensed, as some PBM contracts create the potential for a partial or total refund of DIR fees (though a total refund is practically unobtainable).

DIR fees increase patients’ cost sharing responsibilities because patient out-of-pocket costs are based on an artificially inflated list drug prices at the point-of-sale; thus, in the case of Medicare patients, prematurely pushing them into the Medicare Part D “donut hole.” The cost of DIR fees also shifts the burden of drug costs to the federal government as more patients are prematurely pushed into the catastrophic phase of the Medicare benefit, resulting in higher financial contribution by the Medicare program. Ultimately, DIR fees weakens the overall benefit of the Medicare insurance benefit intended to provide health care coverage for our nation’s oldest and most vulnerable citizens.

Finally, DIR fees extracted from reimbursement to providers often results in drugs reimbursed below drug acquisition cost. Some speculate that this is yet another strategy by PBMs to ultimately drive pharmacy providers out of business so that the PBMs can take over the business with their retail, specialty, or mail-order pharmacies.

PBMs are able to effectively “extort” DIR fees due to their size and hegemony. As of 2018, three companies – UnitedHealth, Humana and CVS Health – covered over half of all Medicare Part D patients. Pharmacy providers do not have a meaningful choice but to accept the terms being provided to them – rejecting just one Part D plan could mean losing out on being able to service nearly a quarter of their Medicare Part D patients. PBMs know the power they hold and use it to its fullest extent.

5.1 Who is Impacted?

The expansion of DIR fees has had a substantial negative impact on both Medicare beneficiaries and the program as a whole. As confirmed in recent CMS studies, DIR fees ultimately shift financial liability from the Part D plan sponsor to the patient, then ultimately to the federal government, through Medicare’s catastrophic coverage phase. The shifting of financial liability away from the Part D plan sponsor and to Medicare and the patient is even more pronounced with specialty medications, such as oral cancer medications.

5.1.1 Harm to Patients

The primary harm to patients from DIR fees is that patients’ out-of-pocket costs are higher because they are based on list drug prices. Once again, PBMs have a vested financial interest to have drug list prices as high as possible as DIR fees are assessed as a percentage of the list prices for expensive specialty drugs. Medicare Part D patients find themselves paying more for their medications because they pay increased copayments and coinsurance on inflated point-of-sale list prices, which do not reflect the after-the-fact price adjustment in DIR fees that the PBM is clawing back from the pharmacy provider.

The use of DIR fees by PBMs has degraded the quality of the Medicare Part D benefit available for beneficiaries, all the while providing an additional lucrative revenue source for PBMs and affiliated Part D plan sponsors. It has shifted the benefit of the Medicare Part D program from those who rely on it for drugs, to those that do not use it, in the form of lower (or zero dollar) premiums. Meanwhile, DIR has put upward pressure on drug expenditures for those that use the benefit. Studies conducted by CMS have concluded that DIR fees increase out-of-pocket costs for Medicare patients at the point of sale.

Consider for example, that Medicare Part D beneficiaries’ cost sharing is based on the PBM-determined rate at the point-of-sale. DIR fees are by definition not assessed at the point of sale. Thus, the patient’s copayment or coinsurance that is based on the price at the point-of-sale is artificially inflated. CMS similarly concluded that DIR fees cost patients money, noting “[w]hen pharmacy price concessions and other price concessions are not reflected in the negotiated price at the point of sale (that is, are applied instead as [Direct and Indirect Remuneration] at the end of the coverage year), beneficiary cost-sharing increases.”

Likewise, up until the end of the 2020 plan year when the “donut hole” existed in the Medicare Part D Program, DIR fee programs pushed patients through the coverage stages much faster. Within the donut hole, patients pay 25% of the drug cost based on the (inflated) list price at the point-of-sale. The concern that patients continue to foot the bill for increased costs is not hidden from scrutiny as a group of 21 U.S. Senators urged HHS to address DIR fees because “beneficiaries face high-cost sharing for drugs and are accelerated into the coverage gap (or “donut hole”) phase of their benefit.”

In addition, despite PBMs’ purported justifications for such programs, DIR fees have not benefitted the quality of Part D plans offered to Medicare beneficiaries. For example, SilverScript had a 4.0 Star Rating from Medicare in 2018 (based on 2017 data), but saw its score drop to a 3.5 Star Rating in 2019 despite the widespread usage of DIR fees. At the same time, as the impact of DIR fees has increased dramatically since 2016, patients have also been impacted by diminished access to care as providers facing decreased net reimbursement are forced out of business, forcing patients to receive services from pharmacies owned by or affiliated with the very PBMs and Part D plan sponsors extracting DIR fees (see, Section 6, infra).

5.1.2 Harm to Plan Sponsors

Just as DIR fees negatively impact patients, PBM-Imposed DIR fees shift costs away from Part D plan sponsors, while increasing the costs to the Medicare program (and in turn, the taxpayer) for catastrophic coverage and subsidy payments. As mentioned, when a Medicare beneficiary is pushed through the benefits tiers and reaches the “catastrophic coverage” stage, the cost of services shifts to 80% paid by Medicare, while only 15% paid by the plan sponsors. The government covers these costs in part by turning to the reinsurance marketplace. From 2007 through 2018, a period similar to when CMS saw DIR fees from pharmacy price concessions increase by more than 45,000 percent, reinsurance costs of Medicare soared by 411%. Part D plan sponsors and their PBMs have a financial incentive to move Medicare beneficiaries into the catastrophic phase of coverage, to the detriment of the taxpayer.

In fact, the National Community Pharmacists Association (NCPA) commissioned a report by Wakely Consulting Group, LLC to estimate the cost savings that would occur if congress prohibited retroactive reductions in payments by Part D plan sponsors in the form of DIR fees. Wakely Consulting Group, LLC found $3.4 billion in Part D payments over a nine-year period if these fees were prohibited.

Unfortunately, the harm from DIR fees goes beyond the Medicare program and American taxpayers. Like rebates, DIR fees have the effect of driving up the cost of drugs, through higher list prices. From 2013 to 2019, DIR fees rose from $229 million to an estimated $9.1 billion. Most striking, however, is that DIR fees now account for more than 18% of all Medicare rebates received by Part D plans. This increased reliance on DIR fees relative to drug rebates, both of which are tied to the list price of drugs, highlights the upward pressure DIR fees have placed on list prices for drugs. During this same period, drug list prices grew between 10-15% per year. Meanwhile, net prices have been relatively flat throughout this time period. These inflated list prices are felt by all plan sponsors – especially employers and state Medicaid programs – who do not receive any of the supposed benefits of DIR fees (such as lowered premiums).

PBMs have used their consolidation in the marketplace to use DIR fees and rebates in concert, fueling higher drug prices, while adversely impacting cancer care.

5.1.3 Harm to Providers

To say that DIR fees have had an adverse impact on providers is an understatement. DIR fees decrease pricing transparency creating uncertainty as to the true real reimbursement rates for drugs, very often driving reimbursement rates below the providers’ acquisition cost of drugs (see, Section 8, infra).

The metrics utilized by PBMs in implementing DIR fee programs are typically completely inapplicable to community oncology practices. Specifically, community oncology practices dispense primarily (and almost exclusively) specialty medications for cancer patients. As such, they have virtually no ability to influence their performance based on PBMs’ “quality metric” categories measuring patient drug adherence relating to cholesterol, heart disease, and diabetes medications, which are relevant to dispensing general medications, not specialty drugs.

Worse yet, adherence-based metrics are particularly problematic and in cases not only wholly inapplicable in treating cancer patients, but also may be very dangerous. Community oncologists are extremely vigilant about monitoring their patients’ cancer medication regimens and may temporarily discontinue or “hold” medications until a patient’s status returns to an acceptable level, especially relating to adverse drug side effects. The period during which the medication is “held,” or therapy is temporarily discontinued, is wrongly and obtusely measured by the PBM as a lack of adherence in one of the few areas where the community oncology practices may be measured, ultimately causing the community oncology practices’ performance to decrease, and the DIR fee assessment to subsequently increase.

Consider, for example, Imbruvica (ibrutinib), which is dispensed by many community oncology practices to treat mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Studies have shown that Imbruvica tends to cause hematologic effects such as neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in MCL and CLL. If these adverse events occur at certain levels, the standard of care – as articulated directly by the FDA-approved package insert – is to hold the medication until the patient’s lab values return to normal ranges. This can happen in as many as 46% of cases, resulting in discontinuing the patient’s medication for up to a month. If community oncology practices are required to continue to dispense this drug, it will result in additional (and avoidable) costs to Medicare for the discontinued fills, as well as potential harm to the patient (along with potentially increased costs to Medicare for associated medical costs).

Further, due to the high cost of specialty drugs, and in particular, oncology medications, any small change in perceived adherence rates due to the purposeful physician-directed temporary discontinuation of therapy results in unreasonably low reimbursement rates. Many PBMs justify their DIR fee programs as being designed to influence providers to deliver better care to patients in their Medicare Part D networks. On that clinical basis, if community oncology practices were to be “influenced” by the PBMs’ DIR fee metrics by adhering to a medication when the FDA-approved label calls for the therapy to be held, patients would suffer. As such, community oncology practices are often left without any meaningful way to impact PBMs’ so-called “quality metrics” and improve their DIR fee performance.

Ultimately, community oncology practices have no way out. For them, due to the clout and market leverage of PBMs, DIR fees are simply a form of extortion that community oncology practices are forced to pay.

5.2 What Does the Law Say?

The most directly applicable legal principles relating to pharmacy DIR fees are found in the federal Any Willing Provider law. Within the federal Any Willing Provider law, CMS expressly recognized that unreasonably low reimbursement, which often result after accounting for DIR fees, violates the federal Any Willing Provider law. As it relates to the methodologies being used to assess DIR fees, performance criteria, and the manner in which PBMs and Part D plan sponsors are using those programs must also be reasonable and relevant. For community oncology practices, performance criteria that they are unable to influence or performance criteria that does not reasonably measure optimal cancer care can run afoul of the federal Any Willing Provider law.

In addition to explicit statutory language and CMS guidance, many of these principles are incorporated within, and apply directly to, the contract between PBMs and community oncology practices. PBM contracts include explicit obligations that the PBMs will comply with federal code, statues, rules, and CMS guidance, including but not limited to the Medicare Part D Provider Manual. These contractual obligations are not included in the contract with pharmacies by choice, but rather federal law requires these terms to be included in the contract between CMS and plan sponsors, and in contracts with their first tier entities (including PBMs, and in contracts between PBMs and pharmacy providers). This creates affirmative obligations on PBMs to comply with these laws, as well as the ability for pharmacy providers to directly challenge PBMs for breaches of contract when PBM actions do not comply with federal law.

In January 2022, CMS introduced a proposed Final Rule that would alter the way PBMs and Part D plan sponsors are required to report DIR fees. In particular, CMS has proposed that PBMs and Part D plan sponsors report the lowest possible reimbursement to pharmacy providers (inclusive of all potential DIR fees) as the “negotiated price.” While this proposed rule (if finalized) could have the result of removing the financial incentive for PBMs and Part D plan sponsors to institute retrospective DIR fees, it does little to protect pharmacy providers against unreasonably low reimbursement rates or wholly irrelevant “quality” metrics when assessing DIR fees.

5.3 What Can Be Done?

- Legislative Solutions

-

- Federal legislation should be enacted requiring that any DIR fee program (i) be tied to relevant quality programs to the specialty being measured; (ii) actually measured on an individual pharmacy level; (iii) provide equal opportunity for upside performance (i.e., not just a way for PBMs to “rig” the program to always measure downside performance resulting in DIR fees extracted from the provider); and (iv) require that DIR fees be applied equally and fairly across all network pharmacies, specifically including PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies).

- Federal legislation should require that all pharmacy price concessions, including DIR fees, be included in the negotiated price at point-of-sale.

- Federal legislation should give CMS greater latitude in regulating the reimbursement structure between Part D plan sponsors and pharmacy providers.

- Regulatory

-

- CMS should issue regulation providing “guard rails” on what constitutes reasonable and relevant terms and conditions, and clarify that whether given terms are “reasonable” or “relevant” can be adjudicated in a private contractual dispute between Part D plan sponsors/PBMs and pharmacies.

- CMS should initiate complaints against Part D plan sponsors and PBMs who have failed to pass on negotiated prices to patients at the point-of-sale, when DIR fees were known or knowable (i.e., the PBM maintained a minimum range of DIR fees that were to be assessed against every pharmacy no matter what).

- CMS should initiate complaints against Part D plan sponsors and PBMs who have not paid providers based on reasonable and relevant terms and conditions, including through unreasonably low reimbursements, or irrelevant performance criteria.

- CMS should require reporting of pharmacy DIR fees by both NDC number and pharmacy National Provider Identifier (NPI) allowing for full end-to-end audits of the flow of money from pharmacies to the Medicare program. The results of these audits should be made available to the public.

Restrictive Networks, Credentialing Abuses, and Artificial Barriers of Entry

PBMs maintain a monopoly-like grasp on the industry, the natural result of which is the inability of patients to freely choose a provider based on his or her personal health care decisions, as opposed to the mandates of his or her PBM. As noted previously, only three PBMs process more than three-quarters of all prescription claims: CVS Health, Express Scripts, and OptumRx, while five PBMs process over 80% of all prescription claims. Each of the three major PBMs share common ownership with a major insurer and in turn with a mail-order and/or specialty pharmacy. These vertical, integrated relationships allow the PBMs to control the pharmaceutical supply chain, and erect superficial barriers to entry or even outright exclude entire classes of potential pharmacy providers.

This is particularly pronounced in the context of cancer care, where the introduction of new oncology therapies over the past several years, specifically, oral treatments for cancer and related conditions, presents new challenges for patients, plan sponsors, and providers alike. Between 2017 and 2019, there have been over twenty-four new oral cancer medications introduced into the marketplace. In 2020 alone, ten new oral oncolytics were approved by the FDA. As it stands, oral oncolytics make up 25% to 35% of cancer medications in development, making it likely that over the next several years, oral therapies will encompass an indispensable component of any treatment plan for cancer patients. While traditional chemotherapy infusion therapy that is “administered” is covered under a patient’s “medical” benefits, oral oncolytics that are “dispensed” are being shifted to the patient’s “pharmacy” benefits, managed by PBMs. Unlike chemotherapy administered in the clinic setting, the advent of oral oncolytics have given the PBMs a tremendous new opportunity to control cancer care and divert prescriptions and profits to themselves.

These new oral cancer medications can be extremely expensive, often ranging more than $10,000 per month. This is what is attracting PBMs, and as a result, PBMs have attempted to use their market size and leverage to limit dispensing of oral oncolytics through certain specialty and/or mail-order pharmacies, most often their own or affiliated pharmacy.

PBMs use several different tactics to maintain their control over where patients receive their care. The first and foremost of these is creating restricted networks, blocking access to any provider that is not affiliated with their PBM. In these instances, the PBM will contend that the network is “closed” or that there is no “network,” and thus, pharmacy providers are not even given the opportunity to apply for network admission. This occurs more frequently in the commercial insurance space involving employer-sponsored plans, but can also involve Medicaid managed care programs, where the PBM will require patients to receive their cancer medication from the PBM’s wholly-owned or affiliated pharmacy, and no one else. This is anticompetitive conduct – pure and simple – where patients are trapped into using one particular provider not based on the quality of care provided by that provider but based on the financial arrangements and the corporate affiliation between the pharmacy provider and the PBM and/or health insurer.

A related, but slight variation of this tactic is to restrict access to certain classes of providers (i.e., retail pharmacies), while excluding wholesale other classes of providers (i.e., dispensing physician practices). For example, beginning in early 2016, CVS Caremark espoused a self-serving stance that dispensing physician practices were now to be deemed “out-of-network” and no longer able to participate in Medicare Part D networks. This would have the effect of dramatically interrupting the ongoing relationship between treating oncologists and their patients. CVS Caremark later backtracked on this position and began allowing “grandfathered” dispensing physicians (i.e., those that previously held a contract with the PBM) to continue in-network, but delayed the processing of any new, non-grandfathered dispensing physician practices. In another instance, in January of 2018, Prime Therapeutics (Prime) – the PBM owned by a consortium of approximately twenty-two Blue Cross Blue Shield plans – announced that it would no longer accept any new dispensing physicians into its pharmacy networks on the alleged basis of “fraud, waste, and abuse” concerns and a commitment to maintaining to compliant networks. Without providing any further details, Prime claimed that Dispensing Physicians did not adhere to Prime’s Provider Manual. This trend expanded to existing in-network dispensing physicians actively servicing patients when, recently, Prime announced that it would also terminate existing, or “grandfathered” dispensing physicians from its networks. Despite having credentialed, contracted, and paid dispensing physicians as “in-network” Medicare Part D providers for over a decade, Prime seemingly unilaterally took the position that dispensing physicians are now considered “out-of-network providers” under Medicare Part D. Like wholesale network exclusion, these practices disadvantage vital providers while allowing PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies to capture a greater share of prescription volume.

Even in instances where a PBM nominally allows a community oncology practice to apply for network participation, the PBM can still place other barriers in the way of providers being able to service their patients by imposing onerous credentialing processes. For a community oncology practice to service patients within a PBM’s network, PBMs require that the provider adhere to specific and extremely onerous, credentialing requirements, including the requirement that the provider maintain certain accreditations. These conditions are made even more onerous where PBMs delay the review of credentialing applications (seemingly with the intention to avoid admitting these providers), enact credentialing applications with terms and conditions designed to keep out providers (rather than ensuring the quality of providers) or allow participation but at rates so low that reimbursement may not even cover the acquisition cost of a drug. These obstructionist policies harm patients, degrade the quality of prescribers and benefit only PBMs that are incentivized to continue to these illegitimate practices.

Finally, even when a community oncology practice has ultimately been admitted into a PBM’s network, PBMs continue to utilize other tactics to drive patients away from community oncology practices, and towards PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies. This includes tactics such as patient slamming and claim hijacking (see, Section 7, infra), misleading communications aimed at steering patients to PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies, and creating patient incentives for patients (such as lower copays, larger days’ supply or free products/services) to utilize preferred PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies. PBMs also utilize other tactics, such as abusive auditing practices (i.e., requiring the production of thousands of pages of documentation to support claims billed) and terminating providers without cause or on pretextual bases (i.e., that they only dispense one class of medications).

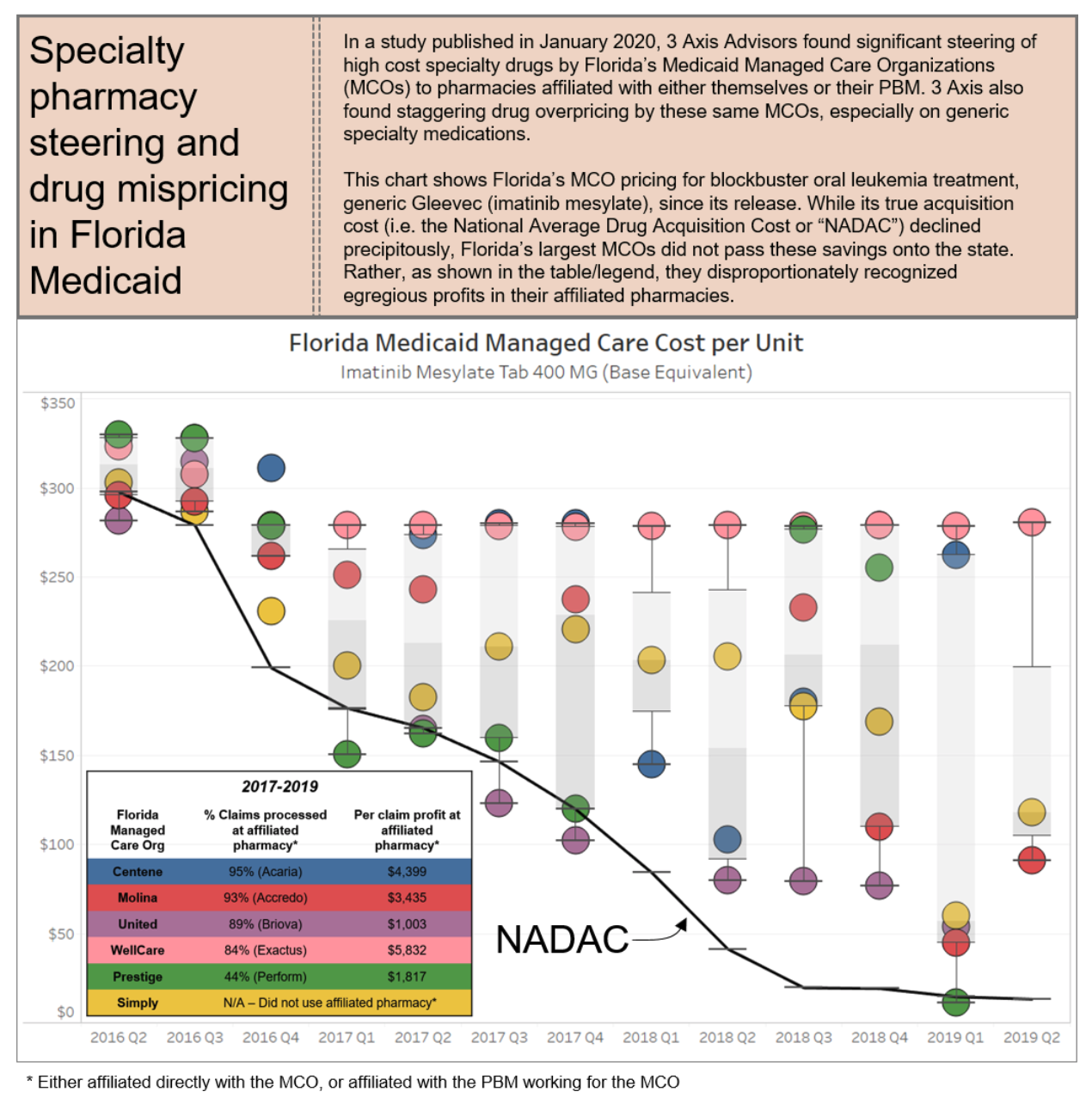

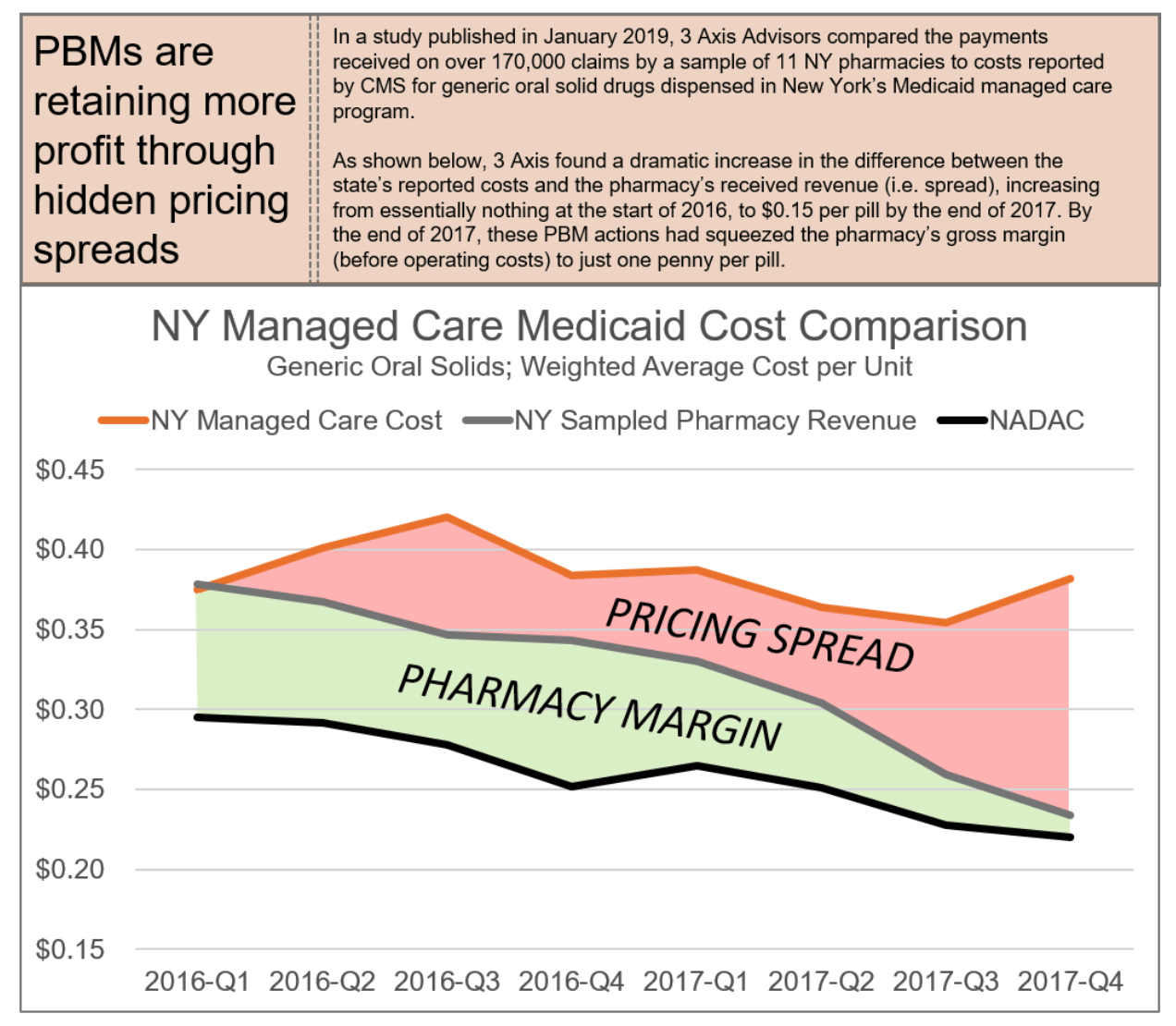

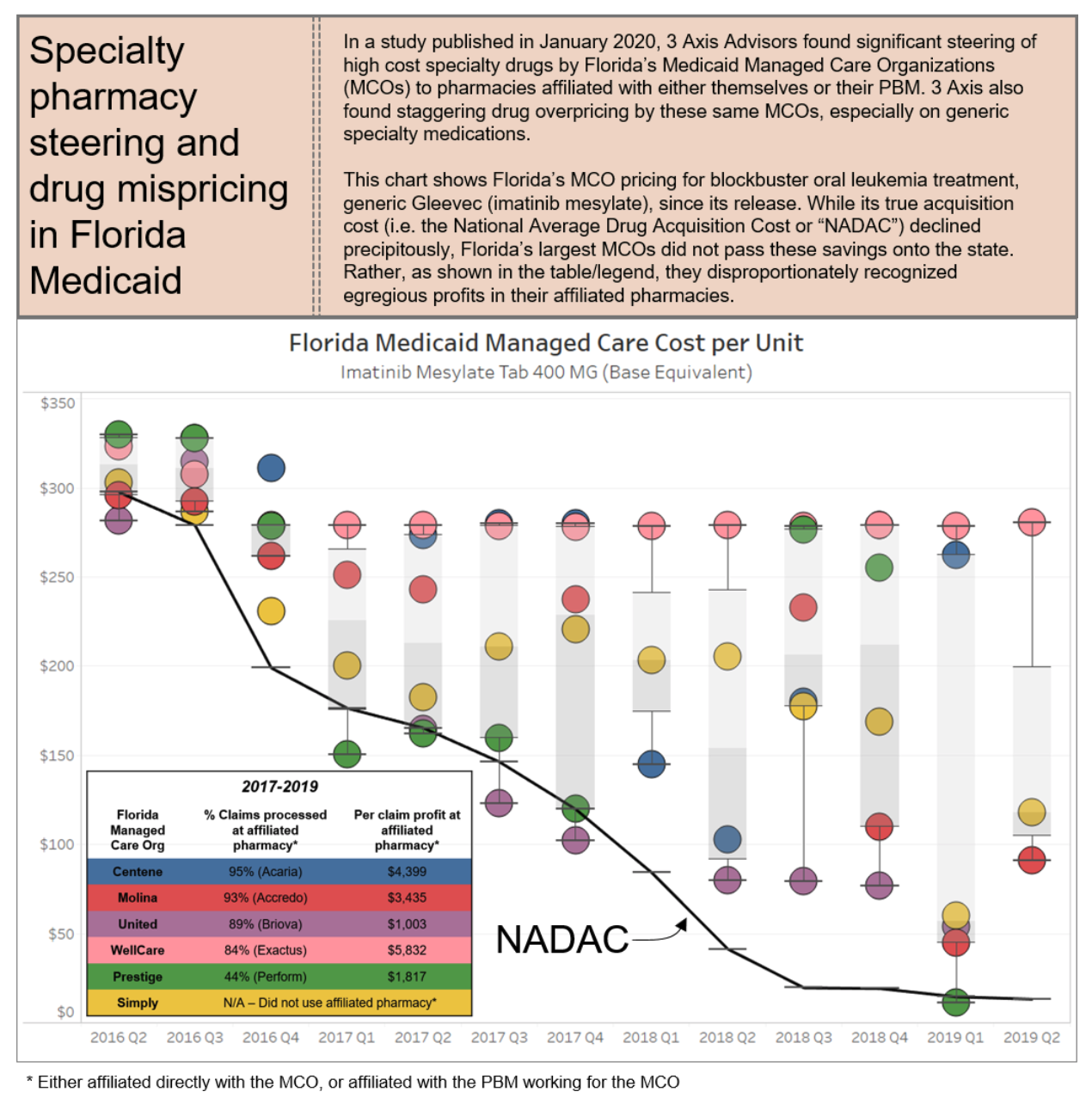

PBMs employ these tactics to maintain their oppressive market dominance. But at the same time, in a vicious cycle, these tactics are themselves the consequence of the horizontal and vertical consolidation within and between insurance and PBM markets, which has created merged entities with such oppressive power that it a virtual chokehold on community oncology practices and pharmacy providers. The result of these tactics is that patients are steered away from receiving care at their community oncology practices, and forced to receive care from PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacies. This is not only without regard to the impact on patient care and outcomes, but as the chart below demonstrates, only continues to prop up higher drug prices and charges.

6.1 Who is Impacted?

The overall lack of industry standards and oversight in the PBM credentialing sphere has led to arbitrary denials and lengthy, costly application processes, that ultimately have a negative impact on a community oncology practice’s ability to focus on patient care. Instead of allowing community oncology practices to enter into their networks, PBMs attempt to limit the dispensing of oral oncolytics through their own specialty pharmacies, leading to poor patient compliance and adherence to life-saving treatments, causing the quality of cancer care to suffer.

These tactics have had negative impact all across the spectrum, affecting patients, health care payers (including Medicare, Medicaid, employers and taxpayers), and providers.

6.1.1 Harm to Patients

These exclusionary practices – whether they be unreasonable barriers to entry or outright exclusion of certain classes of providers – result in serious harm to patients, specifically those who are seeking the services of community oncology practices that have been excluded from a PBM specialty network. For one, these exclusionary practices destroy existing patient-provider relationships. In early 2016, when CVS Caremark undertook re-interpreting longstanding CMS regulations, it did so in such a way as to effectively cut out physicians from continuing to dispense medications to their existing Medicare Part D patients. PBMs have no regard for the continuity of these vital health care relationships and their impact on patients’ well-being and outcomes.

This is critical, as patients are more likely to raise certain questions or concerns about their medications, when these medications are dispensed by community oncology practices. To strip patients, who are facing serious life-threatening diseases, of that important patient-provider relationship could result in serious patient harm. This also has the effect of decreasing medication adherence, which would further affect patients, especially those undergoing life-saving treatments at community oncology practices.

The ultimate outcome of creating restricted networks or excluding entire classes of providers, namely, that patients are essentially required to obtain medications at a PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacy. It is well-documented that when the PBM-owned or affiliated pharmacy is responsible for filling the patients’ prescriptions, it results in worse care. The near-monopolistic control of the network, combined with the lack of patient choice, remove any checks and balances on the quality of the care being provided.

Consider, for example, a patient battling cancer was denied life-saving medications by a PBM due to the PBM being unwilling to enter medications into its computer system. In another example, a patient had been diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome-positive + chronic myeloid leukemia and had been responding positively to “180mg” of a certain medication. However, according to the patient’s PBM, the medication had to come from the PBM’s mandated mail order specialty pharmacy instead of a pharmacy of their choice. Since the medication was not available in a single 180mg dosage form, the prescription clearly indicated that the patient was to receive a “100 mg tablet and an 80 mg tablet.” Instead, over the course of the next several months, the PBM pharmacy dispensed either a 100 mg tablet or an 80 mg tablet, but never both. Ultimately, the patient did not respond well to the lowered dosages of the medication. Finally, in a particularly disturbing example, a colorectal cancer patient was prescribed a common oral medication that had been on the market for nearly twenty years. The patient’s PBM mandated that the patient fill the prescription at a large, well-known specialty pharmacy, and the patient’s oncologist prescribed the medication to be taken in rounds with the following specific instructions: ‘two weeks on, one week off.’ The PBM mail-order pharmacy neglected to include the ‘one week off’ instruction on the label, and as a result, the patient ended up in the intensive care unit of a hospital.

Unfortunately, patients often do not have any ability or choice to switch their PBMs in order to have control over which pharmacy provider from whom they would like to receive service. PBMs who undertake these restrictive practices are typically selected by the patient’s employer (or sometimes by the insurance company selected by the patient’s employer). The patients are two, sometimes three steps removed from any part of the decision-making process. Since most patient get their health care coverage through their jobs, the only way a patient can exert any control over the network of pharmacy providers is to change jobs and hope that their new employer utilizes a different PBM’s network. But, in a world where three PBMs account for nearly 80% of the marketplace, the odds of getting a better PBM are slim to none.

The PBMs know the level of power that they wield. And their focus is on profits, not patients. Ultimately, given the acute focus on patient care inherent in community oncology practices, patients suffer when those providers are forced out of the space.

6.1.2 Harm to Plan Sponsors

In addition to patients, these exclusionary practices harm plan sponsors, such as Medicare and Medicaid, because they cause an artificial rise in the cost of specialty medication, particularly within the oncology space. Specifically, the exclusion of community oncology practices from PBM networks require more patients to utilize PBM-owned or affiliated mail-order and/or specialty pharmacies. This, in turn, leads to exponentially more waste of medication, causing increased costs to plan sponsors. Mail-order pharmacies, without proper access to patient outcomes, routinely dispense 90-day supplies of medications. In several instances, patients continue to receive medications despite their repeated requests to have the mail-order pharmacy cease sending medication, often due to a change in their course of treatment. In more tragic cases, the PBM mail-order pharmacies continue to dispense medications to the patient’s residence despite the patient having passed away, leading to the waste of unwanted, expensive medications.