CY 2023 Medicare Advantage and Part D Proposed Rule (CMS-4192-P)

Executive Summary

Over the past year, an alarming trend has emerged in the healthcare context that threatens to disrupt the entire delivery model for a large subset of our nation’s most vulnerable patients – seniors enrolled in the Medicare Part D Program receiving complex medications for live-saving treatments. This trend – unilaterally-imposed by vertically-integrated health plans and pharmacy benefits managers – jeopardizes patient access to these critical drugs. This trend is the advent of performance-based “DIR Fees.”

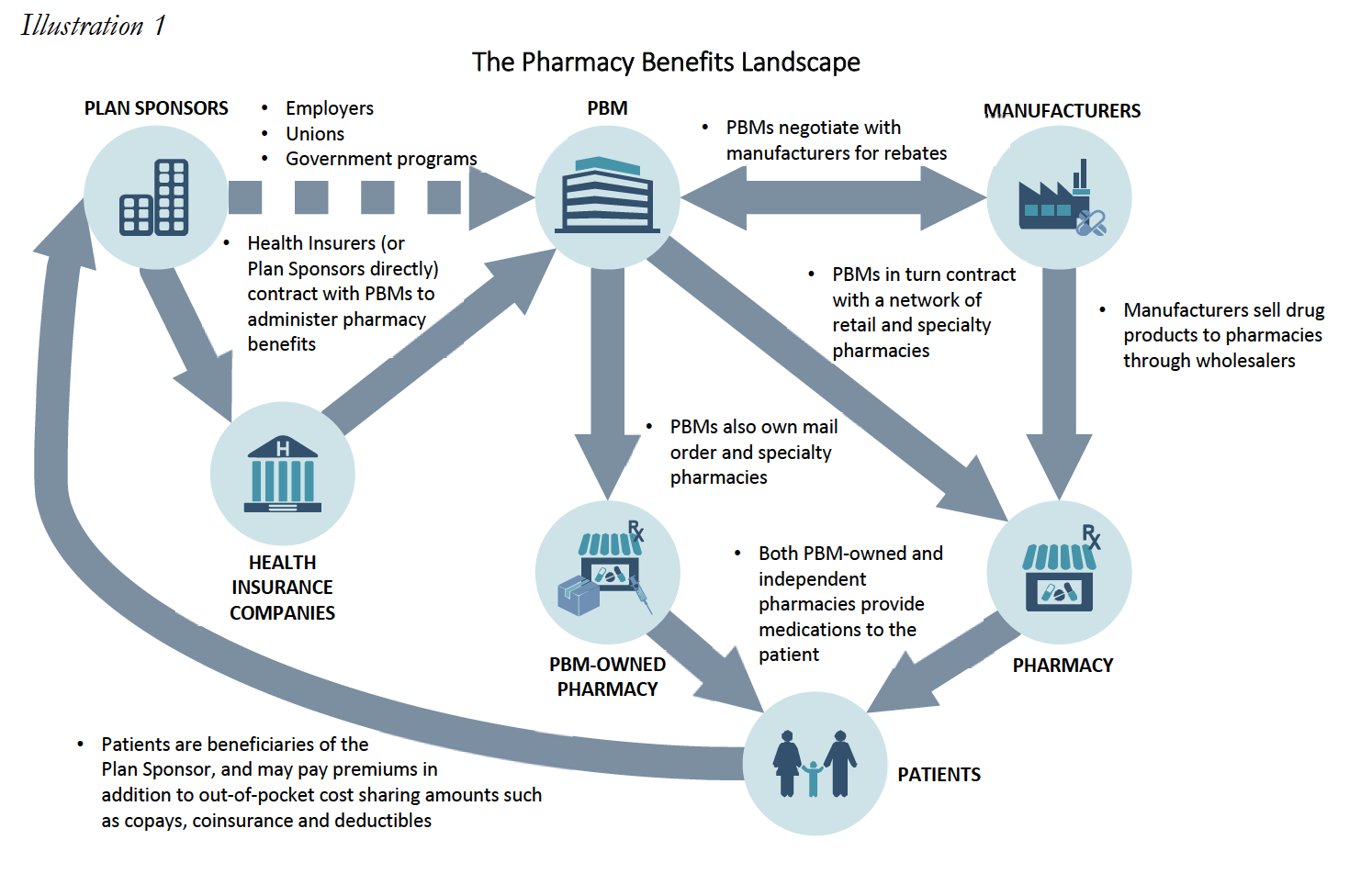

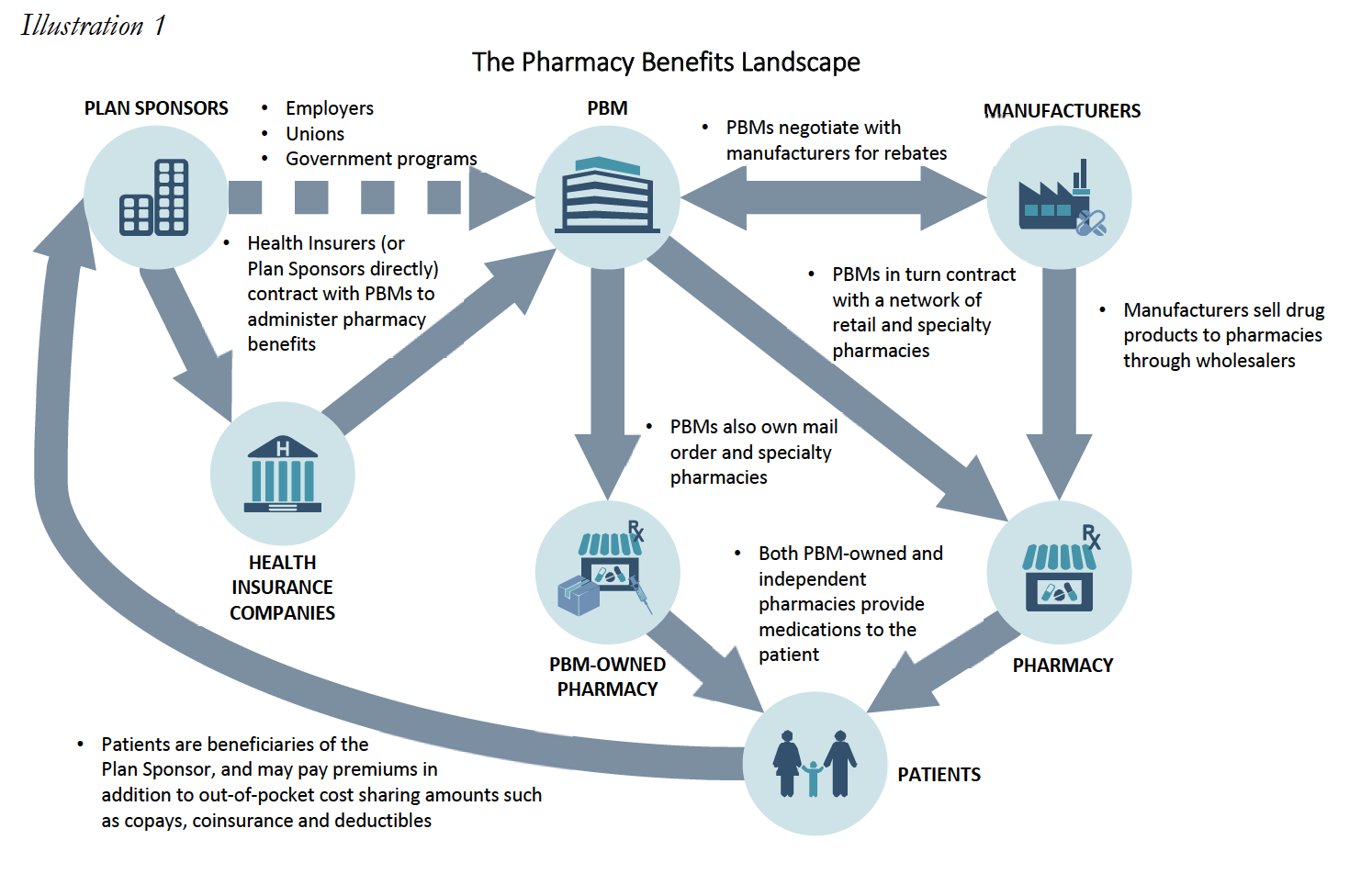

The management and administration of pharmacy claims in the United States is a process largely unfamiliar to the public. Unbeknownst to many, the administration of pharmacy claims is oftentimes not done by a patient’s insurance company, but is rather delegated by the patient’s insurance company to a pharmacy benefit manager, or “PBM.” These PBMs may consist of massive companies that act as middlemen between “Plan Sponsors,” such as health insurance companies and government programs, and healthcare providers, such as pharmacies. However, through a series or mergers and acquisitions the PBM industry’s power has grown tremendously, and with their power has come the implementation of policies that have caused shockwaves throughout the pharmacy industry. The focus of this White Paper is on one such policy, a policy which, if allowed to continue, will result in incalculable damage to the Medicare Part D program and, more importantly, Medicare beneficiaries.

In 2016, a significant change was noted in the administration of “direct and indirect remuneration” or “DIR” fees by select PBMs and plan sponsors against a plethora of pharmacies, including Specialty Pharmacies, that participate in Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D pharmacy networks. The concept of DIR is not new to Medicare. Indeed, DIR was a term that originated from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (“CMS”) in an effort to capture in the “actual cost” of a prescription drug and any post point-of-sale price concessions. However, beginning in 2016 select PBMs and Medicare Part D Plan Sponsors began assessing retroactive fees to pharmacies participating in Medicare Part D networks. These fees are charged against pharmacies based on their performance in a number of primary-care focused “quality metric” categories, which are totally unrelated and irrelevant to Specialty Pharmacies and specialty pharmacy patients. These “DIR Fees” have upended the pharmacy industry, clawing back the funds dedicated to the cost of comprehensive, coordinated patient care and support services, and stand to threaten the continued ability of Specialty Pharmacies participating in Medicare Advantage and Part D networks to provide patient-necessary services which ensure optimal clinical outcomes.

As a whole, the PBM industry’s assessment of DIR Fees is wholly improper. However, this White Paper focuses on a subset of pharmacies, known as Specialty Pharmacies, where the effect of DIR Fees has been far more disparate. Specialty Pharmacies predominately provide medications for people with serious health conditions which require complex therapies, including cancer, hepatitis C, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis. Due to the complexity of the medications, Specialty Pharmacies provide services well beyond simply providing prescription drugs to their patients, but rather offer a number of “high touch” services and also assist patients with special administration requirements (such as injectable medications or infused medications). The Specialty Pharmacy business model is critical to the healthcare system, as they provide services for oftentimes the sickest and most vulnerable portions of the patient population – Medicare beneficiaries. However, the Specialty Pharmacy business model is also the most susceptible to the negative impacts of DIR Fees.

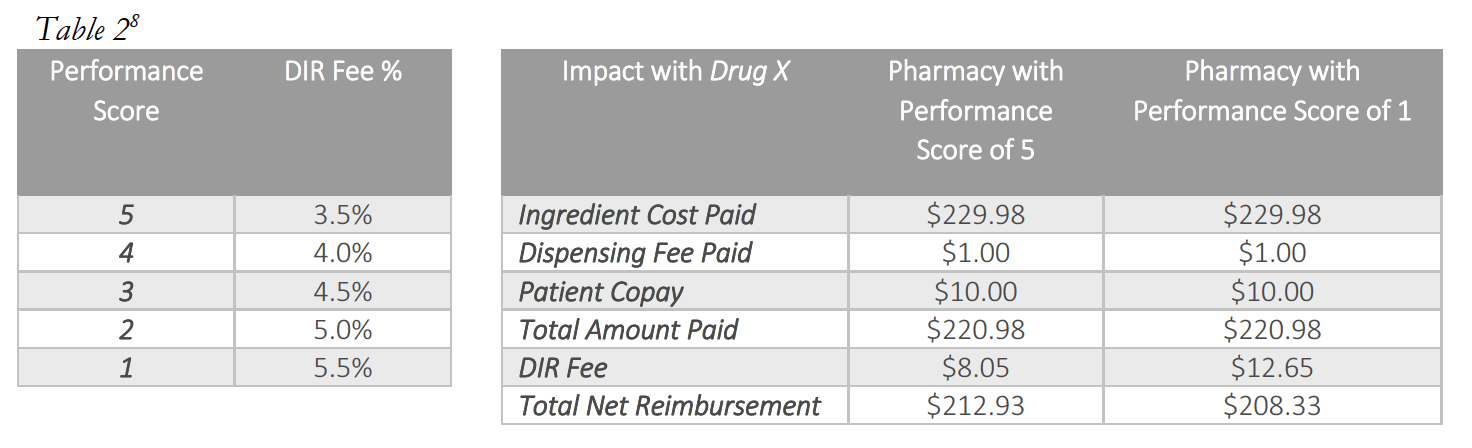

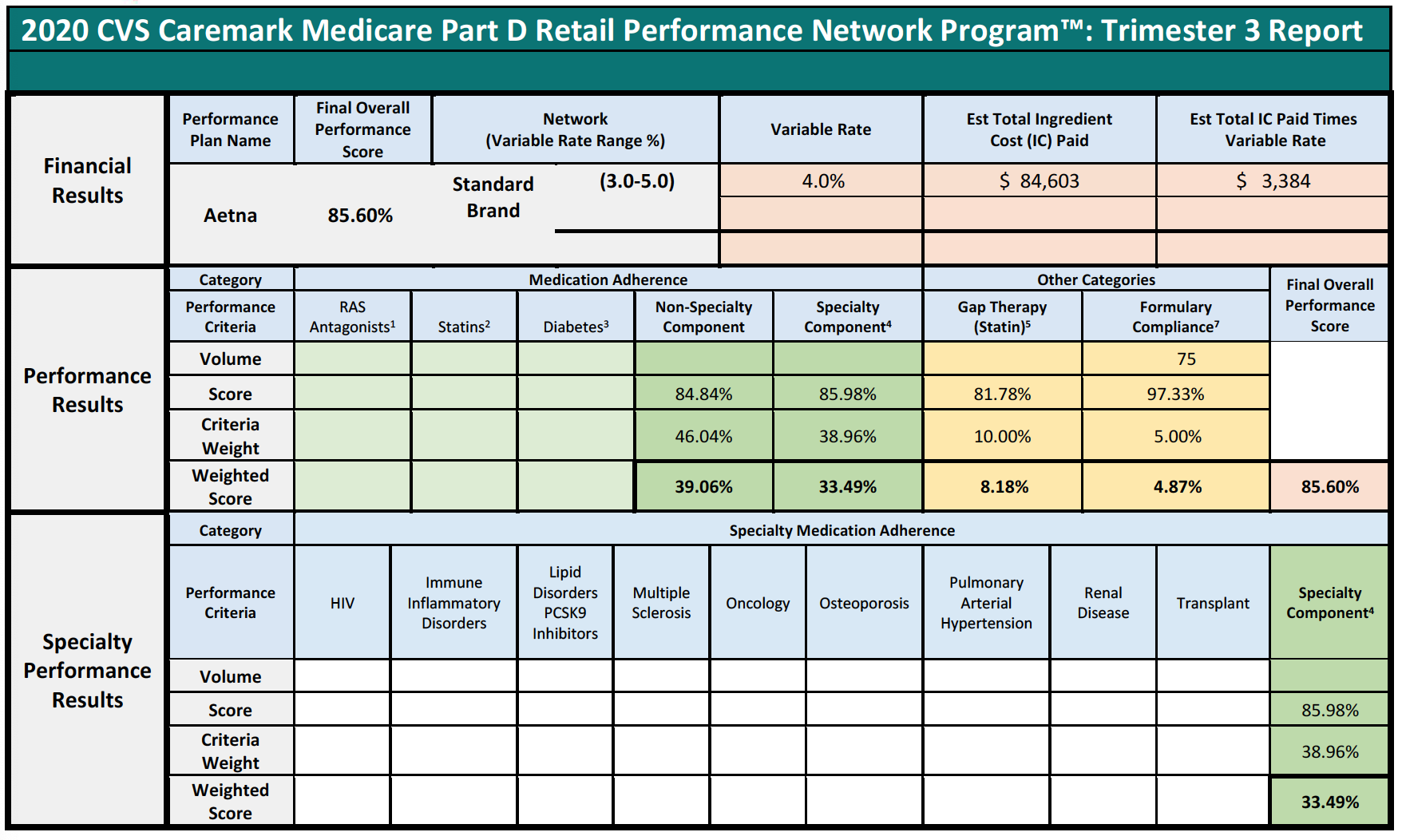

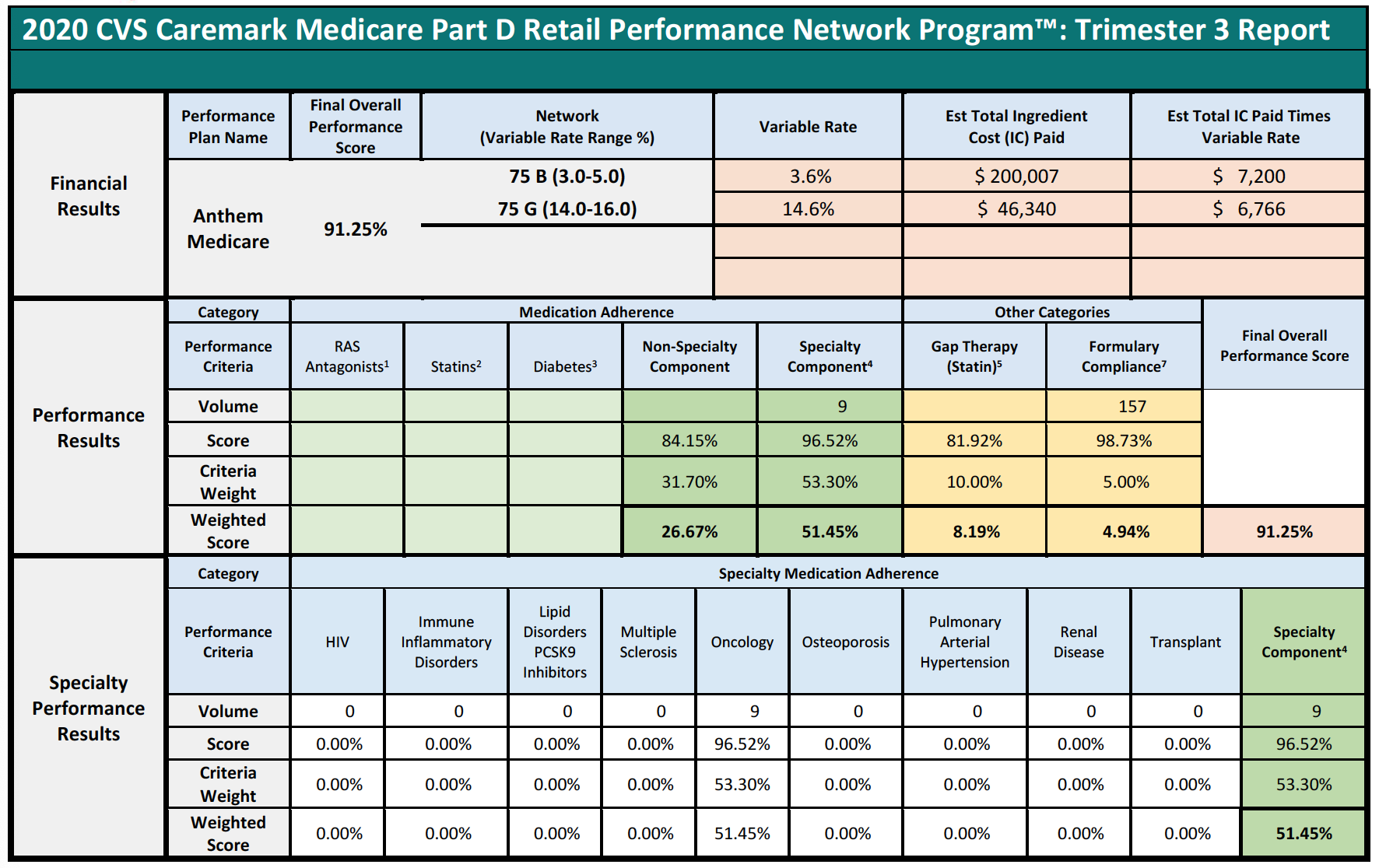

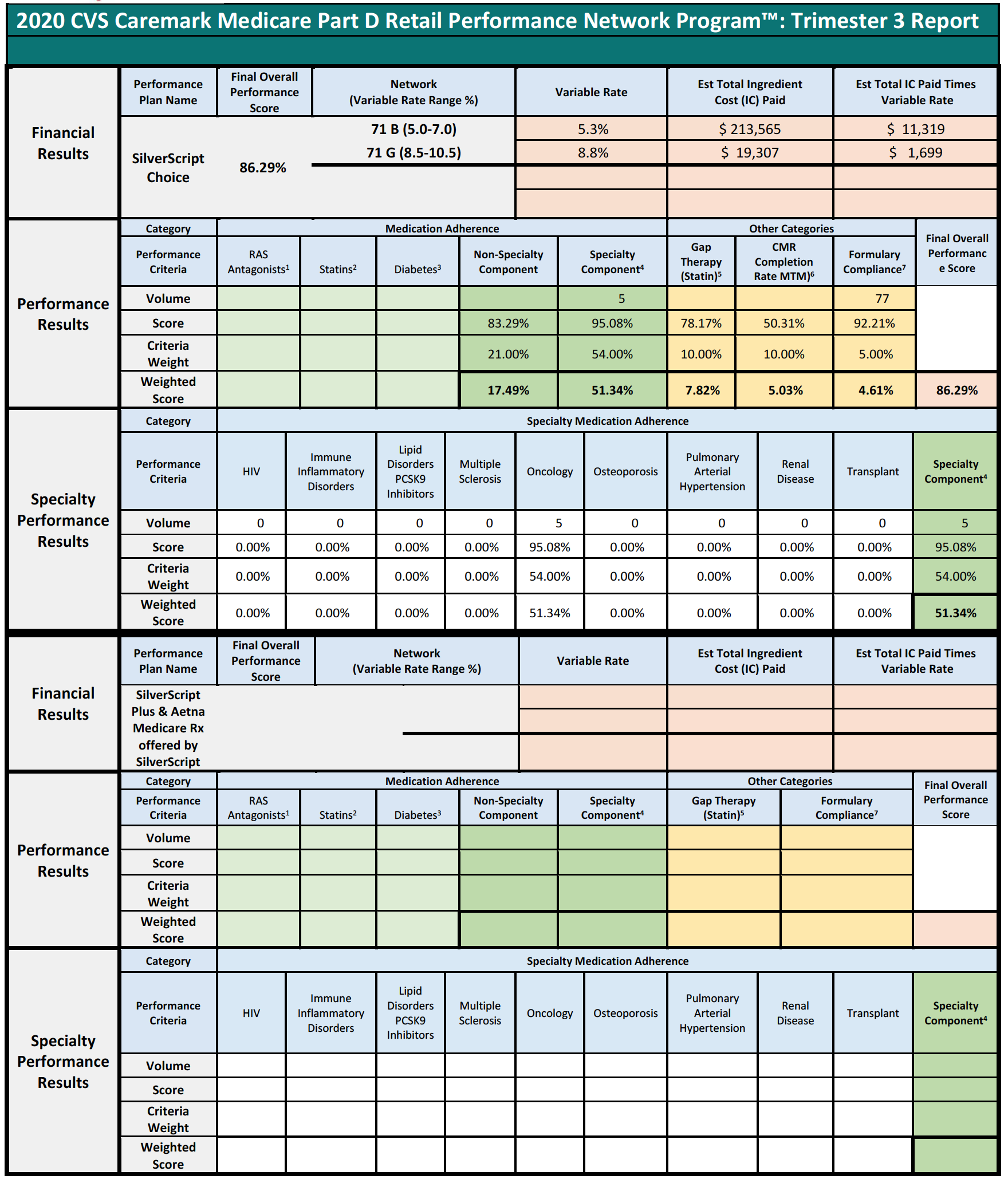

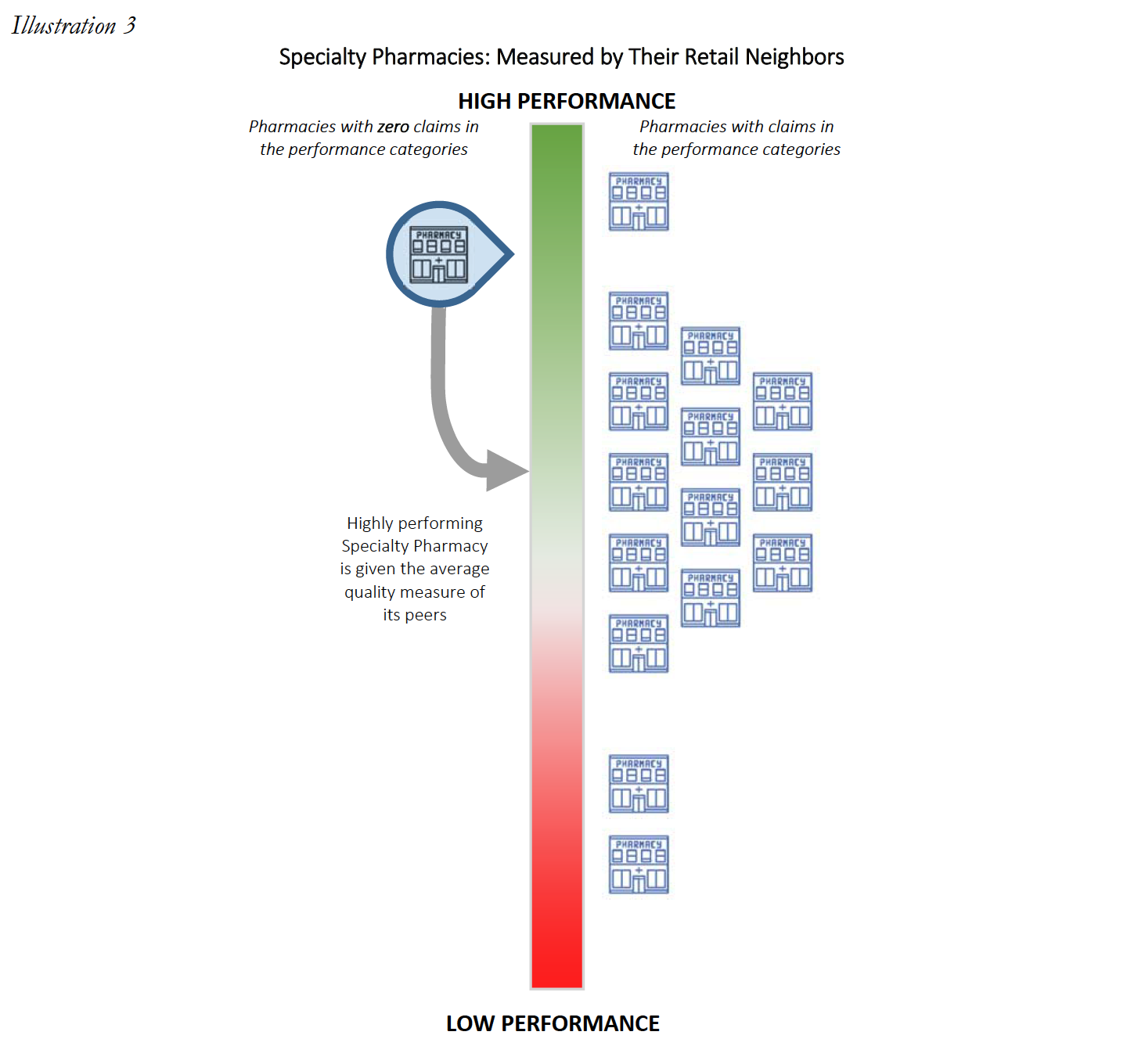

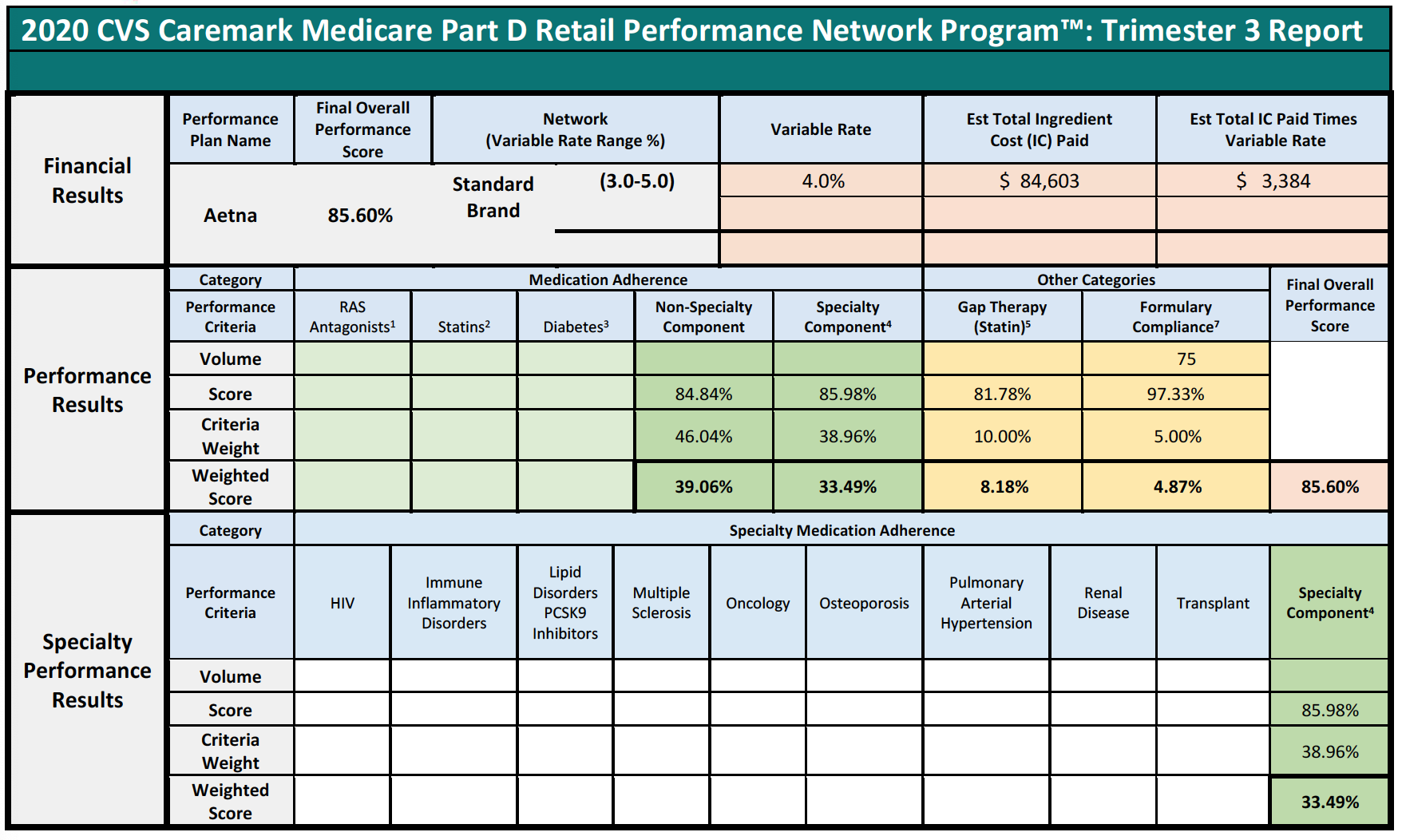

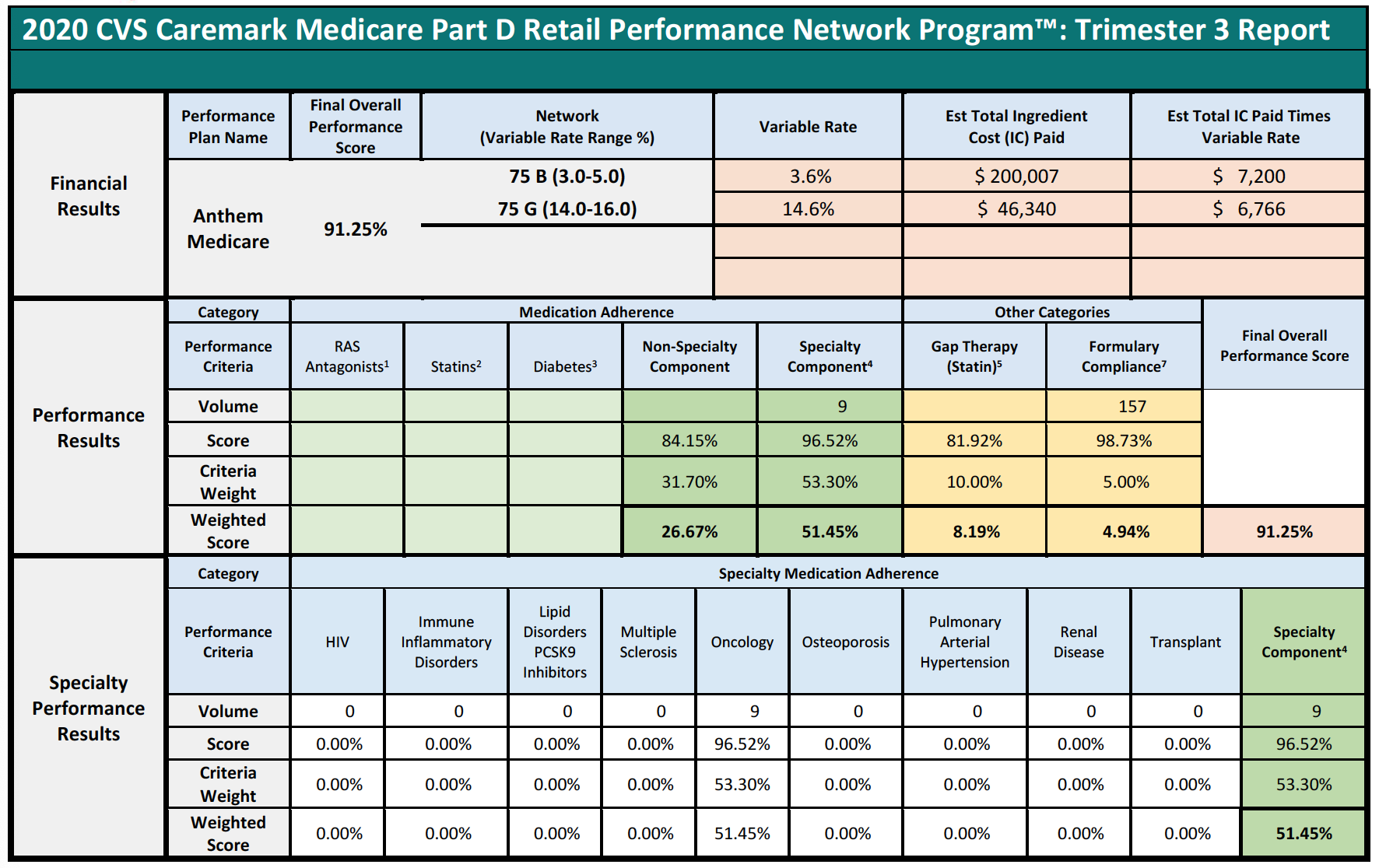

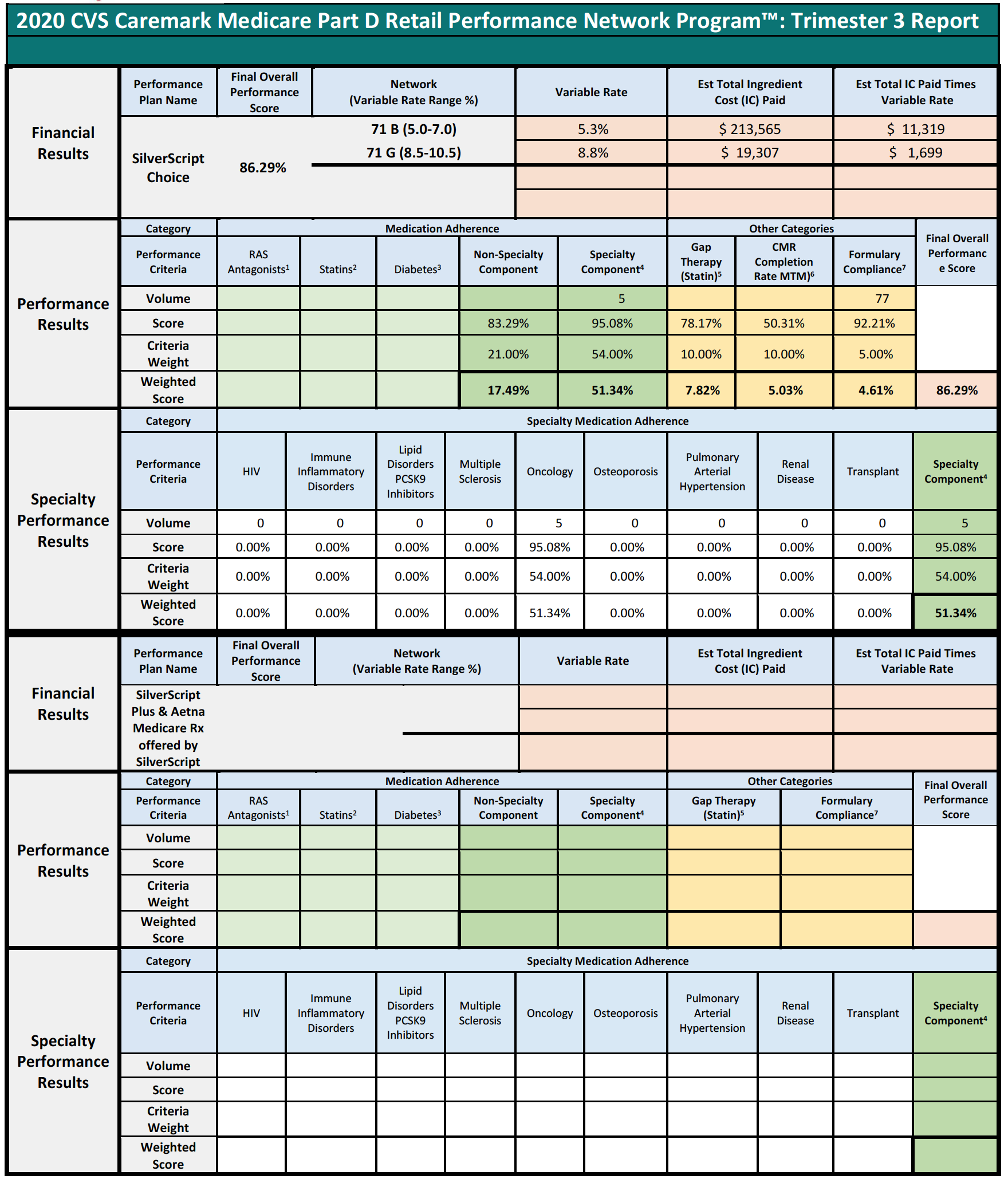

PBMs have recently begun to tie DIR Fees to a pharmacy’s performance in a number of “quality metric” categories established by that PBM. The categories include a variety of different areas of performance, including, but not limited to diabetes adherence, statin adherence, and formulary compliance. Critically, the “quality metrics” utilized by many PBMs to assess a pharmacy’s performance are retail pharmacy-centric, meaning that they focus on retail medications and therapies for commonplace disease states. As such, the criteria reviewed by PBMs are limited in their applicability to pharmacies that dispense retail medications and, as a result, are wholly inapplicable to the business model of Specialty Pharmacies. Rather than simply refrain from assessing DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacies in light of the inapplicability of the “quality metrics,” PBMs have opted to assign the average score of network pharmacies in each “quality metric” category to Specialty Pharmacies and calculate the DIR Fee accordingly. Said another way, PBMs are imposing crippling DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacies based on the average performance of other network retail pharmacies, which have a much different drug mix, and patient and diseasemanagement focus. The effects of these actions have been monumental.

In light of the complex and serious conditions treated, the products dispensed by Specialty Pharmacies are often more expensive than typical retail medications. The medications, however, are not only expensive on the sale-side, but are also incredibly expensive on the acquisition-side. Indeed, mark-ups between what Specialty Pharmacies acquire medications for versus the benchmark prices at which they are reimbursed by PBMs often range between less than 1% to 6%. Thus, Specialty Pharmacies generally dispense medications with only a 2% to 5% gross margin, with no additional reimbursement received for the comprehensive patient care services critical to ensuring optimal patient clinical outcomes. DIR Fees, however, can range from 3% to greater than 5%, and can thus wholly eradicate any profits to be made by Specialty Pharmacies, and in many instances actually result in Specialty Pharmacies losing money when dispensing their medications. What’s worse, Specialty Pharmacies are, in many instances, hamstrung from improving their overall performance score because the “quality metrics” utilized by PBMs are inapplicable because Specialty Pharmacies may only have a small handful, or no, patients to be measured by the quality metrics. Therefore, they are given the network “average” score causing their perceived quality to be lowered and their DIR Fees to increase. The Specialty Pharmacies have no ability to influence quality metrics scores when they do not have patients in the scored categories.

These performance-based DIR Fees threaten not just the ability of Specialty Pharmacies to continue to provide the required patient care support services to Medicare Part D plan participants, but directly harm patients and the Medicare program as a whole by reducing competition and beneficiary access. As confirmed in recent CMS reports, DIR Fees have the effect of shifting financial liability from PBMs and Part D Plan Sponsors to beneficiaries, and ultimately the Medicare program, through higher point-of-sale prices, despite the fact that the PBM claws back a portion of the negotiated price from the pharmacy. In addition, by rendering Specialty Pharmacy’s wholly underwater and forcing them to lose money on every single Medicare claim, PBMs and Part D Plan Sponsors will make it untenable for Specialty Pharmacies to continue to offer the necessary support services for Medicare Part D plan participants, leaving the sickest patients with few alternatives for their live-saving medications and management of their condition.

As a result of the impact DIR Fees have had on Specialty Pharmacies throughout the country, members of the media and the pharmacy industry have begun scrutinizing PBMs and the practice of assessing DIR Fees. The United States Senate and House of Representatives have each introduced proposed legislation aimed at addressing DIR Fees and CMS has issued reports commenting on the impact DIR Fees have on the Medicare Part D program and Medicare beneficiaries. However, more can and must be done to curtail the assessment of DIR Fees, or else patients and taxpayers alike will continue to suffer.

Introduction

Perhaps more so than any other segment of the U.S. healthcare system, the coverage, management, and reimbursement of prescription drugs in this country is incredibly complex. The management and administration of pharmacy claims is controlled by a handful of companies known as pharmacy benefit managers, or “PBMs.” Essentially middleman, these companies contract with “Plan Sponsors” such as health insurance companies, large employers, union groups and government programs (such as TRICARE) to administer the “pharmacy benefits” for these plan sponsors– with the medical benefits typically being managed separately. In turn, PBMs contract with a network of retail and specialty pharmacies, and negotiate with and process pharmacy claims submitted by these providers. PBMs also negotiate directly with manufacturers for rebates or other pricing concessions, in exchange for placing a particular manufacturer’s drug on the PBM’s formulary. These PBMs (such as Express Scripts, Humana, CVS Caremark, and OptumRx) are often massive companies, that strangely most Americans have never even heard of.

Among the “Plan Sponsors” that PBMs contract with are Medicare part D Plan Sponsors. Medicare Part D Plan Sponsors may be insurance companies, managed care organizations, or other entities that create and manage a Prescription Drug Plan made available under the Medicare Part D Program. As noted below, many Part D Plan Sponsors are owned or affiliated with the PBMs with whom they contract.

Medicare Part D was created following the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003 (“MMA”), and established for the first time comprehensive outpatient prescription drug coverage for Medicare Part D beneficiaries. Under Medicare Part D, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (“CMS”) contracts with Part D Plan Sponsors to administer the Medicare drug benefit. Part D Plan Sponsors in turn contract with PBMs (many of whom may own, are owned by, or are affiliated with Part D Plan Sponsors) to administer the plans. PBMs in turn contract with pharmacies to provide services to plan beneficiaries. In addition to contracting with independently owned pharmacies, many PBMs also own their own retail, mail order, or specialty pharmacies. These wholly-owned pharmacies service the public, but benefit from PBM underwriting to directly compete with independently owned pharmacies. DIR Fees ultimately have the effect of steering business to the PBM wholly-owned specialty pharmacies allowing the PBM to capture DIR Fees at the plan level as increased profits.

Among the pharmacy providers with whom PBMs contract include retail pharmacies and specialty pharmacies. Retail pharmacies are generally defined as duly-licensed community pharmacies that primarily fill and sell a wide array of brand and generic prescription medications via retail storefront. Retail pharmacies – which may be chains or independents – provide general prescription drug services to general populations customers (walk-in or serviced through local delivery), and dispense commonly prescribed drugs and medication therapies, based on the habits of local prescribers and/or local plan formularies.

Meanwhile, Specialty Pharmacies are state-licensed pharmacies that predominantly provide medications for people with serious health conditions requiring complex therapies. These include conditions such as cancer, hepatitis C, rheumatoid arthritis, HIV/AIDS, multiple sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, organ transplantation, human growth hormone deficiencies, and hemophilia and other bleeding disorders. The specialty medications used to treat these conditions are often more complex than most prescription medications, and may have special administration requirements (such as injectable medications or infused medications), in addition to special storage and delivery requirements. The complexity of these medications may be due to the drugs themselves, the way they are administered, the management of their side effect profiles, or issues surrounding the access to those medications.

In addition to being state-licensed and regulated, Specialty Pharmacies are also often accredited by one or more independent third parties, such as URAC, the Accreditation Commission for Health Care (“ACHC”), the Center for Pharmacy Practice Accreditation (“CPPA”) or the Joint Commission, and often employ Certified Specialty Pharmacists to deliver care. Specialty Pharmacies also provide a variety of clinical and support services that retail pharmacies are not equipped nor prepared to provide. This includes providing patient care services required for certain complex specialty medications (i.e., nursing support), providing patient training on how to administer specialty medications (i.e., instructions on how to self-administer injectable medications), assisting with patient support services for patients who are facing reimbursement challenges for these lifesaving but often costly medications, ensuring special handling of certain specialty medications with unique requirements, and engaging in ongoing patient monitoring based on medication and therapy requirements.

The heightened services and customer care provided by Specialty Pharmacies has undoubtedly had an extraordinary impact on patients and physicians alike. For instance, one testimonial recently received by a Specialty Pharmacy reads:

I want to put a very special word in for [a Specialty Pharmacist] and how kind and helpful she is and how much easier she made what could’ve been a confusing first (and second experience) when ordering through a specialty pharmacy, which I had never done before. She was able to explain everything about the drug to me (something I had never taken before and was quite nervous about starting due to it being a strong narcotic) and answer all my questions and by the time we were finished I was quite comfortable with the idea of the new medication I would soon be starting.

A medical provider recently submitted a testimonial with similar sentiments:

Always mindful of side effects, [Specialty Pharmacy A] always keeps me informed of patient interactions, or when a patient may need something that they have not reported directly to me…the patient is educated in office and over the phone by [the Specialty Pharmacy’s] pharmacists. The patients hearing the information twice helps adherence…

Simply put, the services provided by Specialty Pharmacies have an overwhelming impact on patient adherence. It has been documented that only 50% of patients with chronic conditions take their medication as directed. There are a multitude of reasons why Medicare patients suffer from nonadherence, including forgetfulness, a desire to avoid adverse medication side-affects, and high cost. Estimates indicate that nonadherence to prescription drug regimens cost $105 billion in annual avoidable health care costs.

However, the approaches utilized by Specialty Pharmacies when assisting their patients have demonstrably decreased the nonadherence rates for patients taking specialty medications One study revealed that patients who exclusively used Specialty Pharmacies had a 60% higher adherence rate when compared with patients using retail pharmacies, while another study found that Specialty Pharmacies, on average, had a 8.6% higher adherence rate when compared to retail pharmacies. Specifically, studies show that adherence rates in specific specialty therapies are far greater than the average adherence rate for retail medications, with multiple sclerosis at 95.33%, rheumatoid arthritis at 94.65%, HIV at 97%, and Crohn’s disease at 95.68%.6 This is due in no small part to the expert services that Specialty Pharmacies provide, with no additional reimbursement, which drive adherence and persistency, proper management of medication dosing and side effects, and ensure appropriate medication use, while supporting the needs of some of our nation’s highest risk patients.

The businesses of specialty pharmacy and retail pharmacy operate very differently, both in terms of operational margins, ancillary services provided, and infrastructure required to support the complex medications and disease states associated with the specialty pharmacy business model.

Why Don’t Retail Pharmacies Dispense Specialty Medications?

Overall, retail pharmacies do not dispense medications that are used to treat patients afflicted by conditions requiring these complex specialty drugs and biologics because these conditions are not widely prevalent in the general population serviced by retail pharmacies. Additionally, the specialty medications that are dispensed by Specialty Pharmacies carry high overhead cost, and require additional technical capabilities. Costs incurred by Specialty Pharmacies include extremely expensive inventory, additional infrastructure (i.e., 24‐hour telephone access to pharmacists and temperature controlled storage/shipping), and additional staffing to assist with administration of specialty medication (i.e., skilled nursing network and patient training professionals). Specialty Pharmacies must also closely coordinate with physician offices to monitor patient conditions/adverse effects, aid in completing prior authorization requirements imposed by insurance companies, and ensure adherence to complete treatment regiments. Retail pharmacies cannot justify making the related investment if specialty medications that require these costs make up only a small percent of their normal customer base. Instead, Specialty Pharmacies are better equipped to be implement the structural requirements to dispense specialty medications and engage in the required close coordination with the physicians’ offices to function within the healthcare continuum for these complex disease states.

Recently, within the Medicare Part D Program, many PBMs and Part Plan Sponsors have begun to introduce and expand “fees” being charged to pharmacies under the guise of “network rebates,” “performance variable rates,” or “direct and indirect remuneration” – or “DIR” – Fees. As noted below, many of these DIR Fees have had a grossly disproportionate impact on Specialty Pharmacies with percentage-based fees being particularly damaging.

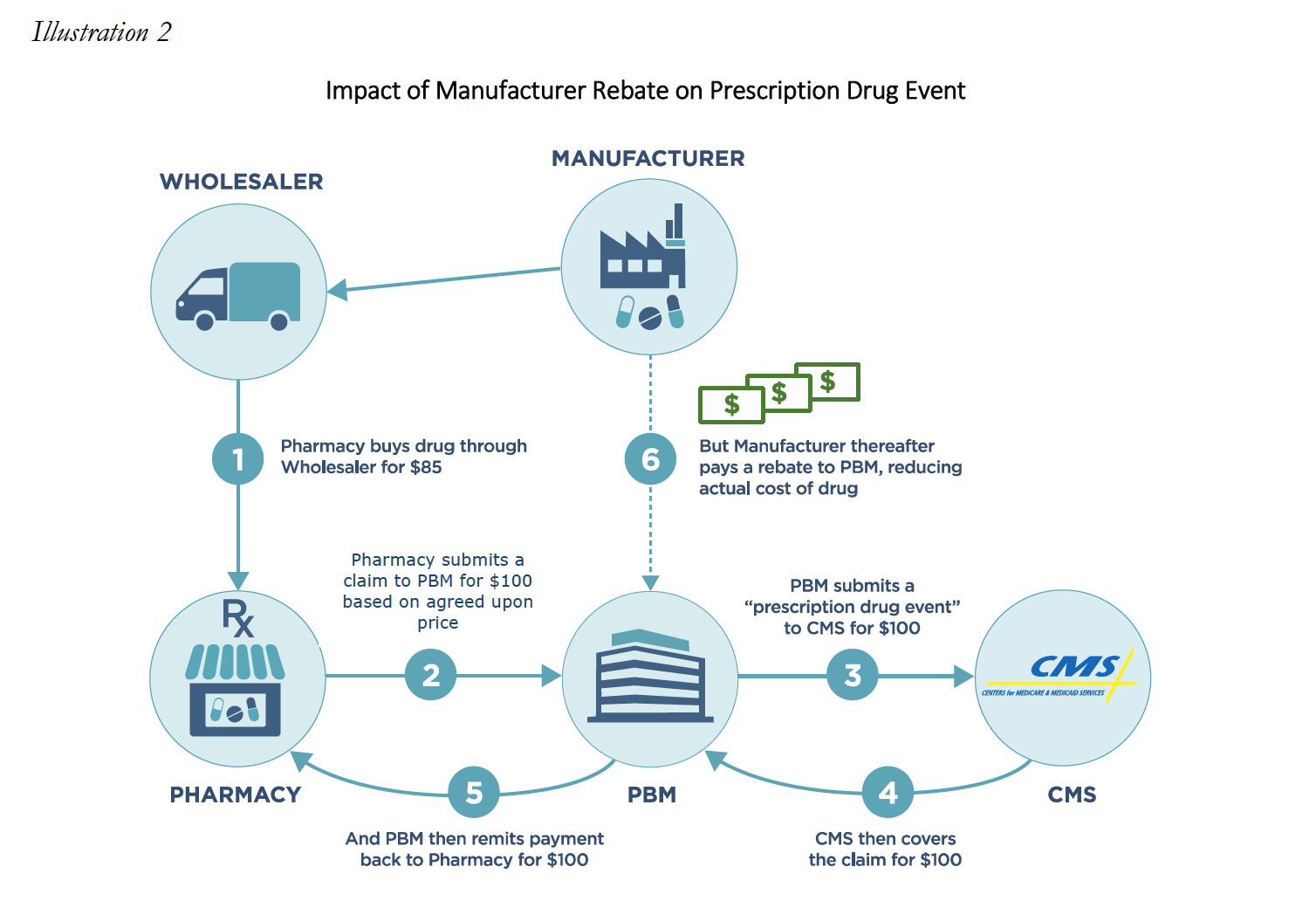

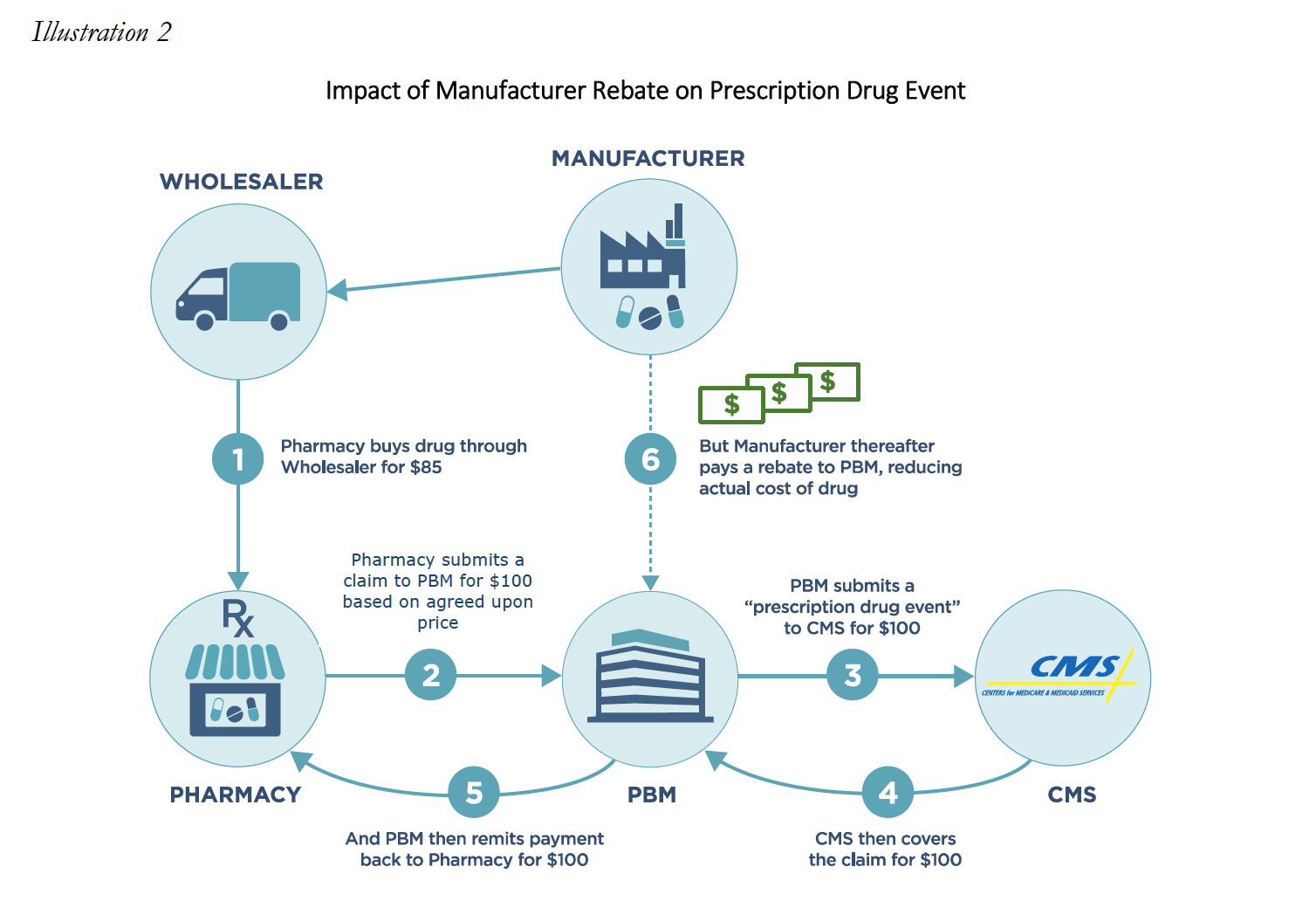

As part of the Part D program, plan sponsors must report actual costs of all drugs covered under Part D, inclusive of all “direct” and “indirect” remuneration received from third-parties. Historically, the bulk of DIR received by plan sponsors and their agents was made up of manufacturer rebates that could not reasonably be calculated at the point-of-sale for the Part D covered medication. CMS wanted to ensure that it knew of and could share in part of the savings realized from manufacturer rebates. CMS also contemplated scenarios where providers, such as pharmacies, might actually be entitled to additional compensation based on performance. Overall, the original purpose of the DIR calculation and report was intended to provide the true cost of medication dispensed to Medicare beneficiaries, as evidenced below in the simplified illustration.

However, many PBMs have taken this framework and used it to justify the assessment of after-the-fact “DIR Fees” against network providers, including Specialty Pharmacies. These DIR fees charged to pharmacies are distinct from the original DIR as contemplated under the MMA. Instead of incentivizing increased performance, many PBMs have manipulated DIR to instead extract additional monies from pharmacies, including on high cost specialty medications. Such DIR Fees can take the form of either a flat fee per prescription based fee, or may be a percentage-based DIR Fee that is calculated using the ingredient cost of the dispensed medication.

Both percentage-based and flat rate DIR Fees pose serious problems and questions for pharmacies, who are assessed these murky fees either at the time of reimbursement or sometimes months after the fact, but the percentage-based fees have an increased propensity for serious consequences as these fees can be 1,000% to 10,000% higher than flat rate DIR Fees. Many DIR Fee constructs are nothing more than a “tax” on pharmacies, or a fee paid by providers for the privilege of participating in the PBM’s network, regardless of whether they are cast as flat fee or percentage-based DIR.

However, under the guise of “performance-based” fees, some PBMs have levied an extraordinary cost on Specialty Pharmacies in particular by calculating DIR Fees as a percentage of gross drug reimbursement per claim. This type of percentage-based fee is a particularly egregious example of PBM-imposed DIR Fee constructs, and imposes an exceptionally high and burdensome cost on Specialty Pharmacies, as the predominance of their dispensing volume is expensive medication. The disparate impact on specialty pharmacies becomes especially clear when fees extracted from specialty pharmacies, sometimes months after medication is purchased and dispensed to patients, result in the pharmacy being reimbursed below the acquisition cost of the medication. This extraordinary result stems from the fact that Specialty Pharmacies operate in a market where the expected profit margin is a small percentage of the total cost of the medication. Further, the calculation of the DIR Fee relates primarily to qualitative measures that are not applicable to specialty pharmacies.

In this White Paper we will explore the impact DIR Fees have on one subset of healthcare providers, Specialty Pharmacies. We will explain how performance-based DIR Fees, particularly those calculated as a percentage of drug cost, have a disproportionate impact on Specialty Pharmacies and the expensive medications they dispense. This disproportionate impact is compounded, as the “quality metric” categories utilized in calculating DIR Fees review categories of information that are distinctly irrelevant to the drugs dispensed and services provided by Specialty Pharmacies. Specialty Pharmacies are further disproportionately impacted by such unreasonable and irrelevant DIR Fees because of the high concentration of specialty medications they dispense, compared to their retail counterparts (for whom DIR Fees were primarily designed). This White Paper will also explore the impact that such DIR Fees – when applied in the Specialty Pharmacy context – have on Medicare Part D beneficiaries and the Program alike. In particular, it will examine the shifting of financial liability from PBMs (including those owned or aligned with Part D Plan Sponsors) to taxpayers and beneficiaries (many of whom are among the most vulnerable population). Finally, we examine the current state of affairs of DIR Fees, as it relates to Specialty Pharmacies and their patients, and what more can and must be done to curb this abusive and destructive practice.

This White Paper was commissioned by the National Association of Specialty Pharmacy (“NASP”). The findings reflect the independent research and opinions of the authors; Frier Levitt, LLC does not intend to endorse any product or organization. The use of any registered trademarks or logos is purely for reference and educational purposes only. This report and any conclusions or inferences drawn therefrom represent the opinions of Frier Levitt, LLC. If this report is reproduced, we request that it be reproduce in its entirety, as pieces taken out of context can be misleading.

Performance-Based DIR Fees

DIR Fees can encompass a number of charges to Specialty Pharmacies, including “pay-toplay” fees for preferred pharmacy networks, network access fees, and administrative fees. However, the type of DIR Fees that have created recent shockwaves throughout the specialty pharmacy industry are the “performance-based” DIR Fees. Indeed, performance-based DIR Fees have effectively clawed back millions of dollars from Specialty Pharmacies nationwide, and have detrimentally impacted Medicare Part D and its beneficiaries, and threaten the future of patient care access and choice.

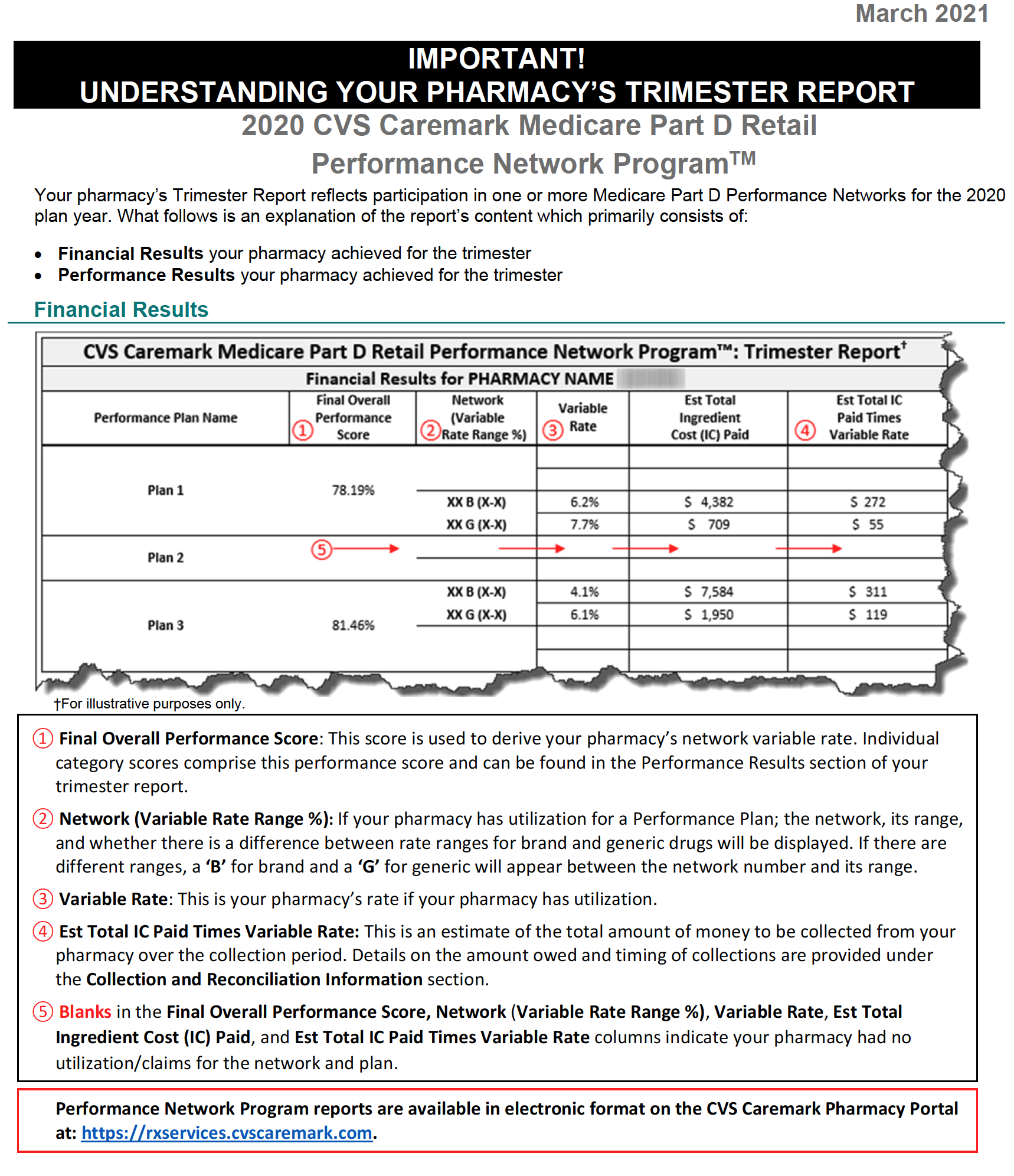

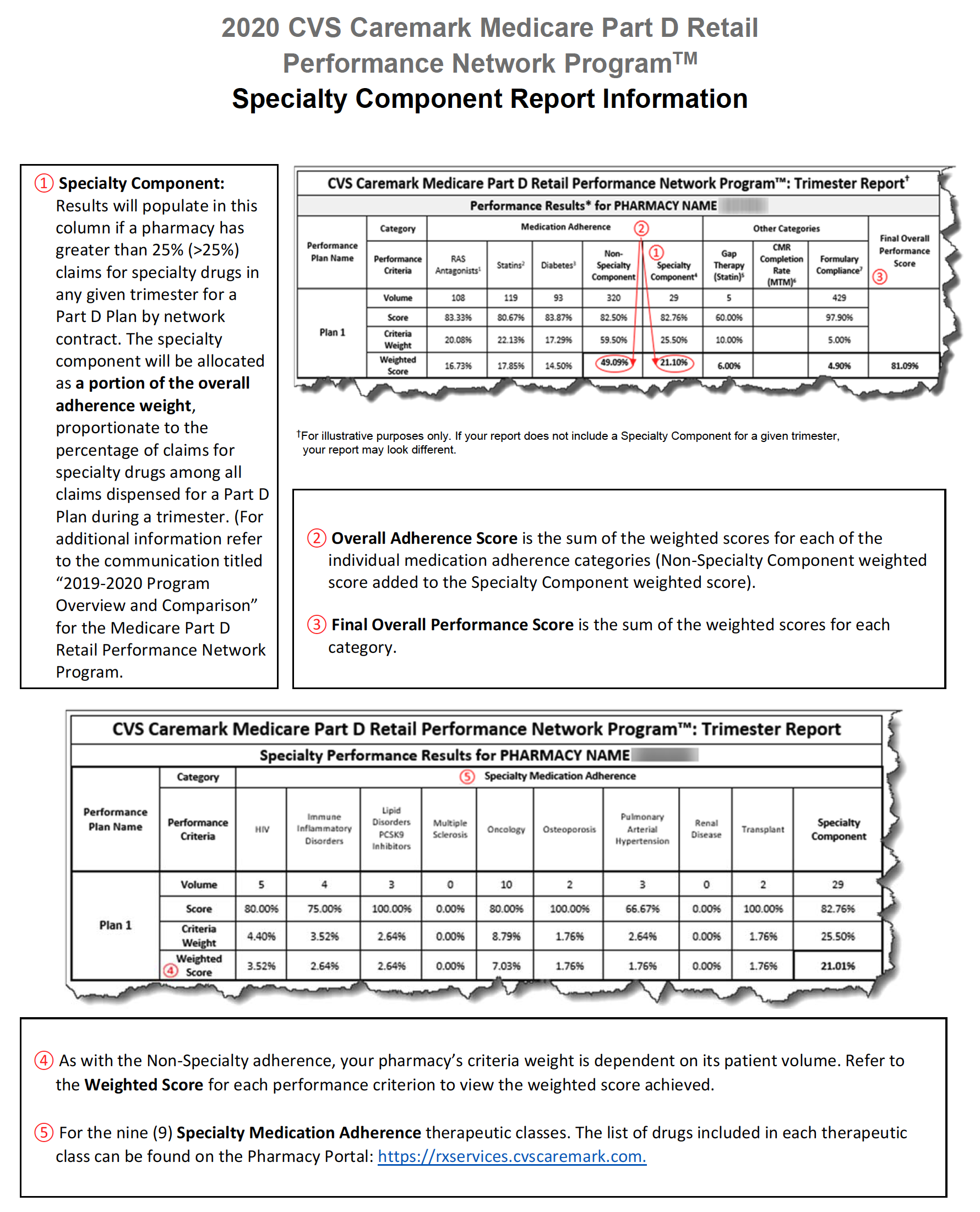

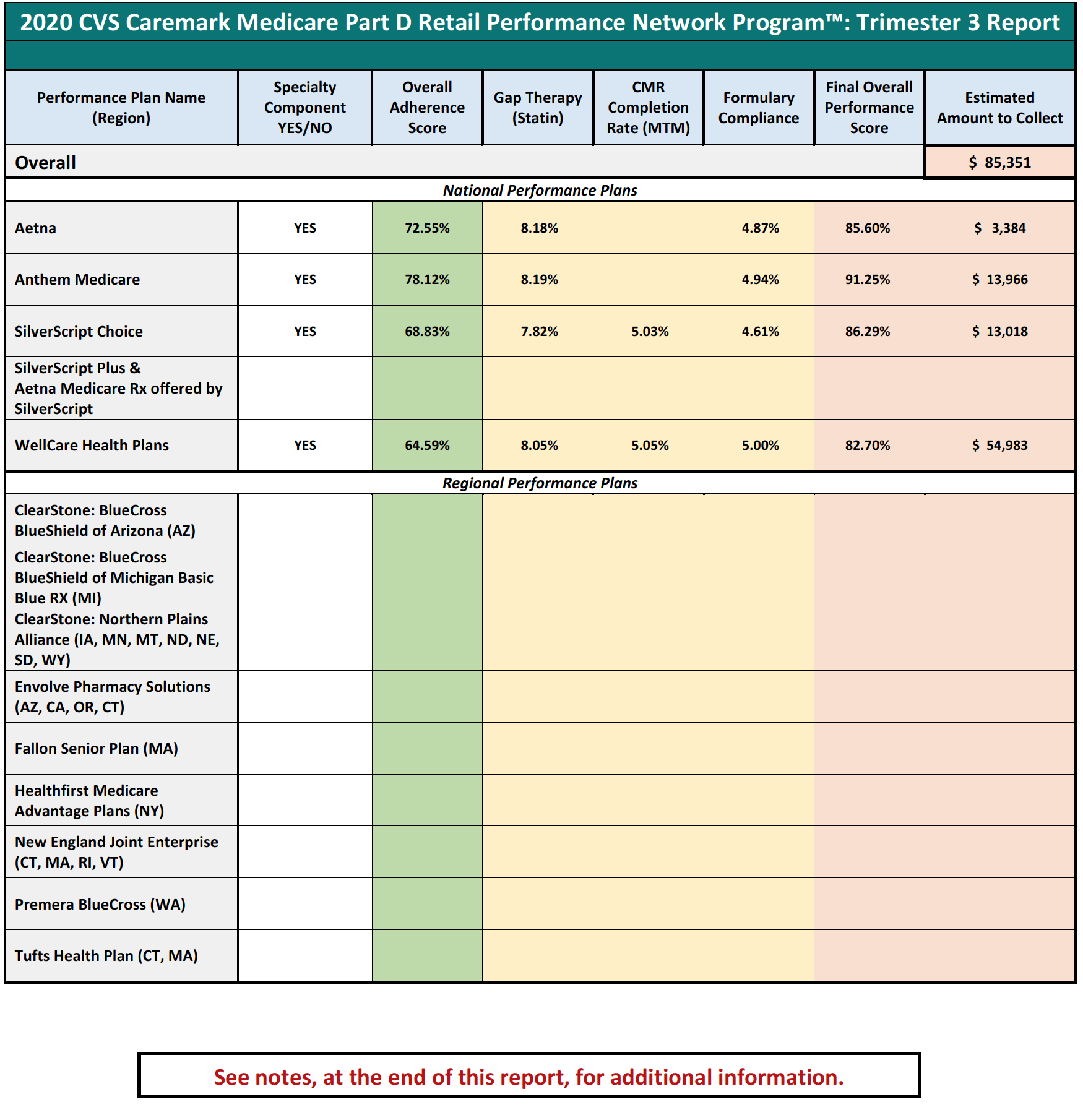

Performance-based DIR Fees are often based on a pharmacy’s performance in a number of “quality metric” categories, established by the PBM. The categories can include a variety of different areas of performance, including ACE/ARB adherence, statin adherence, diabetes adherence, Comprehensive Medication Review (“CMR”) completion rate, and formulary compliance. Under performance-based DIR Fee programs, the amount of DIR Fees assessed against a pharmacy depends on the pharmacy’s performance in these categories, with lower performing pharmacies being assessed a higher percentage-based DIR Fee and better performing pharmacies being assessed lower DIR Fees. Importantly, the quality metric categories are weighted, which means that certain quality metric categories count more toward the overall performance of the pharmacy than others. Some categories can weigh as much as 25%, whereas other categories can weigh as little as 5%. Regardless, the quality metric categories are virtually inapplicable to Specialty Pharmacies.

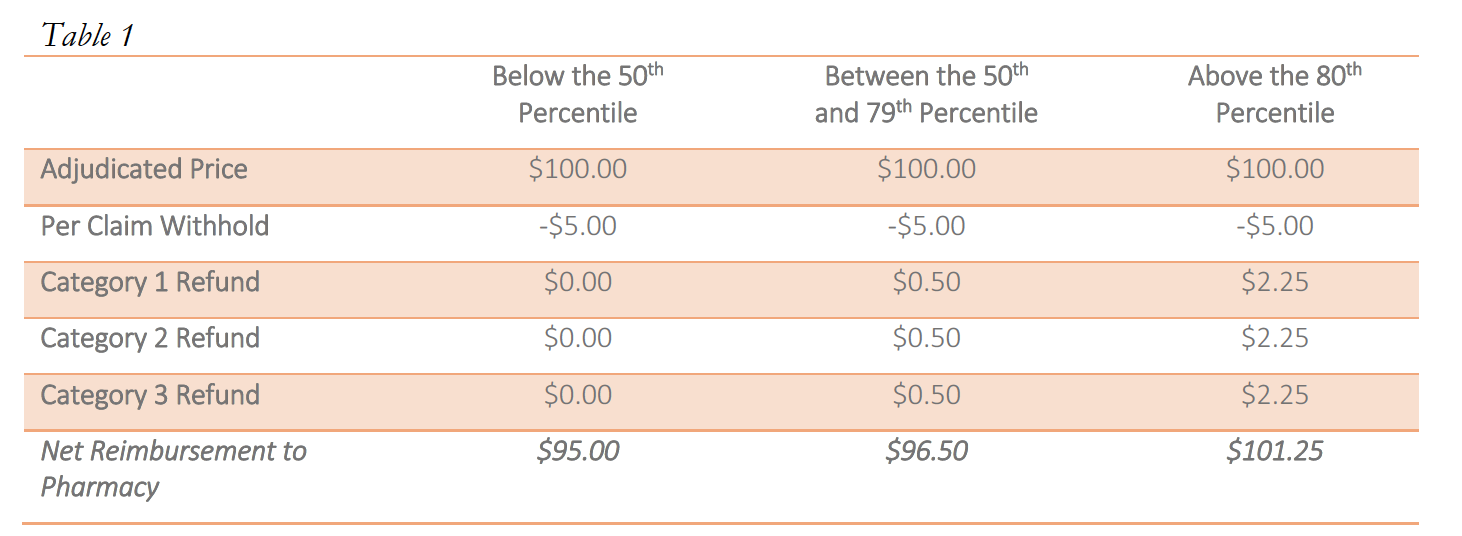

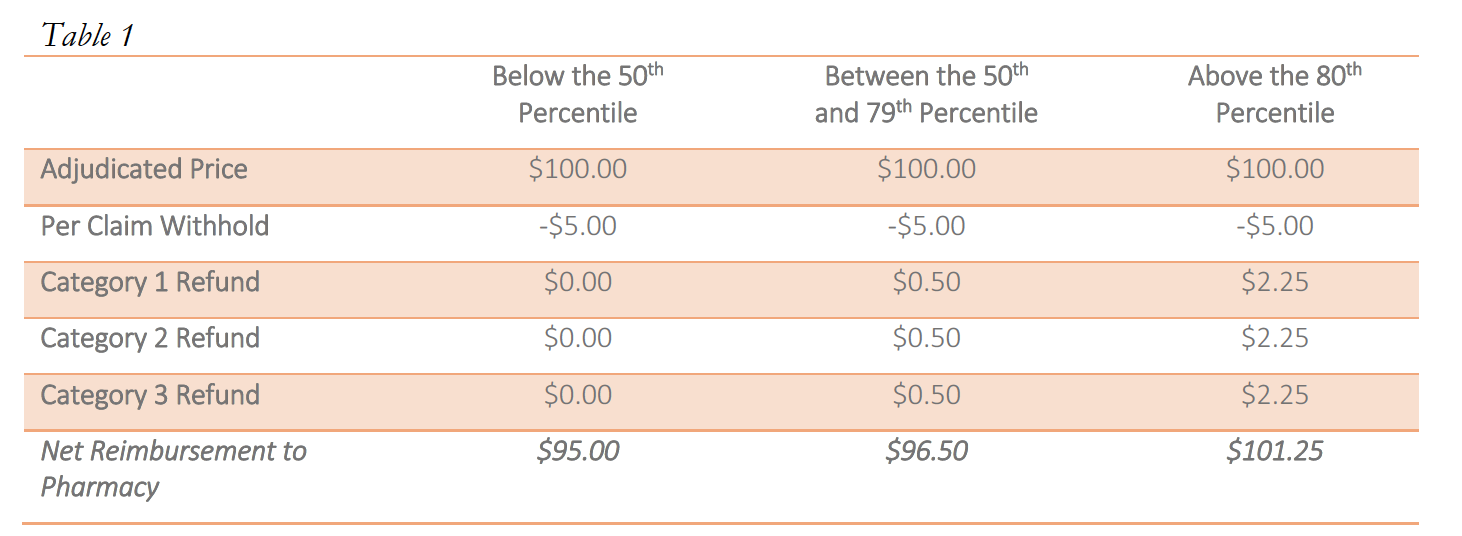

Performance-based DIR Fees can be assessed one of two ways: flat fee or percentage. An example of a flat-fee performance-based DIR Fee would have the PBM withhold $5.00 from each claim submitted by a pharmacy to the PBM. Thereafter, the PBM will review the pharmacy’s performance in three categories. For each category the Specialty Pharmacy scores in at least the 50th percentile but below the 80th percentile, the pharmacy will be refunded $0.50. For each category the pharmacy scores above the 80th percentile, $2.25 will be refunded. As such, the pharmacy stands to potentially pay a $5.00 DIR Fee on each claim if its performance score is below the 50th percentile in all three categories, but can potentially receive a DIR “bonus” of $1.25 if its performance score is above the 80th percentile in all three categories. This is illustrated in Table 1 (below).

Notwithstanding the proposed availability of a “bonus,” there is limited evidence that bonuses are paid out, particularly in the specialty pharmacy context. As noted above, these flat rate DIR Fees can pose serious problems for retail and specialty pharmacies alike, particularly where there is little actual ability for the provider to influence the performance scores.

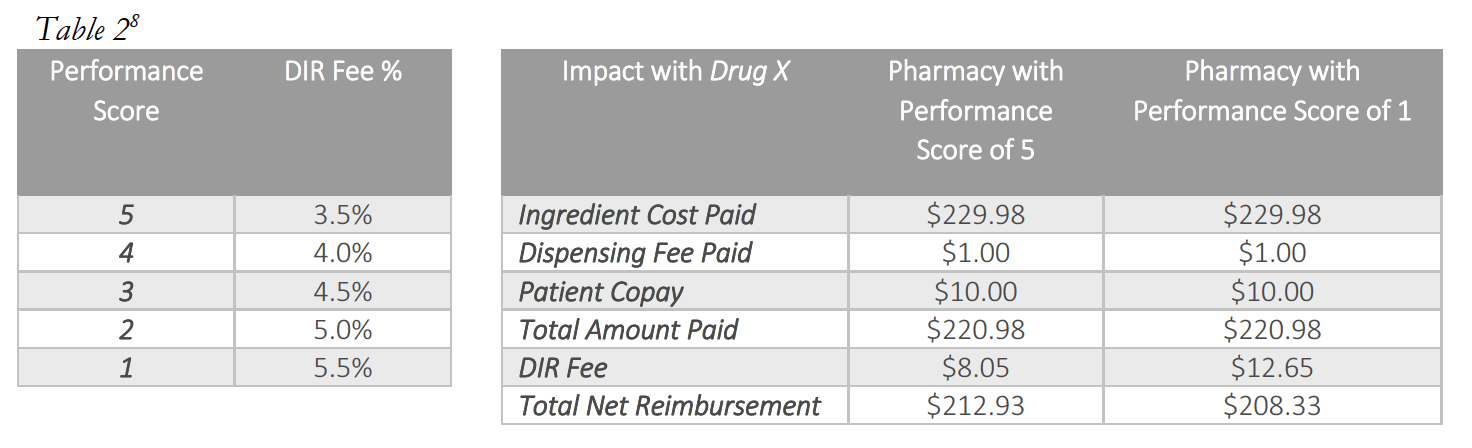

However, performance-based DIR Fees may also be percentage-based. If such DIR Fees are percentage-based, a percent of the total claim submitted by the pharmacy to the PBM will be recouped by the PBM as a DIR Fee. The percentage clawed back by the PBM is calculated using the pharmacy’s performance in quality metric categories. While in prior years, non-performance-based DIR Fees were retracted at the time of initial payment by the PBM (typically within the same 14-day claims cycle during which pharmacy claims were normally paid in the first case), more recent performance-based DIR Fees are not calculated or assessed until months later, leaving the pharmacy totally clueless as to the true “net amount” they would ultimately be paid for the claim. Similar to the flat-fee model explained above, pharmacies are assessed a lower percentage DIR Fee if they perform “better” in the quality metric categories. However, under certain models, a certain minimum percentage DIR Fee will be assessed by the PBM, regardless of how well the pharmacy performs in the quality metrics. These percentage-based DIR Fees usually range from 0% to 9%, with many falling in the range of 3% to greater than 5% of the total claim submitted. This is illustrated in Table 2 (below).

Most critically, as it applies to Specialty Pharmacies, each pharmacy will generally be assessed DIR Fees based on these fixed “quality metric” categories, irrespective of whether the pharmacies have any claims subject to the reporting and measurement criteria. Said another way, each pharmacy – including Specialty Pharmacies – will be judged by select PBMs using the same set of “quality metric” categories, even if the Specialty Pharmacy’s business model renders the “quality metric” categories wholly inapplicable. What’s worse, in a circumstance where a Specialty Pharmacy does not fill claims that fall within a particular “quality metric” category, the Specialty Pharmacy will receive the Part D plan’s representative performance score for that “quality metric” category for that particular review period. Thus, a Specialty Pharmacy’s performance score in a particular “quality metric” category is often dictated by average performance scores of the other retail pharmacies within the network on products that the Specialty Pharmacy generally does not dispense at all. Ultimately, and as detailed below, based on the imposition of the average performance scores of other retail pharmacies within the network, the DIR Fees imposed on Specialty Pharmacies in these cases are largely unrelated to the Specialty Pharmacy’s performance, medications dispensed or services provided.

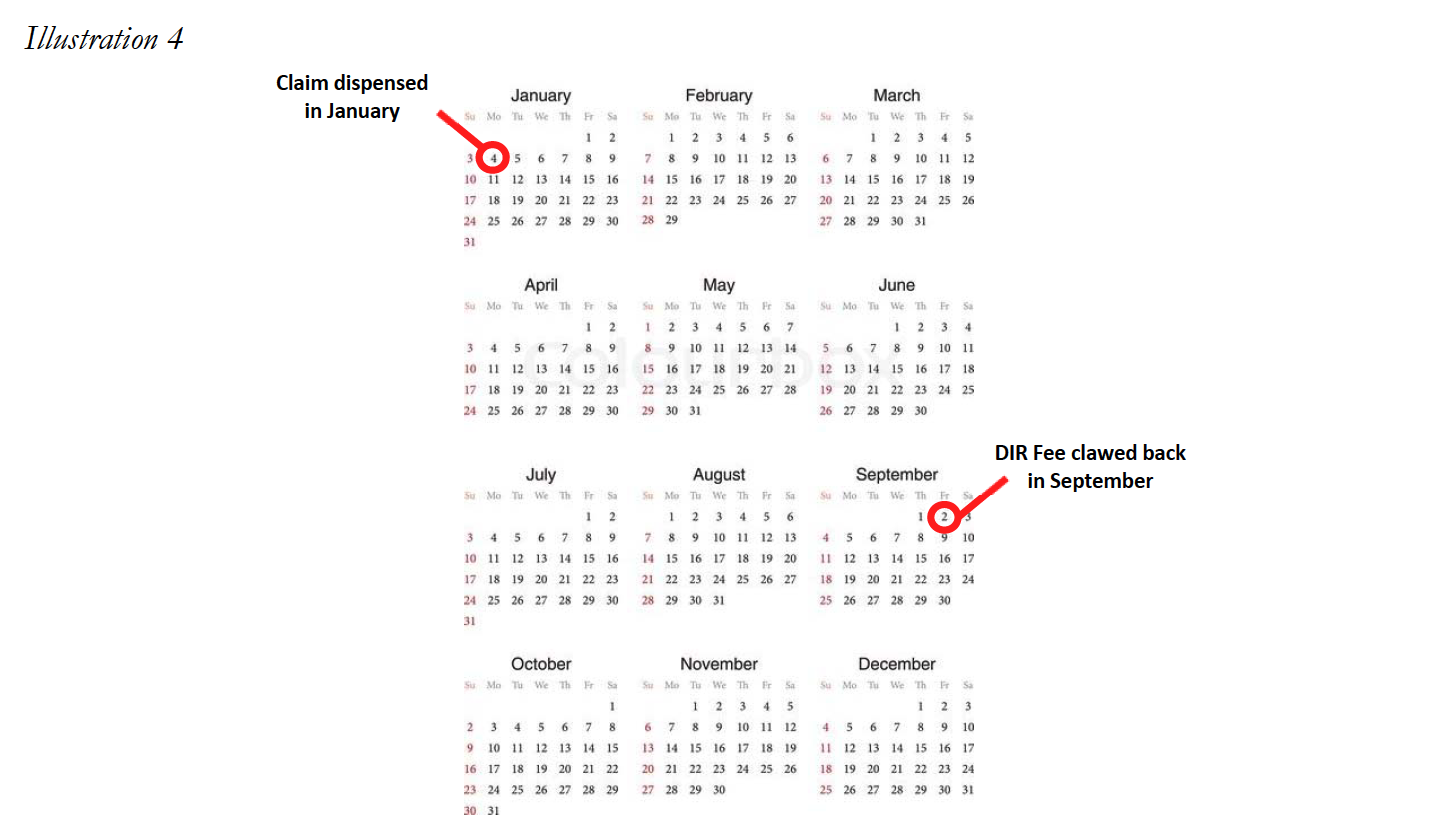

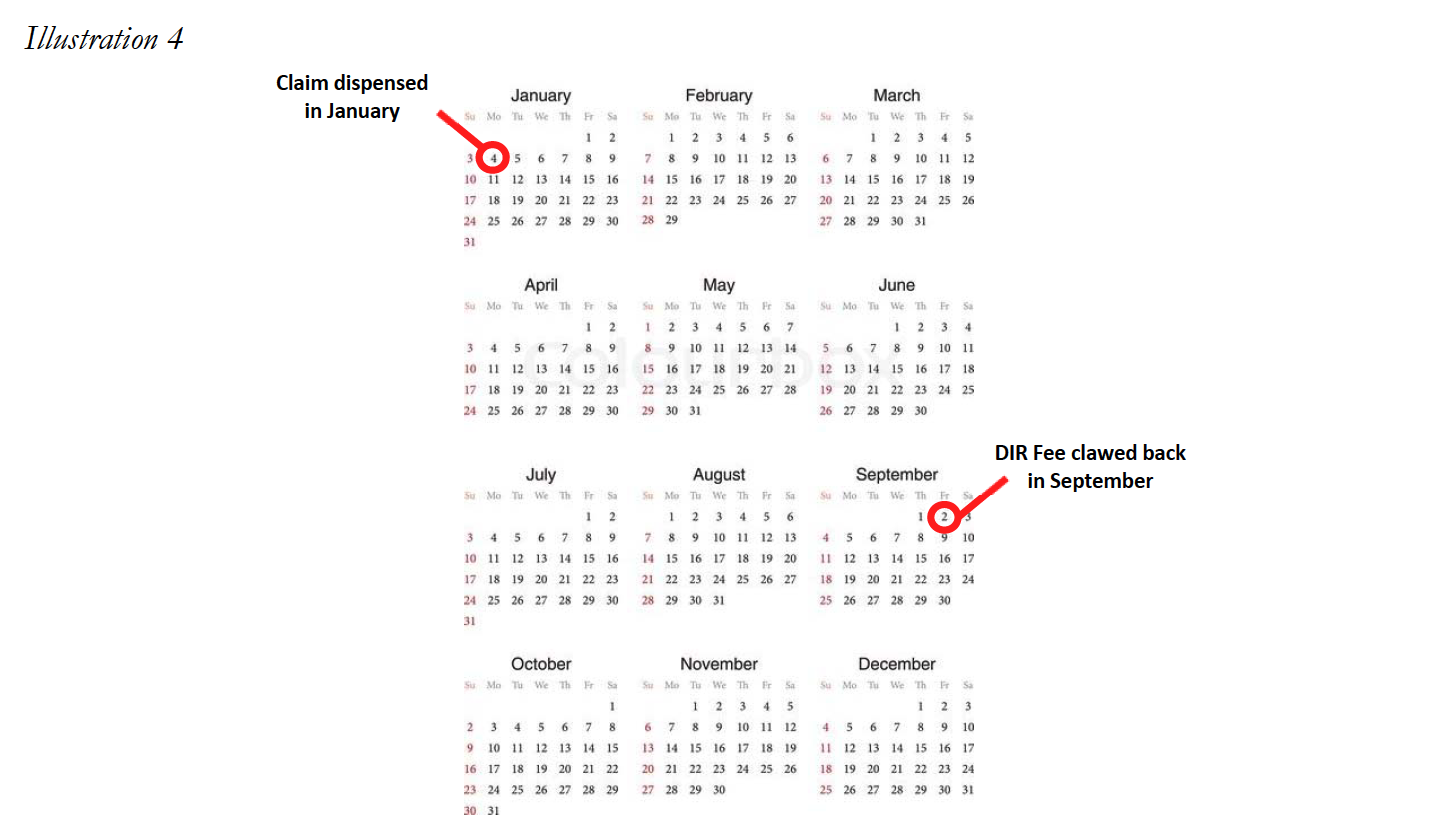

The PBMs’ timing of assessing DIR Fees is also a huge problem. Aside from the tremendous costs charged by PBMs to Specialty Pharmacies in connection with DIR Fees, the method PBMs use to calculate DIR Fees serve to add “insult to injury.” DIR Fees are calculated retrospectively, which, in effect, means they are assessed against Specialty Pharmacies many months after the drug has been dispensed to the patient and the Specialty Pharmacy has been reimbursed. For example, a prescription dispensed in January may not have a DIR Fee assess until as late as September.

This creates immense uncertainty at the time the medication is dispensed as to how much the Specialty Pharmacy will ultimately be reimbursed for the product (not to mention for CMS to know exactly how much is actually being paid for the drug). The inability to understand true reimbursement for medications dispensed makes it nearly impossible for the Specialty Pharmacy to properly account for projected revenues and cash flows, particularly where it is expected to provide substantial ancillary services to patients (i.e., training, adherence monitoring, and collaboration with other healthcare providers) in order to ensure a high level of patient care on complex disease states. Overall, this lack of visibility jeopardizes the ability of Specialty Pharmacies to continue to provide the necessary comprehensive patient support services to ensure maximal therapeutic outcomes to Medicare Part D plan participants, thereby greatly diminishing the level of care and treatment of some of our country’s sickest and most vulnerable patients. Unfortunately, as set forth in greater detail below, it appears that this murky construct may be by design.

The Negative Impact of DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacies

Specialty Pharmacies operate as a niche provider in the healthcare space and serve a critical role in the country’s healthcare continuum. These pharmacies provide medication to the sickest and most vulnerable members of society. The medications utilized by this population are almost all extremely complex and typically require special handling both in processing claims (as the dispensing of the medications needs Prior Authorization beyond merely a prescriber’s prescription), as well as provision of the medication to the patient (such as maintenance of medication at a cold temperature from manufacture until patient administration). The complexities related to Specialty Pharmacies highlight the important role of these healthcare providers and explain why the application of DIR Fees to this segment of the healthcare system must be analyzed accurately and practically. Failing to do so will result in a plethora of unintended consequences that will be detrimental to the healthcare system as a whole, and to Medicare in particular.

Unfortunately, PBM-imposed performance-based DIR Fees have had a severe and disparate impact on Specialty Pharmacies. Specialty Pharmacies have no ability to influence, control, or drive the quality measurements utilized by PBMs in many of their current DIR Fee programs, yet PBMs nevertheless assess DIR Fees – whether flat-fee or percentage-based – against Specialty Pharmacies for measures they have no ability to control. Moreover, given the unique nature of the specialty pharmacy industry and alternative distribution framework for many specialty medications, the result of these post-hoc DIR Fees has often led to unreasonable, below-acquisition reimbursement rates which severely negatively impact Specialty Pharmacies’ ability to continue to provide the critical support services to Medicare Part D plan participants, seriously jeopardizing the health and welfare of Medicare Part D beneficiaries. Finally, this disproportionate and unreasonable impact on Specialty Pharmacies is exacerbated by the fact that such Specialty Pharmacies have a higher percentage of high-cost specialty medications (which are sometimes limited distribution in nature), given the patient populations they serve.

Far beyond merely reducing profits, DIR Fees force Specialty Pharmacies to often times dispense drugs far below their acquisition costs. This section endeavors to explore the nature and scope of that negative impact on Specialty Pharmacies.

4.1 DIR Fees’ Effect on Specialty Pharmacy Reimbursement

An understanding of how DIR Fees impact reimbursements for Specialty Pharmacies requires first an understanding of the economics of the specialty pharmacy drug distribution channel. The manufacture, sale, and distribution differ markedly for specialty products, as compared to the distribution of traditional brand and generic retail medications.

First, specialty products (whether drugs or biologics) often treat serious, critical, complex, rare, and life-threatening conditions, such as cancer, Hepatitis C, HIV, and Multiple Sclerosis. As such, specialty products are often newer, breakthrough products, with little or no generic alternatives available. Given that they are primarily branded medications, manufacturers have a substantially greater amount of control over the distribution and pricing of these products.

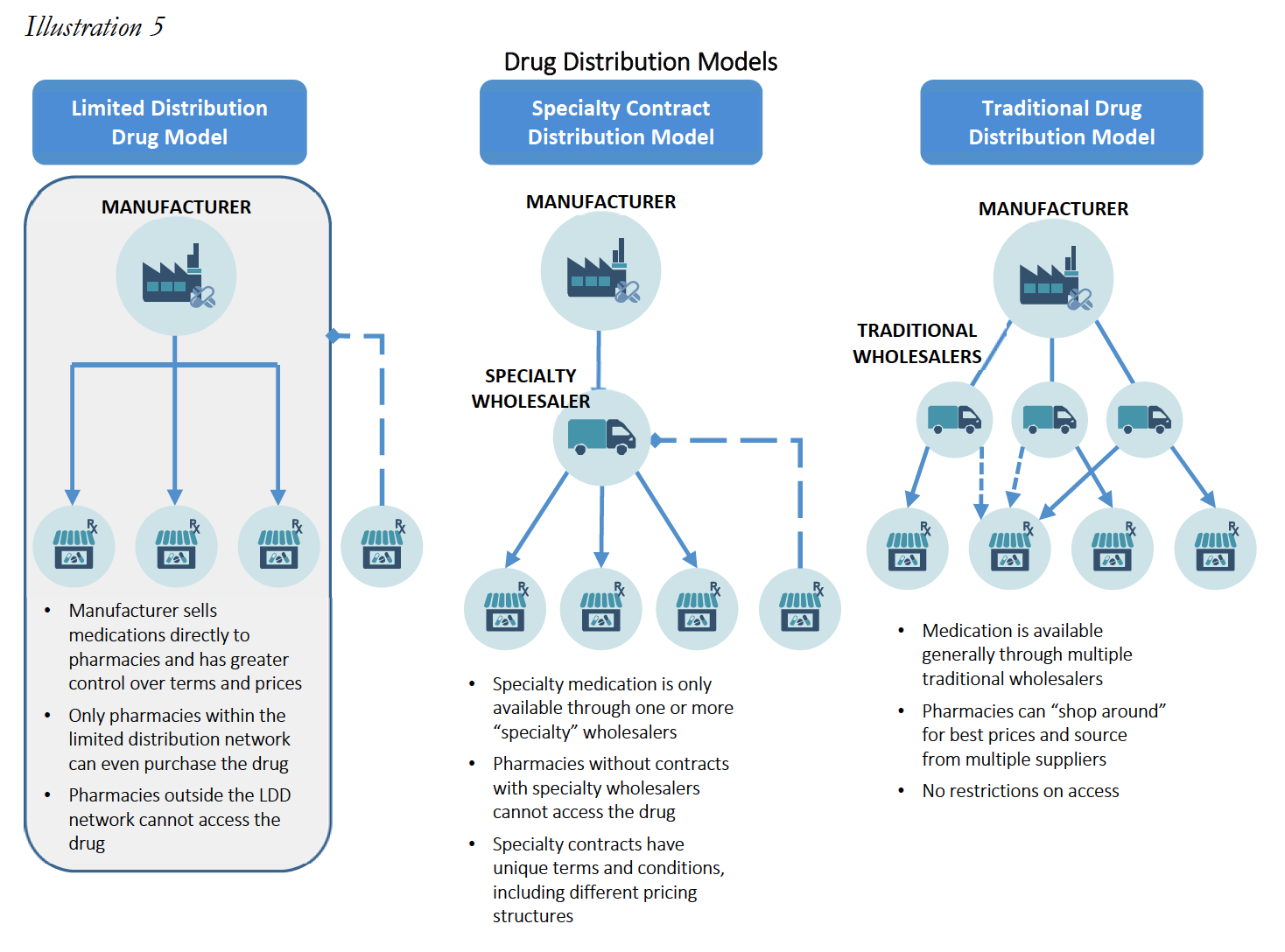

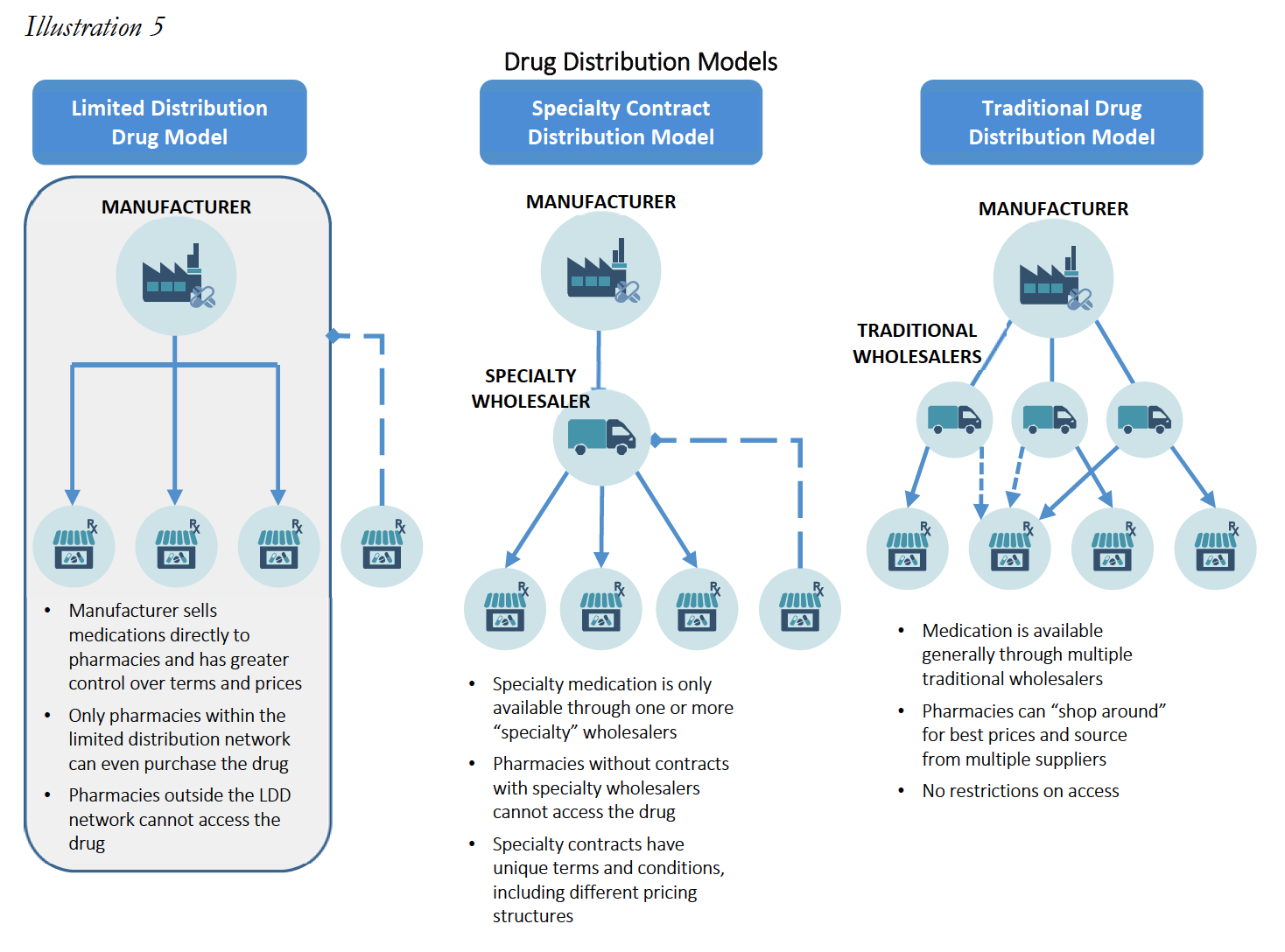

In addition, specialty products differ from their retail counterparts in terms of supply chain and distribution channels. The distribution channels for specialty medications can be widely divided into three categories: (i) specialty medications in a “limited distribution” framework; (ii) specialty medications accessible through a “specialty contract” only; and (iii) specialty medications with traditional accessibility.

Many specialty medications are dispensed through a limited distribution network and are referred to as “limited distribution drugs” or “LDDs.” LDDs could include products that are sold directly from the manufacturer to a select number of specialty pharmacies. Specialty medications acquired directly from the manufacturer represent an estimated 10% of the market. Certain medications are dispensed in this limited fashion for a multitude of reasons, including a need for special handling (i.e. medications that require temperature controlled transportation), requirement for manufacturers to maintain data regarding patient receipt and utilization (i.e. medications that are subject to an FDA Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (“REMS”)), and overall marketability of dispensing information (i.e. utilization of dispensing data to evaluate distribution strategies). The distribution network of a single LDD could be so constrained that it is available only from one or two Specialty Pharmacies nationwide. Often, even the PBM-owned specialty pharmacies do not have access to specific LDDs. LDDs often have higher cost of handling and even lower margins, as compared to other specialty and retail medications.

Other specialty medications may not be distributed directly from manufacturers, but nevertheless are still distributed in a limited fashion as compared to widely accessible medications (such as retail brand and generic medications like Pfizer’s Lipitor or generic omeprazole). These medications typically require access to specialty medication wholesalers/distributors or through a large wholesaler’s specialty contract. Access to this subset of distribution contract is not widely available and include distributors such as ASD Healthcare, Oncology Supply or Besse Medical (all three owned by AmerisourceBergen Corp.), McKesson Specialty (owned by McKesson, Corp.), CuraScriptSD (owned by Express Scripts, Inc.), and Specialty Solutions (owned by Cardinal Health Corp.) This marketplace is highly concentrated in the three largest drug wholesalers, AmerisourceBergen, Corp., Cardinal Health, Corp. and McKesson, Corp. with estimated shares of the specialty distribution market of 34%, 41% and 19%, respectively.

Lastly, many drugs categorized as specialty medications by PBMs and/plan sponsors are more widely available through the same distribution market as retail medication. These can include medications such as Humira and Enbrel. Medications acquired through the standard distribution chain may still be unable to be dispensed by retail pharmacies that do not participate in the specialty pharmacy network, depending on the plan sponsor, or may also be subject to different credit and pricing terms.

These alternative distribution strategies limit a Specialty Pharmacy’s ability to “shop around” for lower acquisition costs, and reduce a Specialty Pharmacy’s leverage to negotiate with wholesalers and manufacturers for lower prices. As such, specialty products are not only generally much more expensive as compared to retail drugs (sometimes upwards of $30,000 for a 30-day supply), but the available margins or mark-ups for the products are often much lower than retail drugs, with most specialty products having margins no greater than 6%. These smaller profit margin percentages are often a function of the fact that specialty medications tend to be very expensive, so a smaller percentage margin is more acceptable. As set forth in greater detail below, small margins combined with higher drug costs means that percentage-based DIR Fees often eliminate any profit and put Specialty Pharmacies into the red, driving Specialty Pharmacies out of the Medicare Part D marketplace. This has the effect of decreasing competition for PBM-owned specialty pharmacies and ultimately increases Medicare’s drug spend, all while restricting medication access and limiting beneficiaries’ freedom of choice. Where these practices push out Specialty Pharmacies that have access to LDD, it could even create a serious patient care crisis, where such restricted medications are simply unavailable in the marketplace to certain beneficiaries.

Mark-ups between what Specialty Pharmacies acquire drugs for versus the benchmark prices at which they are reimbursed by PBMs (typically a function of AWP minus a certain percentage, or WAC13 plus or minus a certain percentage) often range between less than 1% up to 6%. Meanwhile, the mark-ups for retail drugs range from 10% to 30% for brand drugs and can range from 30% to over 1,000% for generics. These differences in distribution frameworks and profit margins pose real difficulties for Specialty Pharmacies once after-the-fact percentage-based DIR Fees are introduced.

In this vein, Specialty Pharmacies often times dispense medication with only a 2% to 5% gross margin to begin with, thus, a retroactive DIR Fee of 3% to greater than 5% may not just eat up their profits, it may (and often does) put the Specialty Pharmacy underwater entirely. These economics present dire realities for Specialty Pharmacies, even if they can manage to obtain the best performance score (and in turn, lowest minimum DIR Fee) possible.

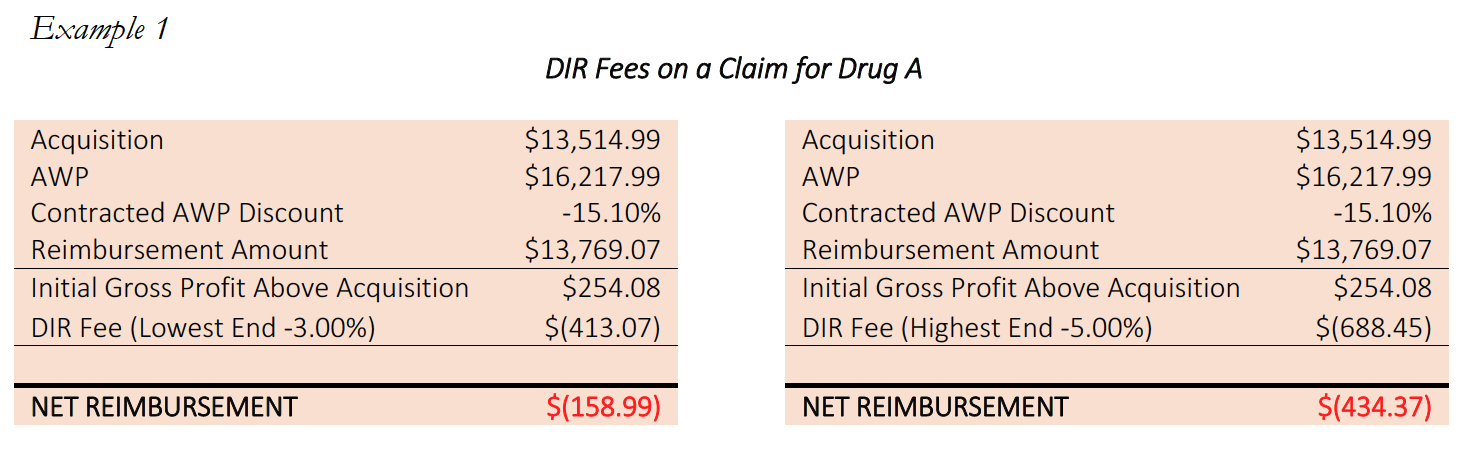

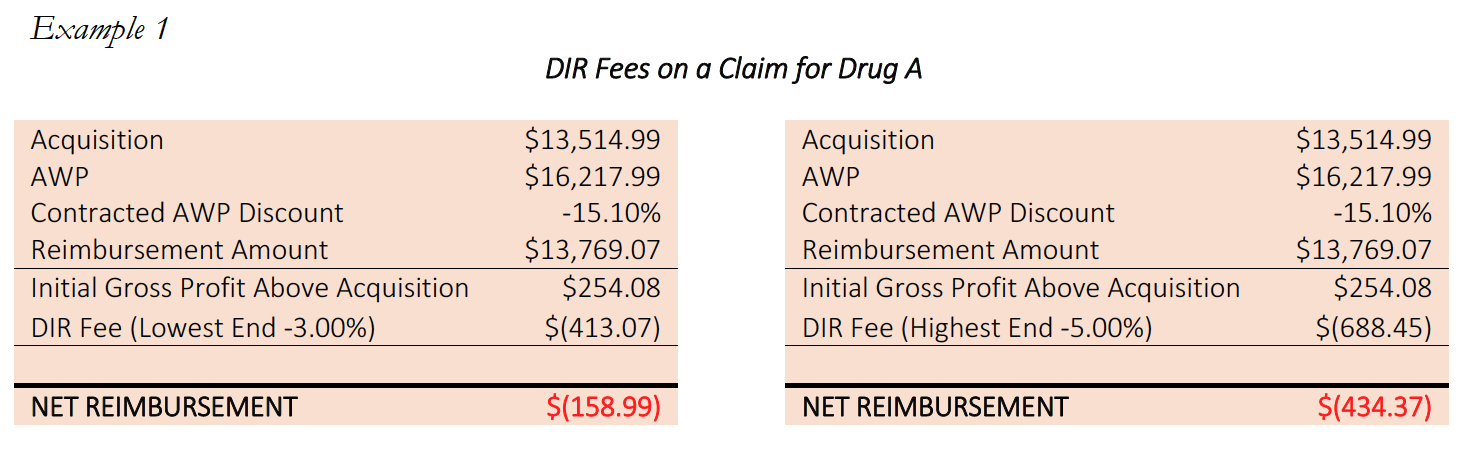

Consider the below example of a Specialty Pharmacy dispensing Drug A15, an oral medication prescribed for the treatment of lung cancer for a Medicare Part D participant.

In the above example, every Specialty Pharmacy losses money on every claim for Drug A. With per claim DIR Fees of up to $688.45, the best the Specialty Pharmacy can hope for is to cap their losses at $158.99 per claim. With this reimbursement, the Specialty Pharmacy is operating at negative margins of between -1.2% and -3.2%. This is before taking into account any costs for overhead, such as payroll, professional fees, and rent, let alone the unique and high-touch services Specialty Pharmacies provide.

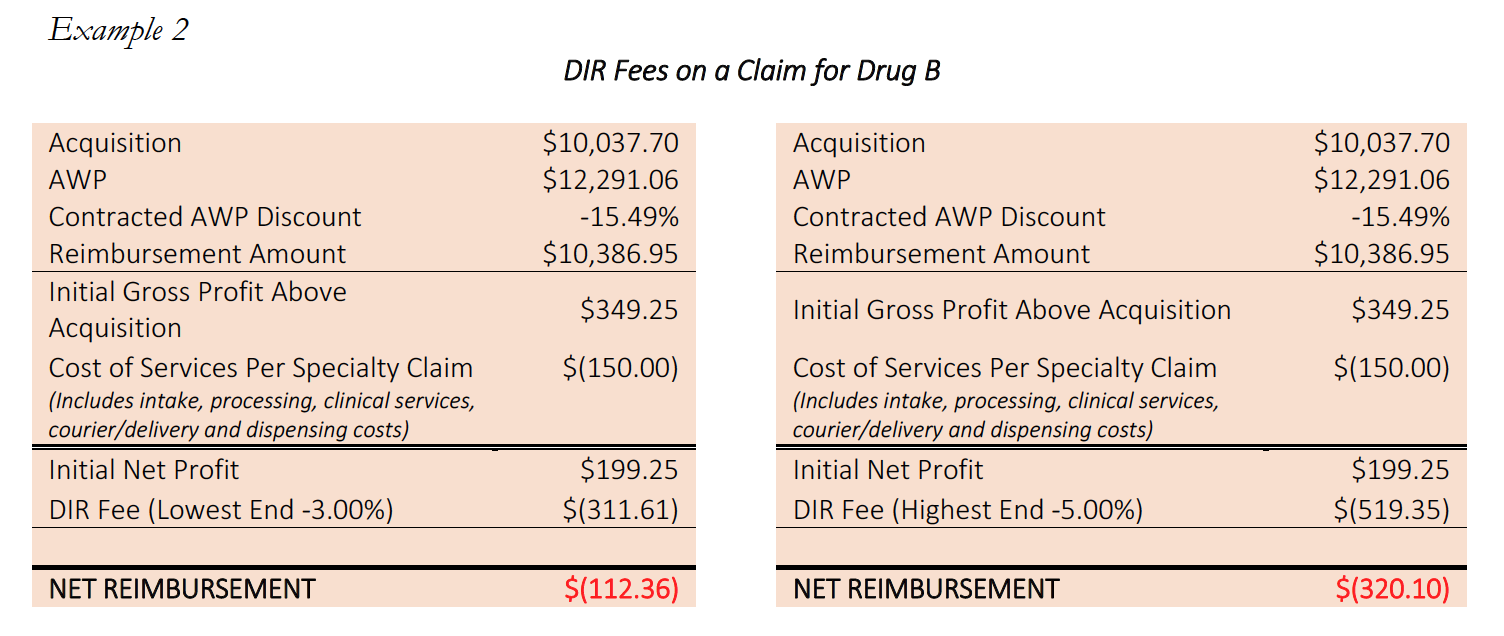

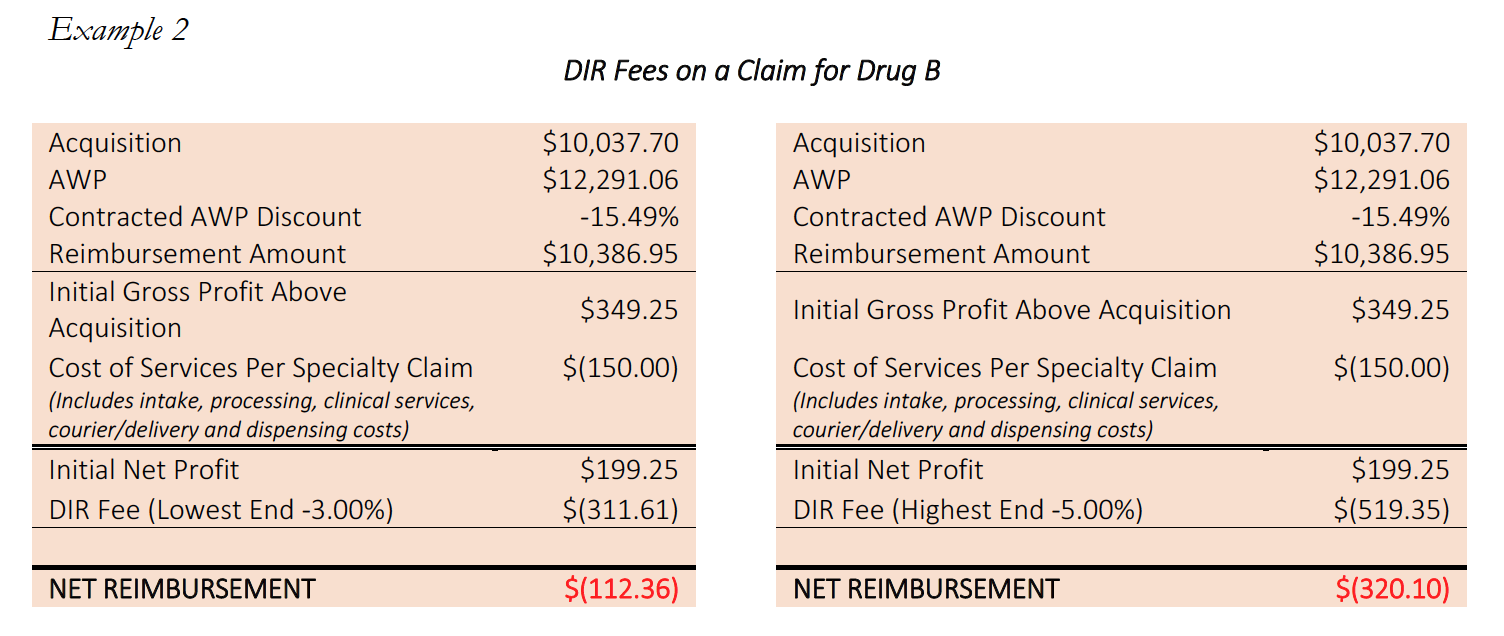

The economics of these reimbursements are particularly egregious for LDDs, to which large chain pharmacies and even many PBM-owned specialty pharmacies have no access, and which often require substantial additional administrative and clinical services as part of the dispensing process. By way of illustration of actual harm to Specialty Pharmacies, consider the following example involving a prescription for Drug B, a “high-touch,” life-supporting oral oncolytic, classified as a limited distribution drug.

These “high touch” services provided by Specialty Pharmacies are critical and necessary, and are what set Specialty Pharmacies apart in functioning as high-level healthcare providers. It can require several man-hours per fill in order for Specialty Pharmacies to process and dispense these medications to their patients. These services could include enhanced patient consultation, obtaining additional information from the prescriber (including clinic notes and records), consulting with nursing staff, completed REMS program reporting, sensitive packaging based on special medication, and finding charitable funding support for patients in financial need. Often times, many of these services are required as part of the Specialty Pharmacy’s mandatory accreditation in order to receive licensing, access to drugs or admission to payor and PBM networks. By creating a reimbursement system that puts Specialty Pharmacy below water – particularly on LDDs to which PBM-owned pharmacies do not have access – PBMs are essentially shifting the financial liability for providing services ancillary to filling the prescription to independent Specialty Pharmacies, forcing them to do it at a loss or not at all. In short, Specialty Pharmacies are losing money treating the most vulnerable Medicare patient population, directly as a result of PBM imposed DIR Fees.

Importantly, however, the disproportionate negative impact on Specialty Pharmacies created by DIR Fees is not limited to LDDs. Many other specialty medications and products that are subject to an open distribution model, such as Enbrel, Humira or Harvoni, are subject to the excessively high and unreasonable percentage-based DIR Fees, putting Specialty Pharmacies underwater and threatening their ability to continue to provide these critical, high touch, patientcentric services to drive patient compliance, persistency and optimal clinical outcomes.

What’s worse, for Specialty Pharmacies, a higher percentage of their patient population receive high-cost specialty medications, which leads to DIR Fees having a disparate impact on accredited Specialty Pharmacies as compared to other providers.

This is illustrated with an example. Consider two pharmacies, Pharmacy A, a retail pharmacy, and Pharmacy B, a Specialty Pharmacy who has devoted substantial resources to invest in Hepatitis C therapies, clinical protocols and treatments, and who has forged relationships with prescribing physicians and Hepatitis patient groups alike. If Pharmacy A fills 100 prescriptions in a given month, 98 of the prescriptions would likely be for traditional retail medications at $100.00 per fill, and perhaps 2 of the prescriptions would be for Drug Y, a specialty oral hepatitis medication for the treatment of Hepatitis C, for $25,000 per fill. Meanwhile, when Pharmacy B fills 100 prescriptions in a given month, it is possible that 98 of them would be Drug Y, and only 2 of them might be traditional retail medications.

If both Pharmacy A and B are assessed the same DIR Fee of 4.5%, Pharmacy A’s total DIR Fee clawbacks would be $2,691.00, while Pharmacy B’s clawbacks would be $110,259.00. Of course, if the DIR Fees were a flat fee, or were capped at a rate in line with other PBMs, the total DIR Fees for both pharmacies would only be $500.00. In either event, however, these fees are based on performance and quality measures irrelevant to specialty pharmacy outcomes, and regardless of the formula used to calculate the fees, these fees are levied with no added value delivered by the PBM to the Part D beneficiary or the Medicare Part D program.

These trends are only more pronounced in cases where Specialty Pharmacies have access to limited distribution drugs. In those cases, Specialty Pharmacies receive an even higher percentage of prescriptions for those limited therapies, to which they are often one of only a handful of pharmacies with access to sell the product, and such Specialty Pharmacies regularly receive referrals from other providers (including PBM-owned specialty pharmacies who do not even have access to certain medications). Penalizing Specialty Pharmacies whose clinical systems are designed to handle rare medications, so that PBMs can reap staggering profits on DIR Fees, is unconscionable and ultimately hurts Medicare patients and the Medicare system generally.

In addition, many of the conditions requiring specialty medications tend to have higher incidences in the Medicare Part D population, where performance based DIR Fees have been most heavily implemented. For example, cancer and rheumatoid arthritis are conditions with a variety of high cost specialty medications available in the marketplace, and which have a higher incidence among seniors. Medicare patients have a much higher chance of having these diseases than younger patients covered by commercial policies, where these performance-based DIR Fees do not generally apply.

These factors only serve to compound an already precarious and unsustainable position for Specialty Pharmacies’ ability to serve patients and provide the critical support services in certain Medicare Part D networks. The severe, negative economic impact on Specialty Pharmacies caused by DIR Fees compromises the access and choice of our most vulnerable patient population – Medicare Part D beneficiaries. If Specialty Pharmacies are forced to discontinue providing these support services and specialty medications to Medicare Advantage and Medicare Part D participants, Medicare beneficiaries will not have access to a broad selection of willing providers to service their critical medication needs. As a result, DIR Fees may effectively steer Medicare beneficiaries toward a small subset of PBM and payor-owned specialty pharmacies with few incentives to achieve optimal clinical outcomes and patient service. As noted below, this narrowing of Medicare Part D Specialty Pharmacy networks circumvents the intent of the Medicare Any Willing Provider Provisions and seriously threatens beneficiary access and choice.

Case Study: Flat Fee DIR Fees vs. Percentage Based DIR Fees

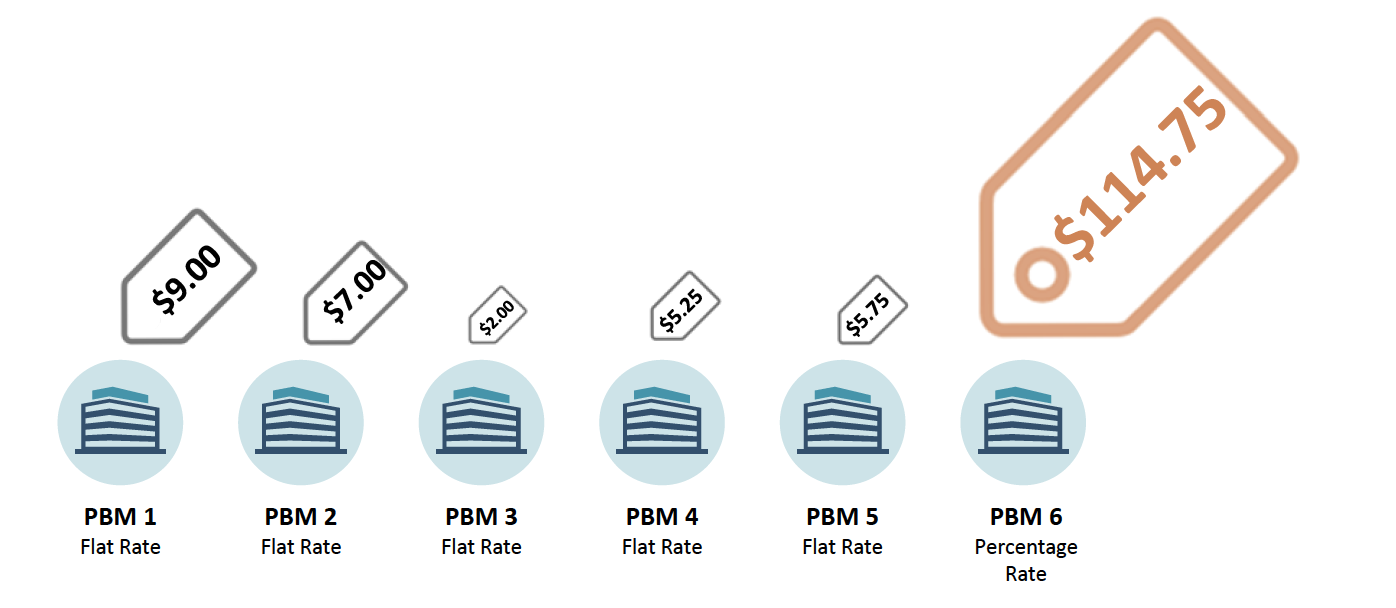

Without commenting on the propriety of any one format, or even of any DIR Fee construct as a whole, it is important to recognize that percentage‐based DIR Fees are not the only format in existence in the Medicare Part D marketplace. Many PBMs employ DIR Fee programs that encompass a fixed dollar amount per claim. Utilizing information across the pharmacy industry it is clear that the utilization of percentage based DIR Fees ultimately has a disproportionate impact on Specialty Pharmacies. An industry wide example of different PBM programs illustrates the disproportionate impact of percentage based DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacies. The chart below illustrates the enormous fee associated with percentage‐based DIR Fees as compared to Flat Rate DIR Fees.

Percentage‐based DIR Fees result in assessments against Specialty Pharmacies nearly 20‐times the average of other industry flat‐rate DIR Fees. Of note, with the average cost of a generic retail drug is a little more than $280 per year. A 4.5% DIR Fee on a generic retail medication would result in a clawback of approximately $12.60, or 1.06 per prescription, a number more in line with other flat rate DIR Fees. The flat rate DIR Fee imposed on a generic drug illustrates and further confirms the inappropriateness of percentage‐based DIR Fees in the context of Specialty Pharmacy.

Moreover, the disproportionate impact on Specialty Pharmacies is often larger than the average listed above, as many Specialty Pharmacies often dispense much more expensive products. For example, Specialty Pharmacies dispense certain medication with costs above $30,000. The DIR Fee for these medications are well above $1,000 per prescription per month when calculated on a percentage basis as oppose to fees that max out around $9.00 under flat rate DIR Fee programs with other PBMs. This is nearly a 20,000% increase over the average DIR Fees in flat fee programs.

4.2 Inapplicability of Performance Metric Criteria to Specialty Pharmacies

The disparate impact of DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacies goes beyond solely the economics of percentage-based DIR Fees applied to high-cost specialty drugs. Specialty Pharmacies face a “double whammy” when percentage-based DIR Fees are calculated based on quality metric categories that have nothing to do with the products and services provided by Specialty Pharmacies, and over which Specialty Pharmacies have no ability to influence performance scores. Overall, the quality metric categories, as implemented and applied by PBMs, do not provide an adequate basis of measuring Specialty Pharmacies’ impact on patient care.

Quality metric categories utilized by PBMs to calculate DIR Fee are largely inapplicable to Specialty Pharmacies. In many early DIR Fee programs, PBMs have adopted the CMS Star Ratings System to develop performance metrics. There’s good reason they do this, as PBMs and Part D sponsors themselves receive a financial bonus with the achievement of higher Star Ratings from CMS. As a result, these quality metric categories often include individual patient adherence to certain treatment regimes in specific categories such as: 1) heart disease (Angiotensin-converting enzyme (“ACE”) inhibitors / angiotensin receptor blockers (“ARB”) adherence); 2) treating high cholesterol (statin adherence); 3) managing high blood sugar levels (diabetes adherence). Putting aside the mechanics of how these metrics are calculated (which is a discussion for another day, given the murkiness of PBM contracts), these quality metric categories are primarily retail pharmacy driven, and are largely inapplicable to Specialty Pharmacies as these pharmacies do not focus on the treatment of the few above-mentioned medical conditions.

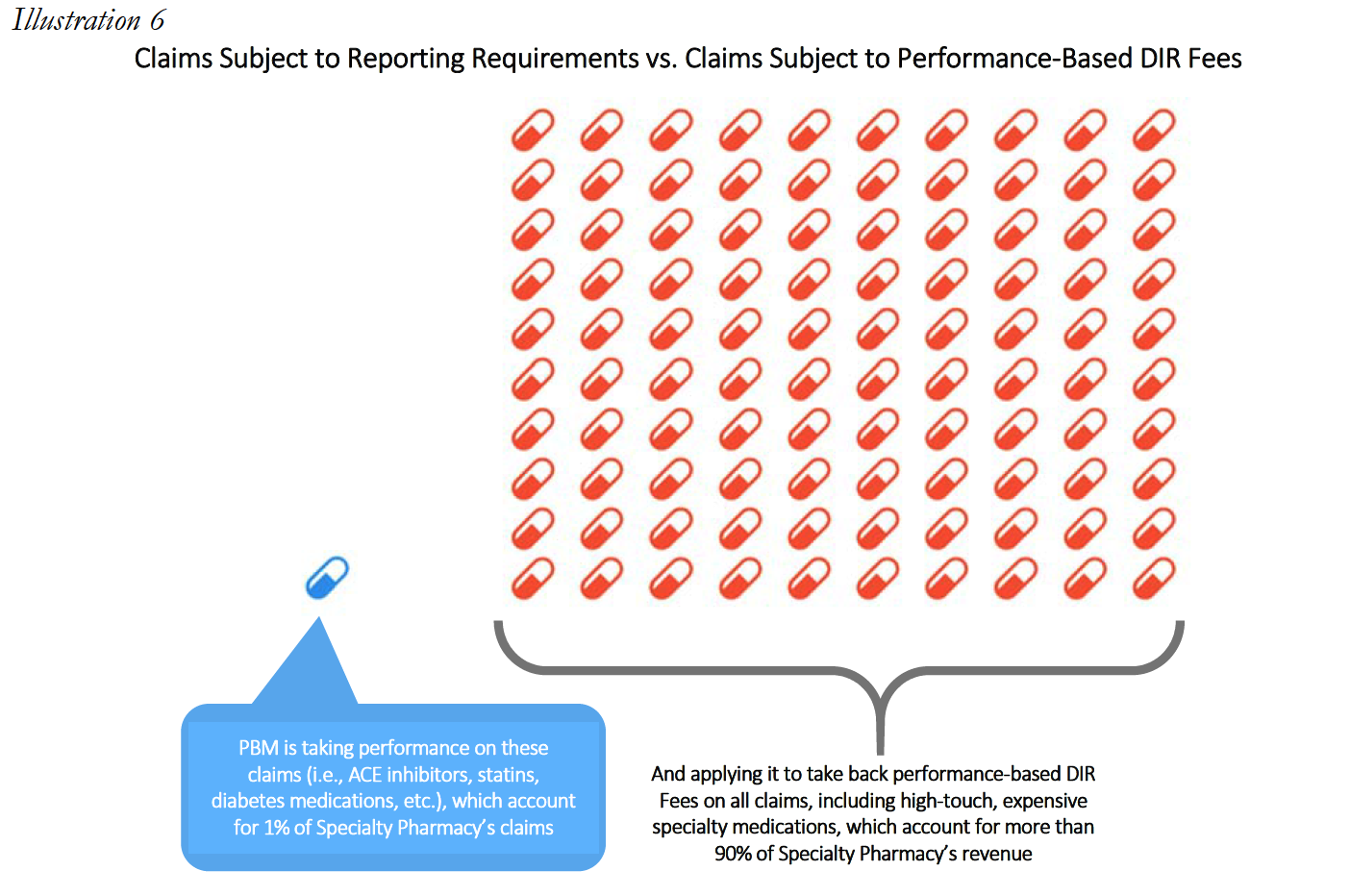

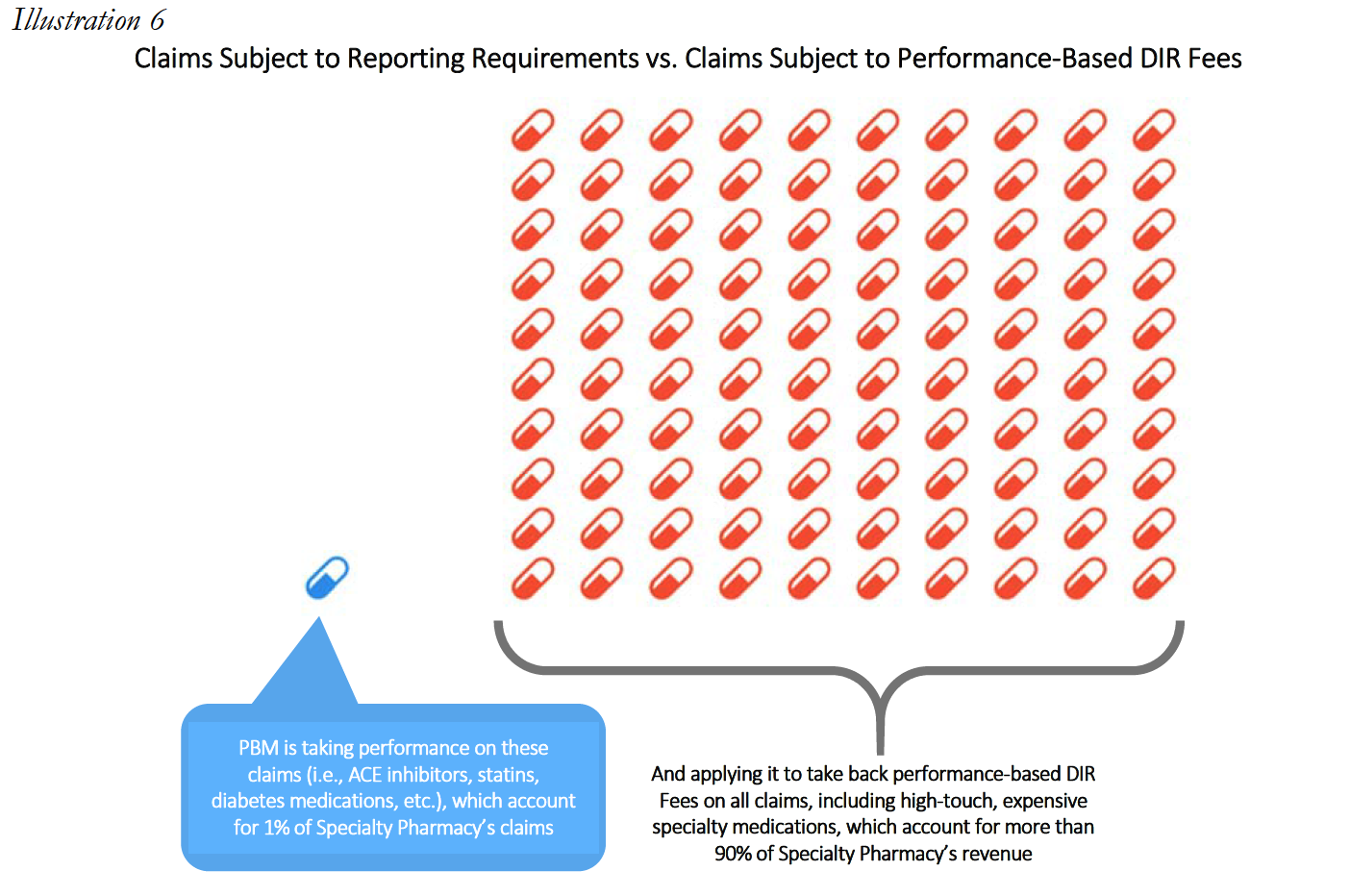

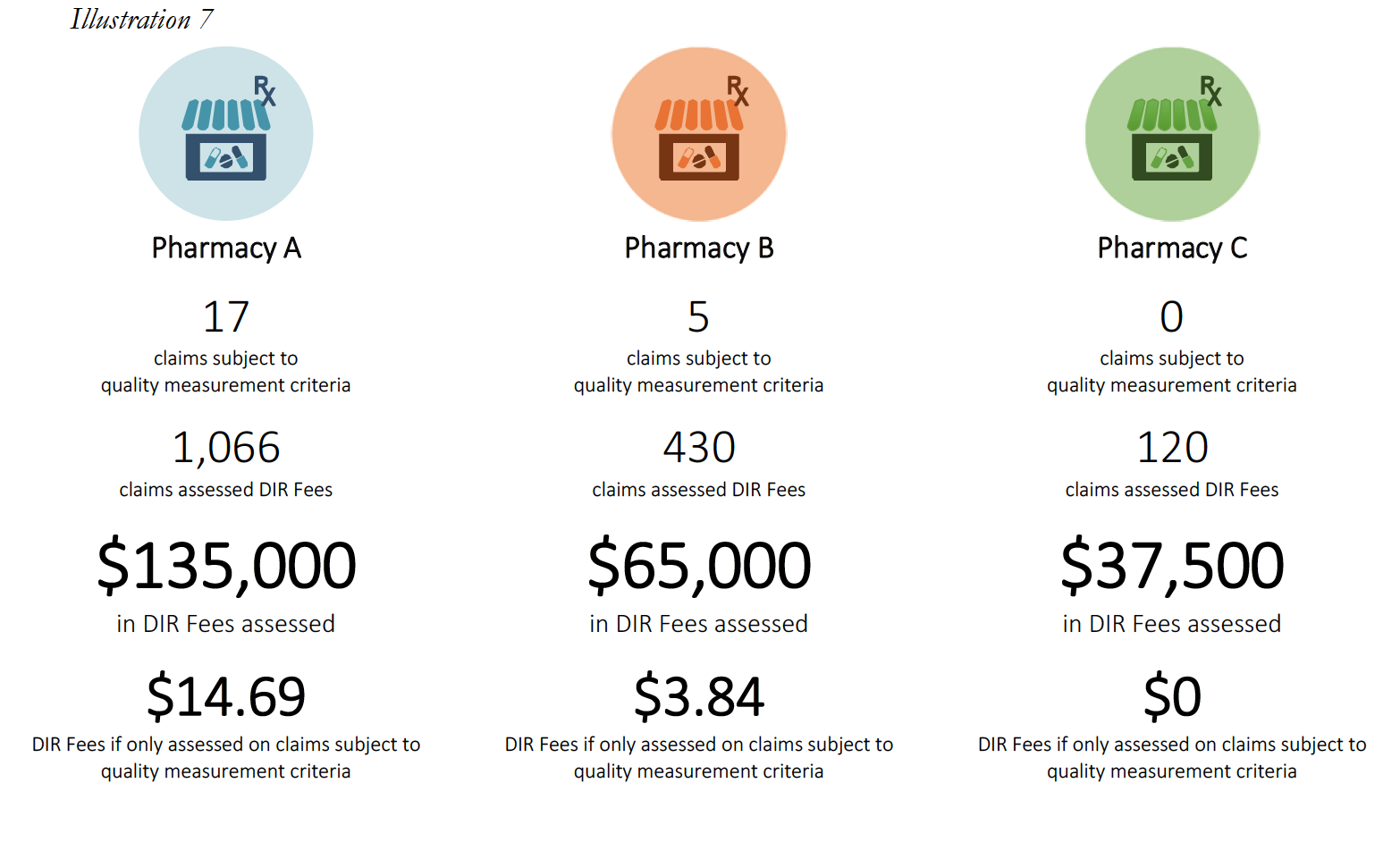

Specialty Pharmacies instead focus on providing medication for the sickest members of the population that face incredibly complex, serious, and often rare medical conditions. The inapplicability of limited quality metric categories is best viewed through a real-life example. During the period of time that Specialty Pharmacy A is reviewed to assess its score of the quality metrics, Specialty Pharmacy A dispensed 1,800 prescriptions. Of those 1,800, only 1% or 18 individual prescriptions fit into the PBM’s above-mentioned performance categories because Specialty Pharmacies do not dispense ACE/ARB, statins, or diabetes medications. Nevertheless, the PBM will assess percentage-based DIR Fees on Specialty Pharmacy A on all 1,800 claims based on “performance” on only 18 claims.

The experiences of Specialty Pharmacy A are not unique within the specialty pharmacy industry.

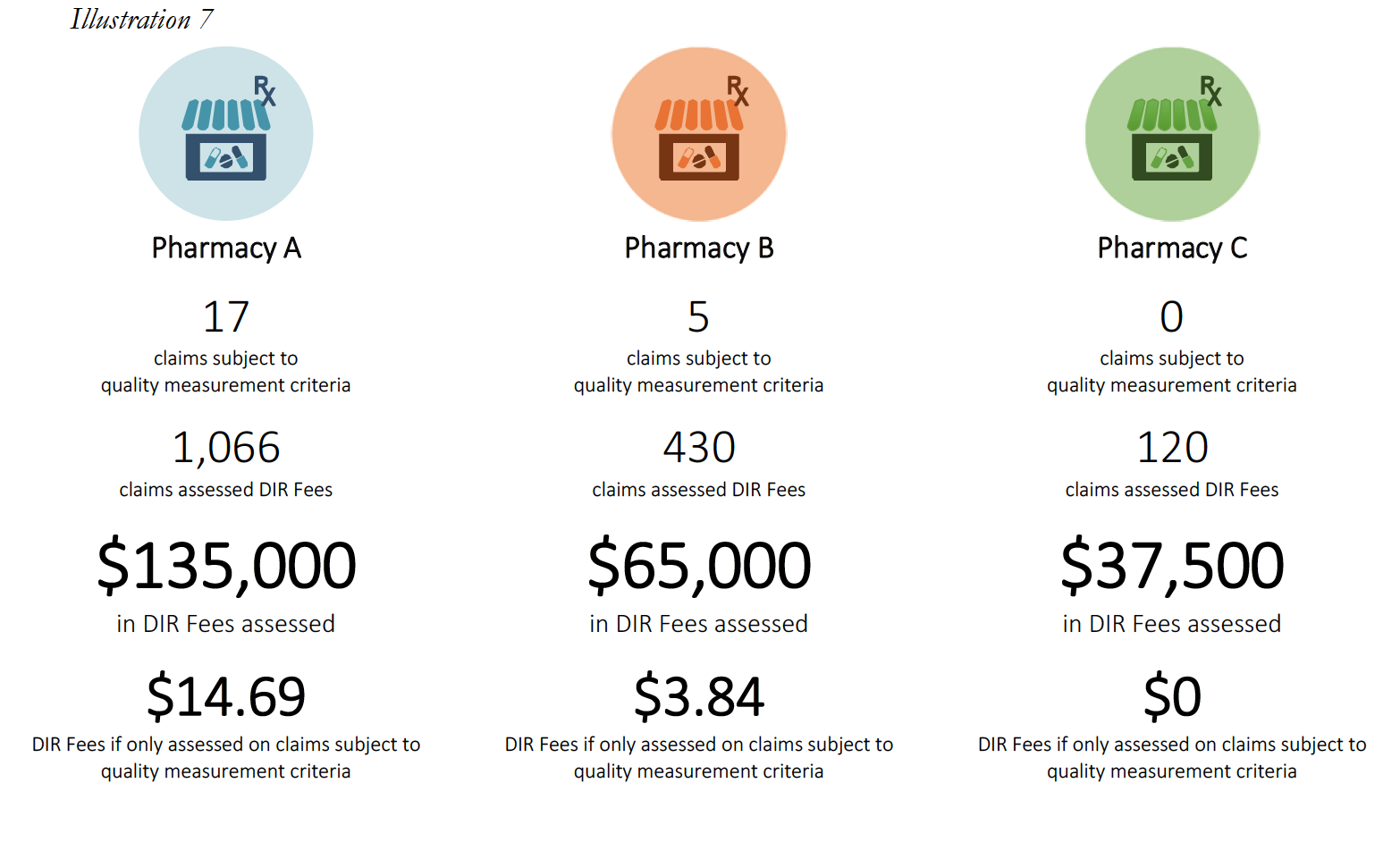

Pharmacy C’s experience in the scenario above raises an important question about what happens when a pharmacy does not have sufficient claims volume in the various performance criteria. Many PBM contracts may state that in such cases, the pharmacy will neither be advantaged nor disadvantaged by this scenario. However, in practice, such Specialty Pharmacies are ultimately assigned the average score for that particular Part D plan and penalized.

This is perhaps the most egregious aspect of how DIR Fees are applied and weighted in the Specialty Pharmacy context. In these situations, Specialty Pharmacies may often find themselves being ascribed the average performance of other pharmacies for the various categories (such as, diabetes adherence), within that particular Part D plan during that assessment period. These categories tend to make up the bulk of the weighting (around 95%) for the performance score, leaving Specialty Pharmacies with control of only minimal components of the performance criteria (such as formulary compliance, which appears to simply list all claims dispensed by a pharmacy in that plan during that time period). This design and application flies in the face of not only the concept that Specialty Pharmacies will neither be harmed nor helped by not having claims in a given category, but also the concepts of overall fairness and equity. In fact, these network average scores often prove to be much less than scores that are or could be obtained by Specialty Pharmacies, who are often best-equipped to obtain positive patient outcomes for the diseases and medical conditions of which each Specialty Pharmacy specializes in.

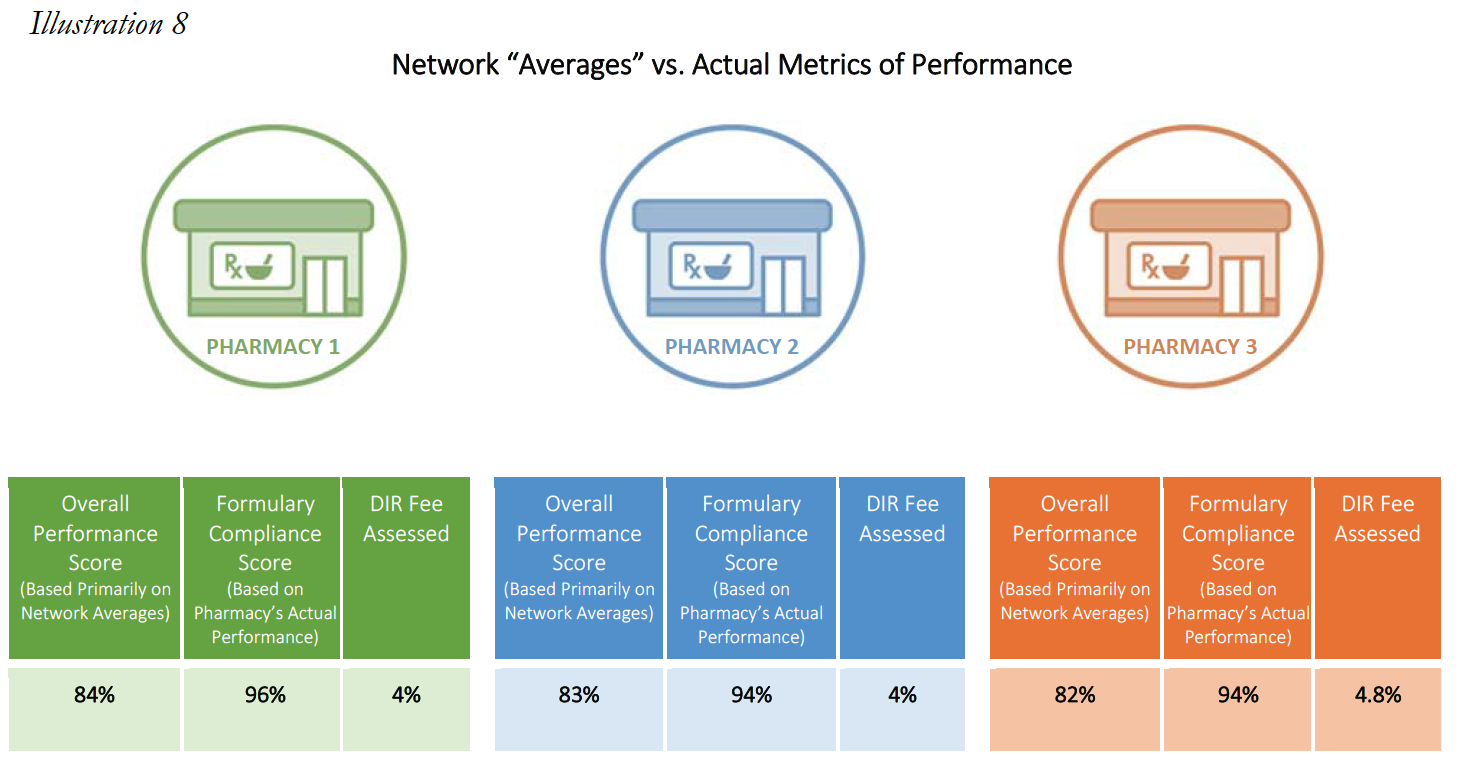

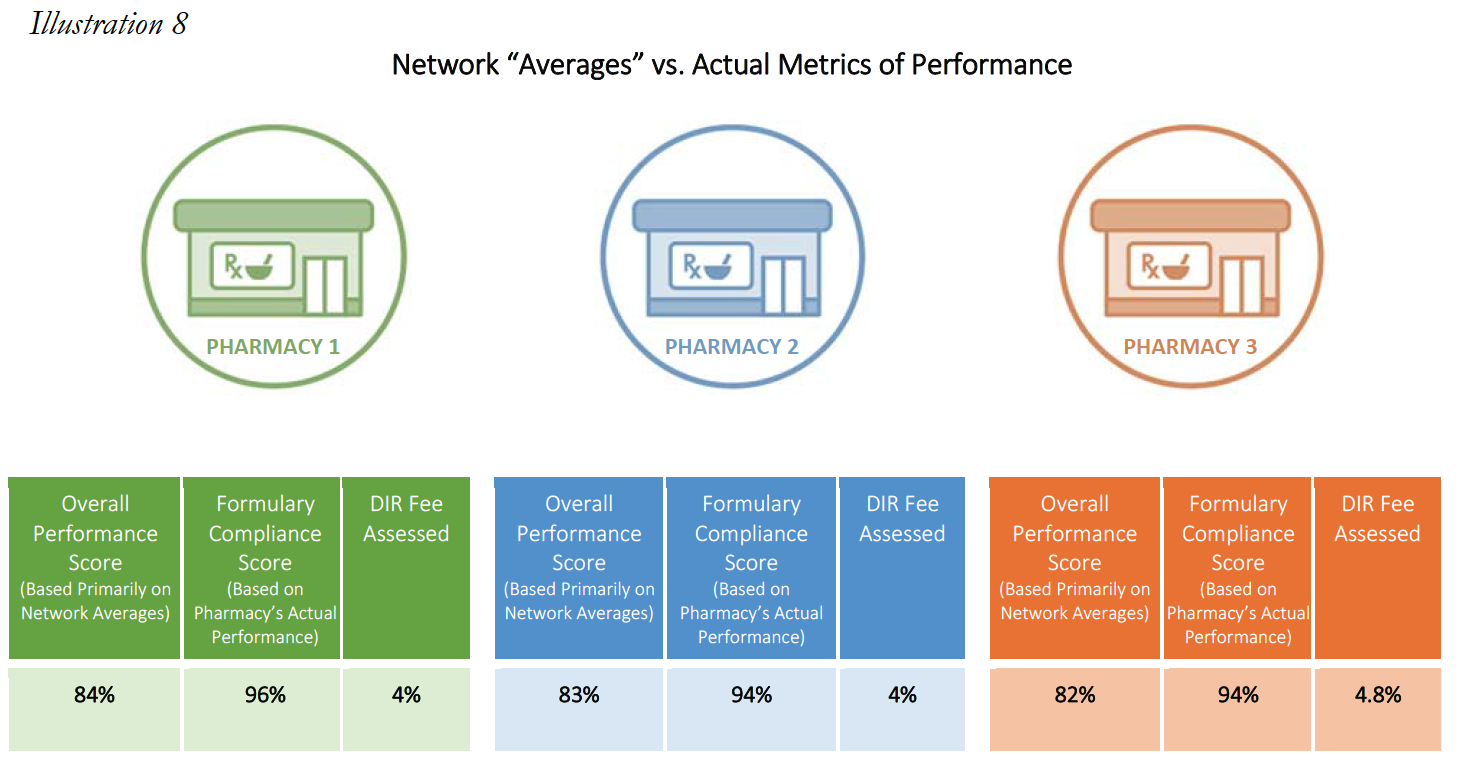

Consider the following three examples of Specialty Pharmacies, who had no claims subject to any of the reporting criteria, except for the Formulary Compliance metric.

In each of the above cases, the Specialty Pharmacies are ascribed a performance score based on the network averages that is substantially lower than the scores the pharmacies did achieve in the Formulary Compliance category that is applicable to their Medicare patient population. As is demonstrated in Pharmacy 3’s example, this Specialty Pharmacy had zero claims in any of the quality metric categories, other than the “Formulary Compliance” metric. As noted, the Specialty Pharmacy scored exceedingly well on those claims, with a score of 94%, but was nevertheless assigned the “average” performance score of all pharmacies in the other quality metric categories, which dramatically reduced its overall performance score to 82%. Thus, the Specialty Pharmacy obtained a score more than 14% higher based on metrics against which it was actually measured. Such a significant improvement in performance scores could put the pharmacy in a different DIR Fee tier altogether, as compared to the 4.80% that the Specialty Pharmacy was assessed. Even the difference of one percentage point in DIR Fee rates (assuming they could even be applied in the first place) could result in decreased costs to some Specialty Pharmacies of hundreds of thousands of dollars in one trimester alone.

Moreover, because the Star Ratings system is essentially a retail pharmacy construct, DIR Fee performance metrics based on this system are focused on retail pharmacy functions, and overlook the superior performance and quality measures demanded and routinely attained by accredited Specialty Pharmacies. For example, while Specialty Pharmacies do not create policies and protocols around maintaining diabetes or statin adherence (since they very rarely dispense those types of products), they do develop and maintain a robust series of procedures and workflows surrounding other quality measures more applicable to specialty pharmacy. These include measurements of Proportion of Days Covered (“PDC”), Drug Safety, Dispensing Accuracy and Patient Satisfaction, just to name a few. These metrics are carefully tracked real-time by Specialty Pharmacies (often as part of their accreditation requirements), and are far better indicators of the performance level of Specialty Pharmacies compared to Star Ratings. Most critically in this regard, however, is the fact that for these measurement criteria, Specialty Pharmacies seek and attain performance rates far in excess of the network average scores they are ascribed through many PBMimposed DIR Fee programs. For example, Specialty Pharmacies routinely strive for and actually meet compliance rates of either 90% or better, 98% or better, or even 99.8% or better. Thus, the performance metrics used by PBMs have no bearing whatsoever on the services and products actually provided by Specialty Pharmacies.

The methods in which DIR Fees are assessed against Specialty Pharmacies are at best puzzling, and at worst illogical and capricious. What’s worse, the method of calculating DIR Fees is completely divorced from the overall purpose of the program: to reward pharmacies for performing well, and to punish pharmacies for performing poorly. Rather, these performance-based DIR Fee programs have devolved into economically punishing pharmacies for the poor performance of their competitors.

The Negative Impact of DIR Fees Is Not Limited to Specialty Pharmacies as DIR Fees Push Medicare Part D Beneficiaries into the Coverage Gap Prematurely and Increase Overall Costs to Beneficiaries and the Government

Contrary to many recent statements in the marketplace and by the PBM lobby, the expansion of DIR Fees has had a substantial negative impact on both Medicare beneficiaries and the Program as a whole. As confirmed in recent CMS studies, DIR Fees ultimately shift financial liability from the Part D Plan Sponsor to the patient, then ultimately to Federal government, through Medicare’s catastrophic coverage framework. The shifting of financial liability away from the Part D Sponsor and to Medicare and the patient is even more pronounced in the context of specialty medications. An understanding of this phenomenon requires first an understanding of the Medicare Part D coverage breakdown.

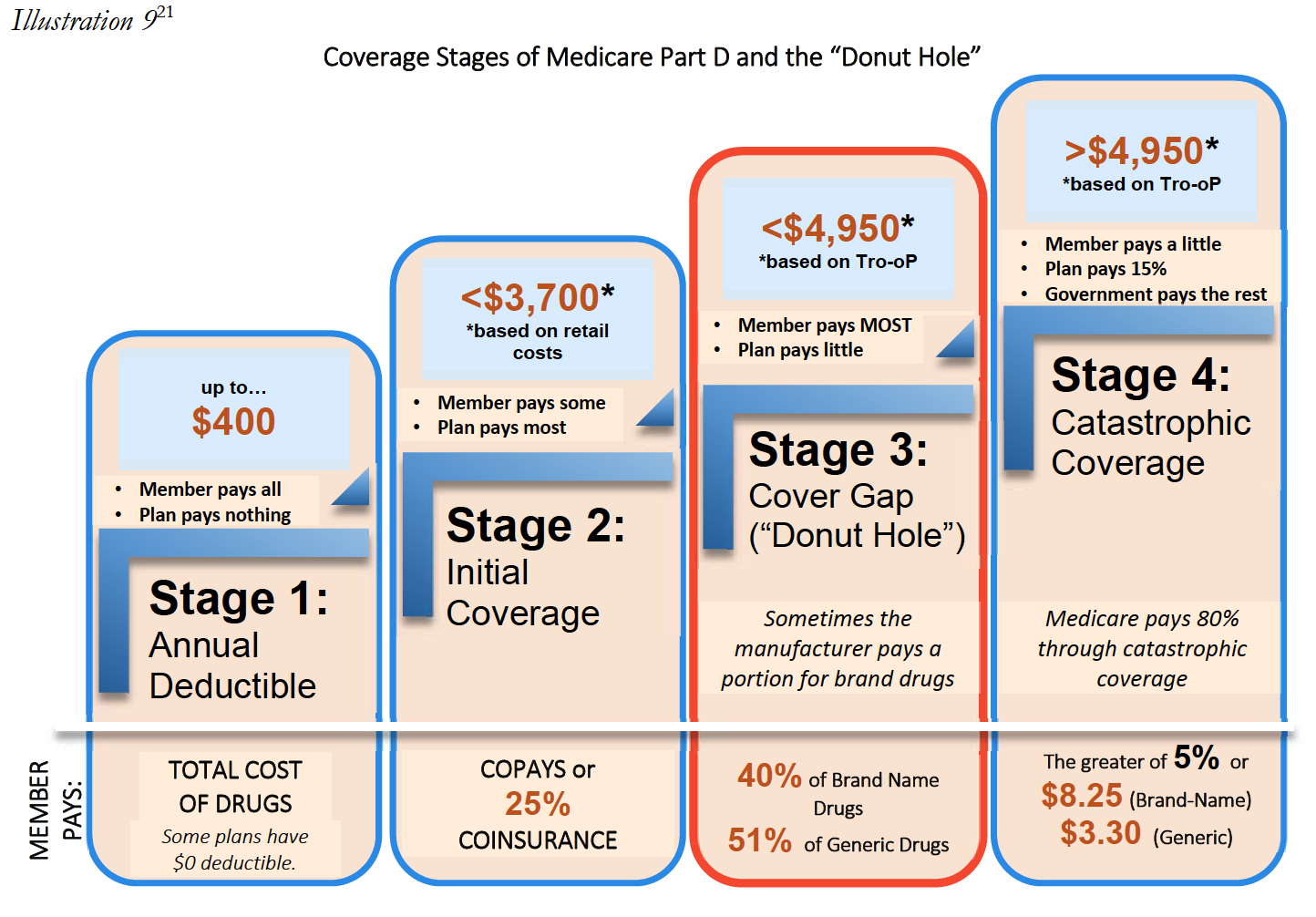

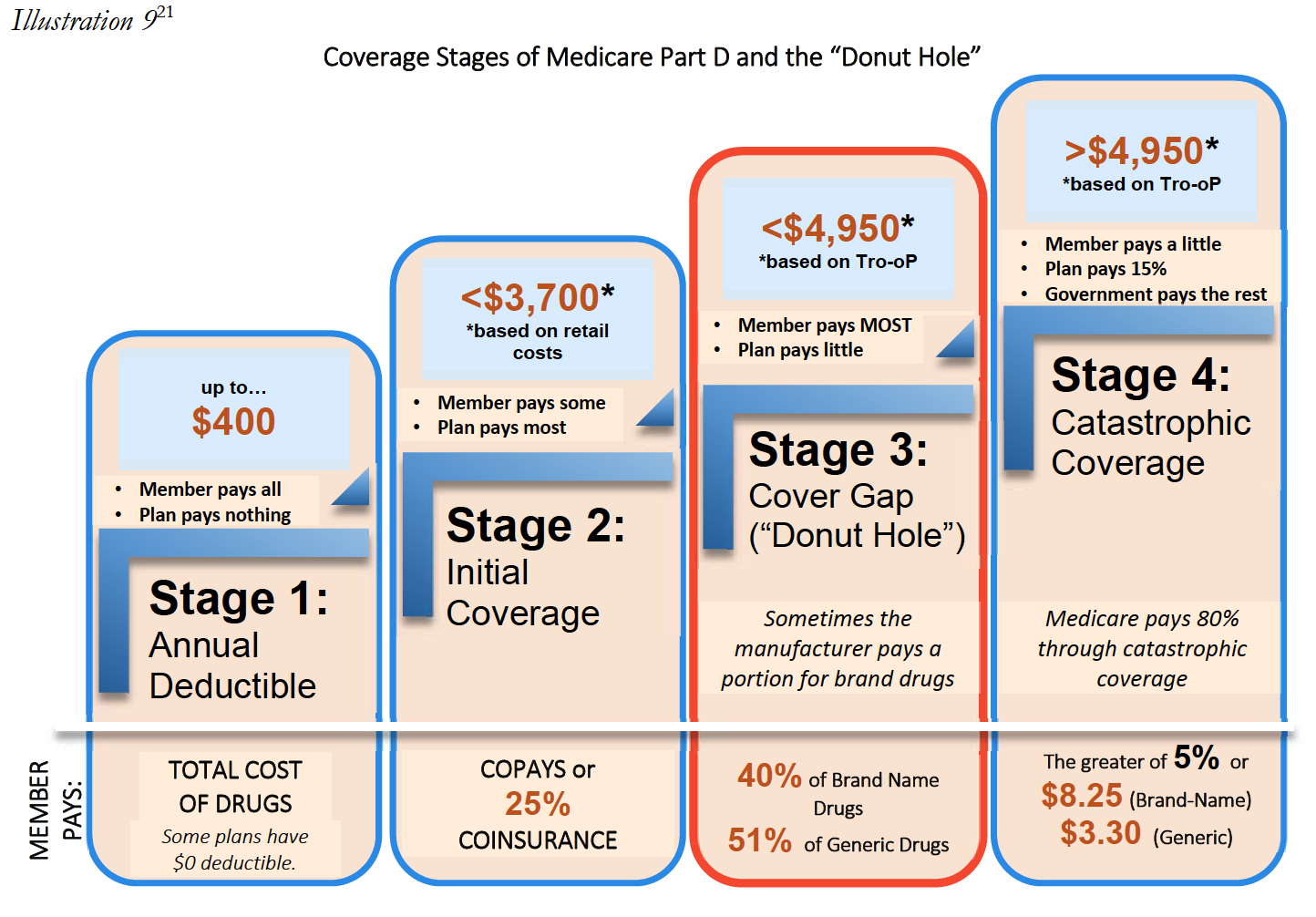

Most Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit plans have three stages: (1) initial coverage, (2) the coverage gap, or “donut hole,” and (3) catastrophic coverage. Each stage has different limits or thresholds, which are updated from year-to-year. In 2017, the initial coverage for a Medicare Part D beneficiary was $3,70019. As illustrated in detail in the table below, this means that for the first $3,700, the beneficiary, under most Part D plans, will have minimal out-of-pocket costs, which are usually limited to the beneficiary’s deductible (in plans that have a deductible component), copayments, and potentially coinsurance for their prescription drugs (coinsurance is often 25% of the drug cost). Once the beneficiary and the Medicare Part D plan spend $3,700 collectively on covered drugs, the beneficiary enters stage 2, known as the “coverage gap” or “donut hole.” When a Medicare beneficiary is within the “donut hole,” they are responsible for up to 40% of the plan’s cost for brand-name drugs, and up to 51% of the plan’s cost for generic drugs (importantly, Part D Plan Sponsors are only responsible for 10% of brand-name medications and 49% of generic medications in the donut hole, as compared to 75% during the initial coverage stage20). Thus, the Part D Plan Sponsor has a financial incentive to move Medicare beneficiaries into the Donut Hole. A Medicare beneficiary remains in the “donut hole” until the beneficiary and Part D plan have spent $4,950 collectively in 2017. Once the beneficiary and plan’s cost exceed $4,950, the beneficiary enters stage 3, “catastrophic coverage.” In stage 3, a beneficiary’s out-of-pocket costs greatly decrease, as they are capped at either 5% or $3.30 (whichever is greater) for generic or preferred medications, and 5% or $8.25 (whichever is greater) for all other drugs. Most critically, the Part D Plan Sponsor’s share decreases to 15% during the catastrophic coverage stage – this is 5-times less than their responsibility during the initial coverage stage. This three-stage process is illustrated in Illustration 9 below.

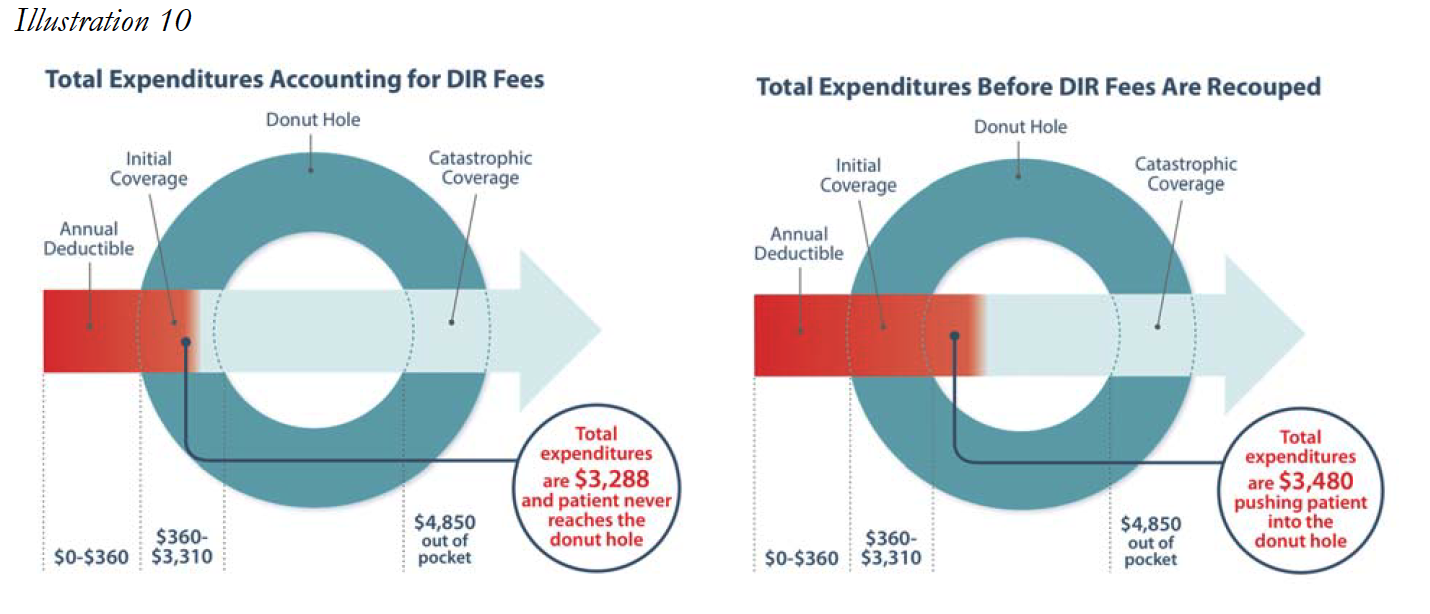

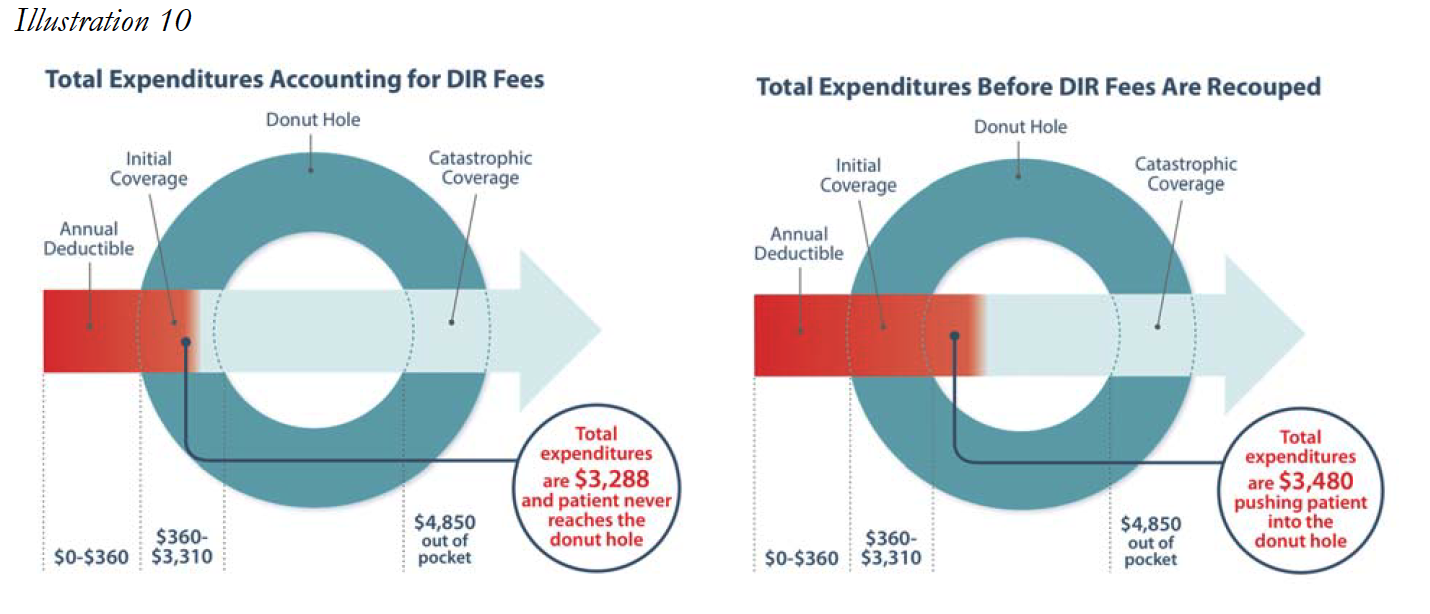

Ultimately, the post point-of-sale imposition of DIR Fees may result in Medicare beneficiaries entering the donut hole prematurely. For example, Patient A receives a prescription drug once a month with a negotiated price of $290 per month. Patient A will enter the “donut hole” after twelve fills, and will thus be responsible for an increased level of cost sharing until Patient A reaches catastrophic coverage limits. If, however, the negotiated price for the drug charged at the point of sale had reflected a 5.5% DIR Fee (instead of the PBM subsequently assessing such fee on the Specialty Pharmacy after the Medicare beneficiary enters the Donut Hole), the costs charged to Patient A would dramatically decrease. In fact, Patient A would have never entered the “donut hole” in the first place. This is shown in the illustration below based on 2016 limitations.

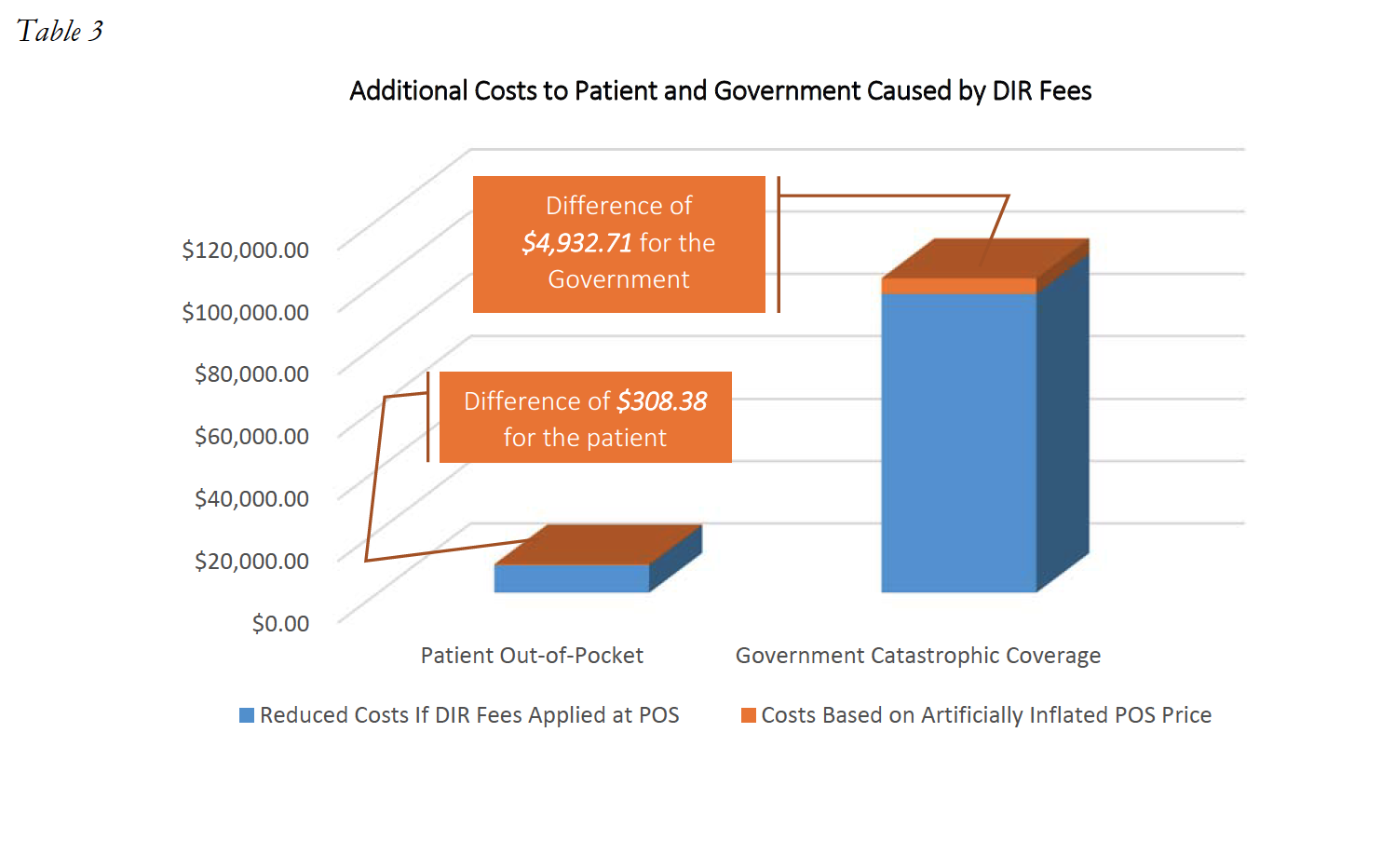

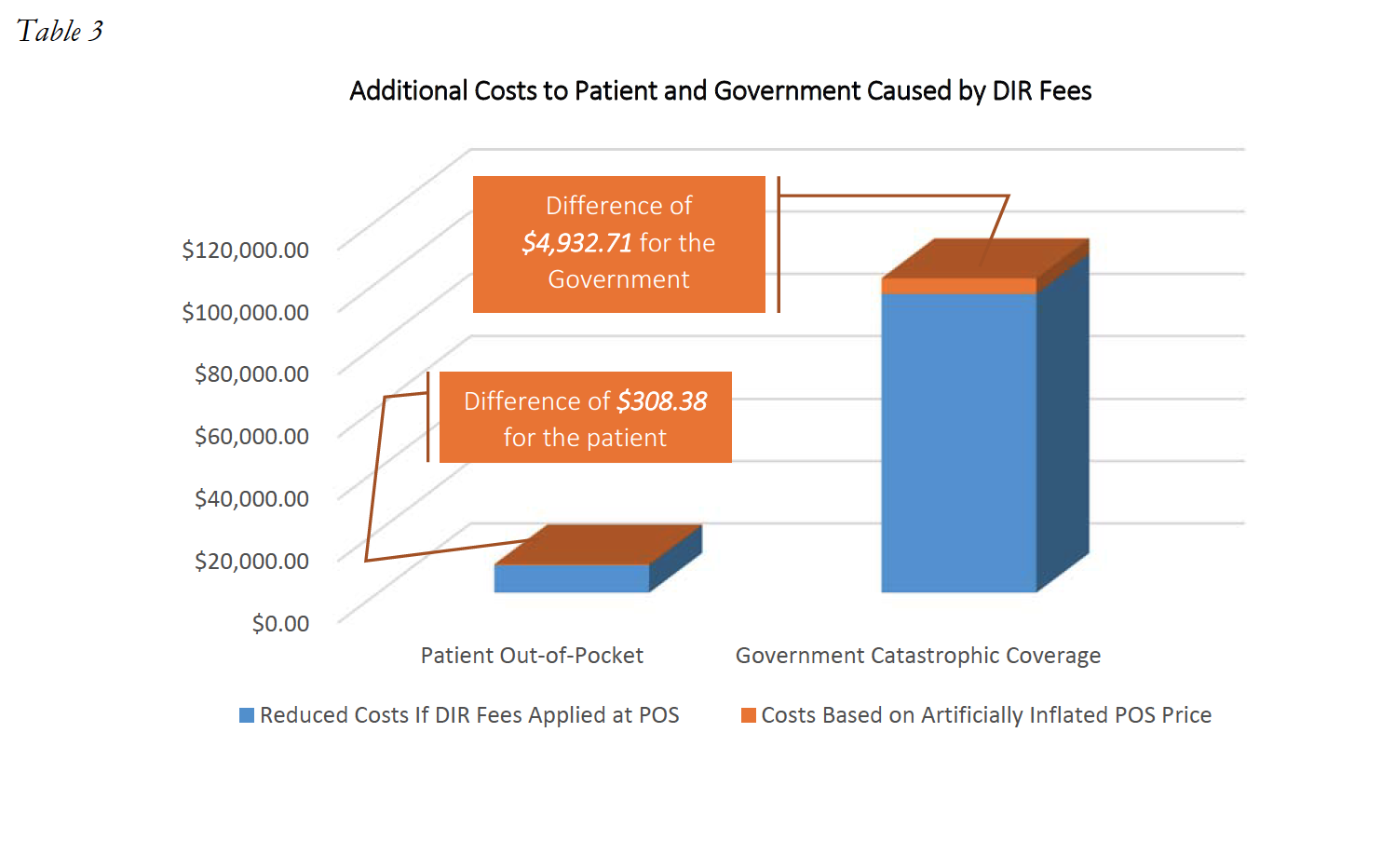

Next, consider the impact a 4.6% DIR Fee would have on Patient A’s out-of-pocket expenses. Instead of Drug Y costing Patient A and her Part D Plan $11,170.90 each month, the DIR Fee being charged at the point of sale would result in the actual price of the drug being $10,657.04, a difference of $513.86 per month. Accordingly, Patient A’s first-fill would cost approximately $3,042.20, and each subsequent month Patient A would be responsible for approximately $532.85. Patient A’s total out-of-pocket expenses for the year would amount to $8,903.55. Thus, Patient A paid an additional $308.38 throughout the course of the year out-ofpocket because Patient A’s cost-sharing amounts were based on the drug’s cost prior to the PBM’s imposition of DIR Fees. In other words, Patient A’s out-of-pocket costs were based on an inaccurate, artificially inflated number created by the PBM. In this instance, the PBM and Part D Plan Sponsor effectively shifted $308.38 of costs from the plan sponsor to the Medicare beneficiary for this one drug. It is important to note that although this is an individual example of the incurred financial harm of one Medicare beneficiary, this cost shifting is happening on all claims in select networks resulting in huge additional profits for the plans (often wholly owned subsidiaries of the PBM’s that created the fees), and causing in widespread beneficiary impact and harm.

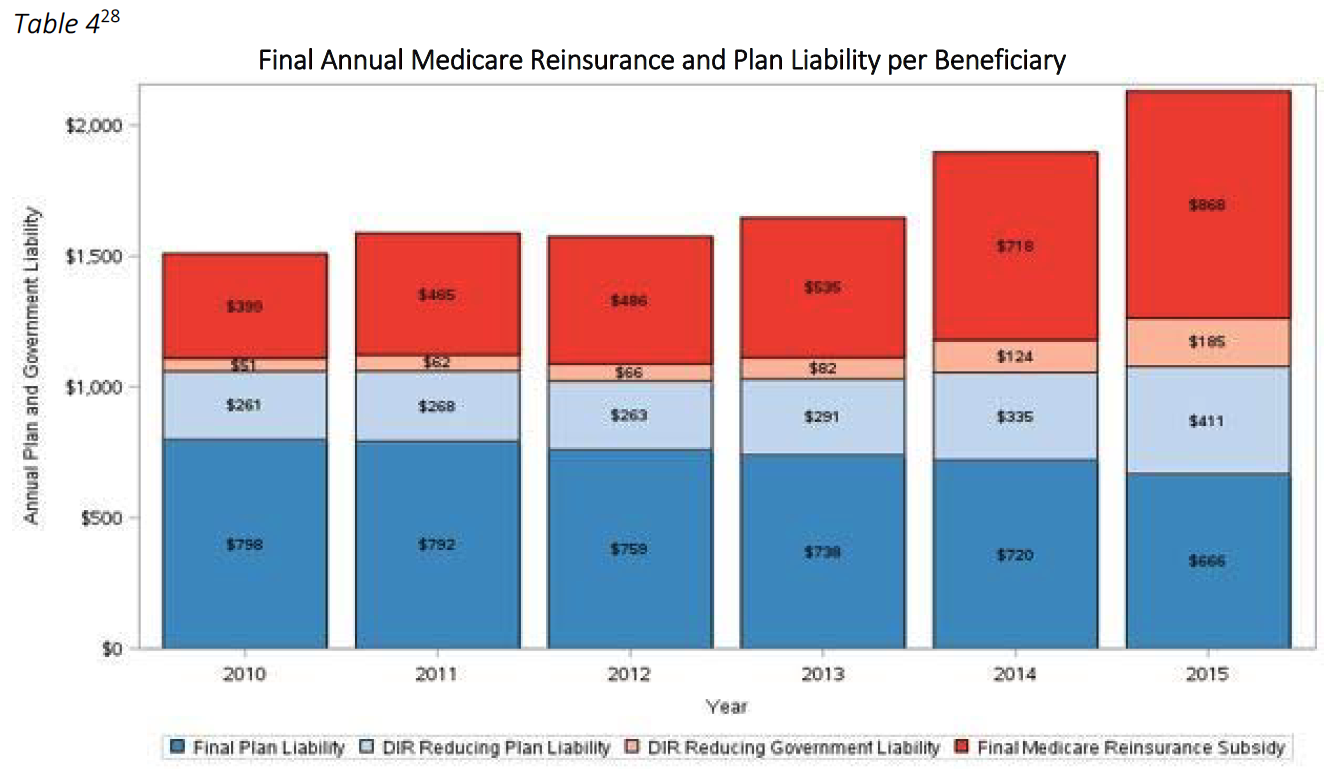

Unfortunately, this shifting of financial liability does not end here. Because the Medicare Part D Program provides reinsurance payments for catastrophic coverage costs exceeding $4,950, Part D Plan Sponsors effectively also shift costs from the Part D Plan to the Medicare Program, and ultimately the taxpayer, through these inflated point-of-sale prices. In that same example as above, with 12 fills of Drug Y at an adjudicated cost of $11,170.90, the Medicare catastrophic coverage would ultimately kick in, and Medicare would pay a total of $101,037.74 for this patient. However, if the assessment of the 4.6% DIR Fee had been applied at the point-of-sale, Medicare would have only been responsible to pay $96,105.03. In this instance, the DIR Fee resulted in an overpayment by the Government of $4,932.71 for this one patient, for this one drug. This serious impact on the Government and the patient is illustrated in Table 3 below.

The impact DIR Fees have on Medicare beneficiary coverage is evident. In fact, in a Fact Sheet issued on January 19, 2017, CMS opined on the effects of DIR Fees, and noted that DIR Fees “[do] not reduce the cost of drugs for beneficiaries at the point-of-sale.” Moreover, it is critical to note that DIR Fees do not simply result in beneficiaries prematurely entering the donut hole or paying an artificially higher amount of cost-share, but they negatively impact beneficiary adherence to prescription drug treatments and likely increase overall Medicare costs, which include also the health benefit in addition to the drug benefit. Indeed, it is estimated that more than 25% of all Part D beneficiaries that fall into the donut hole will discontinue adherence to their prescription drug regiments. Discontinued patient adherence results in Medicare having to spend more money to remediate poor clinical outcomes, including expensive hospital readmissions.

Is the Money Really Returned?

In recent public communications, several PBMs and their representatives have claimed that DIR Fees do not increase the costs to the Medicare program, claiming that DIR Fees are passed back to Part D Plan Sponsors, and that all DIR Fees are “reported” to CMS. But what does that really mean?

Let’s start with the first point: DIR Fees are passed back to Part D Plan Sponsors. In order to understand the significance of this statement, it is necessary to understand the Medicare Part D Plan Sponsor framework. Part D Plan Sponsors create and fund Part D plans, often taking on insurance risk. Four of the largest Part D Plan Sponsors include: UnitedHealth Group, Humana, SilverScript (CVS Health), and Express Scripts. Each of these Plan Sponsors owns, is owned by or is affiliated with its own PBM.

So while they may pass a portion of DIR Fees back to the Part D Plan Sponsors (less any DIR Fees reclassified as administrative expense by the PBM), it is more often than not tantamount to the PBM taking money out of one pocket (the PBM) and passing it to its other pocket (the wholly‐owned Plan Sponsor).

Moreover, nowhere in these Press Releases do PBMs state that they return the money to Medicare. Rather, they are always cautious to state that DIR Fees are “reported” to CMS. This is an important distinction, because many times, it results in no financial difference whatsoever to the amounts that CMS or beneficiaries ultimately pay for the medications based on the high upfront costs. While Part D Plan bids are “reconciled” once a year in the beginning of the June following the conclusion of the plan year, Plans are not required to pass back – dollar‐for‐dollar – any overpayments they received from the government. Rather, if it turns out that the bid as submitted was too high based on the net costs as lowered by retroactive DIR Fees, Plans are only required to reimburse any monies to CMS if there is more than a 5% deviation from the bid and actual costs. Even then, the amounts the Plan is required to reimburse are not dollar‐for‐dollar. Rather, Plans are only required to return a percentage of the excess profits realized under the bid as reconciled. PBMs and Plans at times have the ability to lower these numbers further, by allocating certain amounts of DIR Fees to administrative expenses. In either event, none of these excess profits between the increased upfront drug costs, and net costs as lowered by DIR Fees are passed back to patients, who have been forced to pay higher out of pocket amounts. Nor has it been proven that beneficiaries ultimately realize lower plan premiums, as these lower net plan costs generally only impact bid submissions and premium calculations for the following plan year, leaving patients with no immediate relief from being overcharged.

These concepts were borne out in a recent CMS report which noted that higher levels of DIR also have resulted in continually higher net costs to the Medicare program, and “ease the financial burden borne by Part D plans essentially by shifting costs to the catastrophic phase of the benefit, where plan liability is limited.”

Thus, while monies may be passed along to Part D Plan Sponsors, and even “reported” to CMS, there is no evidence that DIR Fees serve to lower overall costs to the Medicare Part D Program or to Medicare patients.

Where Do We Stand?

Increased media and industry attention in DIR Fees has begun to expose the truly egregious impact such fees have had on Specialty Pharmacies participating in Medicare Part D, as well as Medicare beneficiaries and the program as a whole. However, increased attention alone has not had the effect of curtailing the assessment of DIR Fees. DIR Fees remain an existential crisis for Specialty Pharmacies and their ability to deliver the patient care services associated with drug dispensing to Medicare Part D program participants as well as patients with serious medical conditions throughout the United States. Continued delay and inaction only serves to paint the outlook for Specialty Pharmacies and their ability to maintain their current level of engagement with the Medicare Part D program bleaker with each passing day.

Importantly though, various groups, organizations, and key stakeholders have begun to take notice of the flagrance of DIR Fees and their disproportionate impact in certain pharmacy spaces. In response to pressure from pharmacy organizations, CMS made several strides towards clarifying the adjudication in reimbursement structure, including through its January 10, 2014 Proposed Rules set forth in Vol. 79, No. 7 of the Federal Register and its May and September 2014 draft guidances. In May 2014, CMS first attempted to address DIR Fees by revising the definition of “negotiated price.” CMS noted that a Part D plan sponsor’s “negotiated price” is the amount that a Specialty Pharmacy actually receives and retains as payment in connection with a Part D claim. CMS was concerned that pricing in bidding and cost reporting across the Part D program had the potential to be inconsistent, as some Part D plan sponsors reported DIR Fees as price concessions and others reported DIR Fees as DIR. Specifically, CMS stated that it had learned that some Part D sponsors have been reporting costs and price concessions to CMS in different ways, and that such reporting differential could affect beneficiary cost sharing, CMS payments to plans, and Medicare catastrophic coverage. CMS also noted that differential treatment of costs could also affect plan bids, and suggested that when Part D sponsors and their intermediaries elect to take some price concessions from pharmacies in forms other than the negotiated price and report them outside the PDE (say, in the context of DIR), “the increased negotiated prices generally shift costs to the beneficiary, the government and taxpayer.” As noted below, this premonition has since come true, as evidenced by CMS’s January 17, 2017 report on the impact of the expansion of DIR Fees and Medicare/beneficiary liability for cost sharing amounts.

CMS attempted to safeguard against this reality by seeking to revise the definition of “negotiated price” to include “all price concessions, except those…that cannot be reasonably determined at the point of sale.” CMS released draft guidance on September 29, 2014, which made clear that a broad, inclusive standard should be applied to the “reasonably determined at the point of sale” standard, and indicated that any price concession that could be reasonably approximated at the point-of-sale should not be included as DIR, but rather part of the Part D plan sponsor’s “negotiated price.” CMS seemed to be cognizant of performance metric DIR Fees, and specifically opined that a basic rate to a Specialty Pharmacy at the point-of-sale, with subsequent enhanced payment rates based on performance in enumerated categories is considered a price concession that could be reasonably determined at the point-of-sale, and should therefore be reported at the pointof-sale.

In addition to these past efforts at clarifying the PBMs’ obligation with respect to fair and clearly established negotiated prices for Part D providers, CMS has also independently taken note of the substantial negative impact that DIR Fees have had on the financial responsibilities of Medicare beneficiaries and the Medicare program. In a Fact Sheet issued by CMS on January 19, 2017, CMS noted the steady but substantial growth of point-of-sale drug costs, combined with rapid increases in DIR. CMS noted that these trends contributed to higher upfront drug costs, which CMS found placed more of the burden on beneficiary cost-sharing, noting that “Medicare’s costs for these beneficiaries also grow. Higher beneficiary cost-sharing also results in the quicker progression of Part D enrollees through the Part D drug benefit phases and potentially leads to higher costs in the catastrophic phase, where Medicare liability is generally around 80 percent.” Thus, as concluded by CMS, DIR Fees not only increase upfront drug costs and, in turn, beneficiary copayment responsibility, but also result in increased Federal government spending on catastrophic coverage, once initial coverage and the “donut hole” have been satisfied.

CMS was not alone in these observations concerning Medicare and its beneficiaries. As time progressed, more and more organizations and stakeholders began to question and challenge the legitimacy, reasonableness, and legality of PBM-imposed performance-based DIR Fees. The National Community Pharmacy Association (“NCPA”), National Association of Specialty Pharmacy (“NASP”), Community Oncology Alliance (“COA”), and AmerisourceBergen have all voiced serious concerns about the appropriateness of such DIR Fees, with COA having commissioned an extensive White Paper analyzing the lawfulness of DIR Fees and how PBMs were utilizing them to increase their profits at the expense of taxpayers and providers. Overall opposition to DIR Fees has garnered wide support across stakeholders in the healthcare industry as 99 organizations joined in a letter supporting Federal legislation aimed at prohibiting DIR Fees.

Recognizing the seriousness of DIR Fees, several Senators and Representatives introduced Federal legislation aimed at curbing retrospective DIR Fees. The “Improving Transparency and Accuracy in Medicare Part D Spending Act” (H.R. 1038 / S. 413) aims to prohibit the use of retroactive DIR Fees by Medicare Part D plan sponsors and PBMs. The proposed legislation would amend the Social Security Act by adding a section entitled “Prohibiting Retroactive Reductions in Payments on Clean Claims.” The proposed legislation would effectively prohibit Part D plan sponsors and their agents (such as PBMs) from retroactively reducing payment on clean claims altogether – essentially seeking to do away with after-the-fact PBM claw backs under the guise of DIR Fees. This bill had originally been introduced in the 114th Congress in September 2016 but has since been re-introduced in the 115th Congress on February 14, 2017.

Unfortunately, the recent publicity and notoriety of DIR Fees has also resulted in the PBM industry quickly grabbing their swords to defend DIR Fee programs. In ways not unlike the former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals – Martin Shkreli – attempted to defend his company’s 13,000% price hike, so too did the PBM lobby and the CEOs of major PBMs seek to defend the murky and secretive fees. Facing questions from Wall Street analysts about their DIR Fee programs, many PBMs were quick and direct in their efforts to defend and justify the programs in press releases and during earnings calls.

On February 2, 2017, in a swiftly drafted Press Release, CVS Health (NYSE: CVS) responded to questions regarding the lawfulness of DIR Fees just three days before its quarterly earnings. In the Press Release, CVS Health only indicated that a change in the DIR Fee “would not be material to our profitability,” and stated that such DIR Fees “are allowed under CMS regulation, and are fully disclosed as part of the annual bid process.” During CVS Health’s Fourth Quarter 2016 earnings call on February 9, 2017, its CEO also touched on DIR Fees as the very first issue after reporting basic earning numbers. CVS Health attempted to categorize the existing reporting and comment on DIR Fees as false and misleading, yet CVS Health parsed words in discussing its DIR Fee – or “Performance Network” – program. CVS Health claimed that DIR Fees are utilized to reduce the net cost of the Medicare Part D program, stating that such DIR Fees are “fully passed through from the PBM to its clients [i.e., Part D Plan Sponsors].” What CVS Health failed to mentioned, however, is that its single largest “client” in the Medicare Part D space is SilverScript, a wholly-owned subsidiary of CVS Health. As noted above, this is tantamount to simply moving money from one pocket (i.e., from its PBM arm, CVS Caremark) to another pocket (i.e., to its plan sponsor, SilverScript). Importantly, in its investor presentation, CVS Health stated “CVS Caremark [the company’s PBM subsidiary] does not keep or profit from performance network-based DIR.” The company did not say that CVS Health – the publicly-traded parent corporation – did not benefit from the DIR Fees it extracts from Specialty Pharmacies.

During Express Scripts Holding’s (NYSE: ESRX) Fourth Quarter 2016 earnings call on February 2, 2017, its CEO dismissively concluded that DIR Fees were agreed to by retail pharmacies and have no impact on the PBM. The CEO made no mention of the inappropriate impact on Specialty Pharmacies, and instead, alleged that DIR Fees helped to drive down costs by being passed back to plan sponsors and “reported” to CMS. Express Scripts similarly failed to mention that it too owns a large Medicare Part D plan, Express Scripts Medicare, the exact entity that receives DIR Fees. With little options or room for negotiation or bargaining power, independent pharmacies are often left with no choice but to accept one-sided PBM contracts with ambiguous and unclear terms, which are in turn, used by PBMs to their advantage, at the expense of Specialty Pharmacies, as well as patients and the Federal government.

Of extreme importance in all of these PBM communications, other than a flippant and offthe-cuff remark by CVS Health’s Executive Vice President in response to a question from an analyst, is that nowhere do the PBMs state that any of the monies recouped through DIR Fees actually get passed back to the Government. Again, they are all careful to state that the monies are passed back to the Part D Plan Sponsors, but never state that the monies are actually turned over to Medicare. Instead, they use specific language, stating that the DIR Fees are in some capacity “reported” to Medicare. Importantly, even to the extent that these fees are even reported to Medicare, as noted above, it does not mean that they are passed back to the government.